I think there's something to Roger Ebert's contention that video games are not art, which he seems to have stammered out like an uncomprehending seer. And there's something amusing about the Singapore salesman who helped to swindle the public of millions of dollars for a wealthy family. Both may have something similar in mind. Both of them provoke this thought: How do we value something subjective?

The value of art is subjective because its purpose is, ultimately, that of subjective expression. And subjective expression is all that is directly relevant to the artistic process. No matter what other motivations exist in the artist's head, which purpose the artwork ends up incarnating is what we appreciate—and in art we appreciate the purpose of subjective expression.

Perhaps we need an example to illustrate this point more vividly. Think of the Pagliacci paradigm. At any moment during a performer's performance, he may have a number of motivations. He may be performing to get the performance over and done with so he could go home. Or perhaps he is performing with a conscious desire to earn some money to feed his family. But these motivations are irrelevant to his art, and if he betrays them his performance would suffer. In the theatre, the purpose that we want to apprehend in a performer's act is that of expressing the character he is playing. And so it is with all art.

If the artistic process requires subjectivity, it is opposed by the objective. Objective ideas external to the individual pollute the artistry of an object that is intended to be an artwork. Imagine an artist who has a marketing team that gives their input to the creative process based on what they expect would sell in the market. We would find the artist engaged in a process that is less about artistic creation and more about product design. That is why video games tend to be far from being purely artistic—the commercial aspect permeates and corrupts the creative process.

For that matter, artworks that are created to be sold in the marketplace might face the same problem. After all, we can see the difference between a true work of art and a souvenir. The latter is more about craft, created as a pretty or impressive thing specifically to be sold for a sum of money. Thus, if the creator is clearly motivated to create something that has objective value, especially in monetary terms, the art becomes suspect. By this reasoning, amateur art is hence the most secure in terms of its artistry—we are most assured of its subjective quality, its brilliance notwithstanding.

We can see, therefore, a crucial difference between the work of man and the work of genius. Why, then, are we so keen on translating everything into the former?

Once we try to put an objective value to the subjective, we turn something that is incommensurably valuable into something of bounded value. And, at the same time, we enter into the realm of absurdity. As the charlatan of a salesman said, "How I value my history and heritage will be different from the way you value it"—hence his valuation of a museum contribution at fifteen million dollars while 'expert' valuations put it at less than two million. We start arguing and imposing arbitrary terms.

The result is a patently uninteresting universe. Our own imagination has filled our world with numbers and robbed us of the kind of imagination that paints it with colour. No wonder boredom is the modern affliction.

Why, seeing this, do we not complete it by fully converting the spiritual into worldly terms? Shouldn't we ask, "What price divinity?"

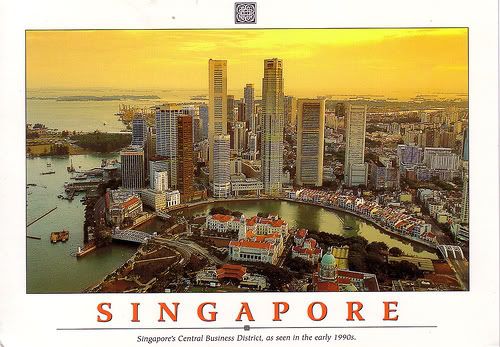

But perhaps we have—nature gave the pagans their gods; men in suits give us ours. On postcards there is the picture of an island of offices on a well-oiled sea. And to such a creature we yield our sacrifices. Our love's labour.

An unpessimistic pessimism

Posted by

moses

@

20:56

•

life,

optimism,

pessimism,

philosophy

•

0

comments

![]()

What has kept me going with a smile is philosophy.

In the face of the unknown, I find joy in discovering that the absurd man might be superman or overman. Vanity? No, reality.

And, in a way, I find myself agreeing the Hegelian sentiment here—while religion might have been the opium, philosophy offers the vision.

Let me explain what I mean. It begins like a story, "zeer-e gonbad'e kabood", or under the dark sky, as the Persian Shia tradition goes. One day, we wake up to discover that the world is an impersonal place. We find that it is unfamiliar to our reason and hostile to our plans. This is the moment of the absurd, as Camus describes it, the moment when we realise that our selves are subject to a universe whose laws are indifferent to our thoughts. We know then an irresistible force, but it isn't a living one; it does not know us. "Yeki-bood; yeki-nabood"—there was one, and there was no one.

But let us break away from lyricism. While Habermas, perhaps echoing Kierkegaard but from a less fatalistic perspective, says that secular reason is somewhat lost and "unenlightened about itself", Camus contends that the absurd man lives with the imperfection of reason and does not leap into what he considers the irrational—blind faith, or the obliteration of reason. The former, however, would reply that the banner of reason has only led, ironically, to a naive faith in science.

It's hard to say who's right. Yet I think Habermas has merely arrived at epistemic circularity, the practical fact that we need faith in our basic ways of perceiving and reasoning to make any sense of the world; he is probably also saying that reason doesn't tell us why we should have faith in those. And the absurd is more than admitting and living with these 'deficiencies'. It is the knowledge that what matters to each of us most in this world, the subjective self, does not square with the objective world.

This is the reality that I was talking about, a reality where the subjective individual is alienated and dominated by the objective. We live in a world that is, in truth, very far from enlightenment; and this gulf will remain as long as we live or die by the grace of money.

That is the reality that needs lyricism. But, above all, it needs thought.

And so we tune in again. Julian Young writes in Nietzsche's Philosophy of Art that nausea, the reaction to the absurd existence, is almost a dignified condition. Down this path, he sees Nietzsche's overman as the world-affirming man, one who is willing to go through each and every experience in his life over and over, who regrets nothing. "Yes", the overman says, "the world is a hostile place—and so what?"

Is the overman, then, the absurd man? Have we been looking at the man in the red cape and never thought to look at any person that we might pass by in the street?

This perhaps is key: in the affirming of a harsh reality, the subjective self reveals its strength and is affirmed. While in the most agonising moments, we like critical patients might need some morphine to go on, it would not solve the problem of existence. In times, I imagine, when even your faith abandons you, you choose to live or die; and in choosing the former, what we always know as the human spirit refuses to submit itself to be obliterated.

The lyricism and the introspection, then, are not vanities. They remind us of the problem of existence. They might be our lifeblood when we lie wounded.

And in the spirit of storytelling and reflection, I've realised something else: the mourning Mother Courage, the mother of slain children who is able to stop clinging to her wares to go on is the tragic heroine of the working class.

In the end, revolutionaries might be the sons of a better age, but they should not forget themselves—lest they forget to pass over a petty careless existence.

When it comes to faith, I doubt.

But it doesn't stop there. Yes, we do have reasonable beliefs; religious faith too can be reasonable. In fact, if epistemic circularity is unavoidable, then every aspect of our life involves some kind of faith.

Still, this doesn't mean we shouldn't doubt our beliefs. More precisely, we should doubt our understanding of the world from which our beliefs arise.

Invariably, there are times when I doubt what I know, doubt that I can be certain about anything but the simplest things. During those times, like the experience the eponymous philosopher of the Bible describes, the good things in life just don't feel as good. Without certainty, one becomes anxious.

Fortunately, I find that the anxiety soon passes, and what I have instead is a refreshing sense of peace. It's a feeling that is akin to floating along a flowing river rather than struggling and going under—it's something that you could only feel if you're willing to ease up on the struggle to maintain certainty.

Indeed, I think perpetual anxiety is our lot if we are so desperate to remain certain. Or, if we never admit it, we would merely be living in an illusory shell. Faith requires lies in order to exist freely and indefinitely without doubt creeping in. And doubt that is not embraced, that is not allowed to come into opposition with our certainties, can only give us anxiety.

Openness of mind, then, is the only real cure to the discomfort that doubt brings.

To be sure, as physical beings, we have physical needs that give rise to a need for some physical and material security. And I think this is a legitimate general need, the satisfaction of which is a worthwhile social goal—hence my support for socialism.

Beyond a certain albeit (granting the possibility that specific needs are subject to change) non-specific point, however, we should probably be more comfortable with uncertainty. And in learning and thinking, we could achieve this by having an open mind, a disposition that does not hold on too tightly to the certainties that we think our understanding gives us.

I suspect that we have been conditioned to loathe uncertainty in most aspects of life. We need to know, we want predictions and projections. Living in society has taught us that this is the way to live. It has become like an instinct, something that drives us mechanically.

And instead of living, in a richer sense of the word, we are letting our shoddily-constructed faiths and mice-and-men plans dictate our lives. I think we become something less than what we could be.

And instead of living, in a richer sense of the word, we are letting our shoddily-constructed faiths and mice-and-men plans dictate our lives. I think we become something less than what we could be.

It seems apt, therefore, to quote the words that Nietzsche put in Zarathustra's mouth:

Man is a rope, tied between beast and overman—a rope over an abyss... What is great in man is that he is a bridge and not an end: what can be loved in man is that he is an overture and a going under. I love those who do not know how to live, for they are those who cross over.

Only doubt is certain; what we do know is that we might not know. And that might not be a bad thing. For one, it might give us a key to overcoming our petty troubles.

Essays on mind and matter I

Posted by

moses

@

10:53

•

life,

optimism,

pessimism,

philosophy

•

0

comments

![]()

As you get older, you tend to find yourself looking back more and more.

When you're young, chances are you couldn't wait to grow up because you wanted to do things you couldn't do as a child. But as we get older, I think many of us find that we want to go back, half-wishing that somehow we could reverse time, perhaps dreaming that we could change some things about the past.

Is life doomed to be full of nostalgia and regret?

Well, I think nostalgia can be a kind of recreation, so it's not really a bad thing. Regret, however, is much more difficult to judge. I won't say that we should never have regrets, because some things are worth regretting—without the prospect of regret, we might do things that we would do well to regret later. But is it worthwhile to live a life full of regrets?

As I reflect on it, it becomes more apparent how different and perhaps incommensurate with others' every individual's experiences are. You would think that people with broadly similar circumstances would have broadly similar experiences, but that's not necessarily true at all. While today's mainstream philosophy often regards experience as very much an internal thing—experience is intangibly subjective and thus it is impossible for one person to fully apprehend another's experiences—most people still intuitively think of it as an external thing—there is a real world that we are obviously interacting with and is therefore what determines our experiences.

I think the truth is somewhere in between (or a configuration of both?). How you felt, thought and acted are determined both by your circumstances and how you perceived them. The past is like this or that because you are partly responsible for making it the way it is, not just through your externally-oriented decisions but also through an internally-oriented one—how you chose to see and internalise your circumstances at that time.

Indeed, how you perceive the past is also a choice. However, there is a relatively inflexible element to memory in that it is to a large extent determined by past decisions you made, which are unchangeable. If you saw your days as miserable, you're likely remember them as miserable today whether you want to or not because the decision has been made in the past to perceive and thus remember them that way.

How you feel about the past is perhaps more of a choice. But, by extension, you're still relatively unfree to choose since the memory that you are reacting to is, as I mentioned above, inflexible even in the internal (self-determined) sense. Therefore, I think regret is often an unavoidable feeling.

What can certainly be helped and what really matters is your decisions on the present and, to some extent, on the future. And as I mentioned on New Year's eve, past experiences can help by informing these decisions. So you may regret things in the past, but don't let the mistakes you regret bleed into the present, either by persisting or by negatively affecting your ability to choose how you live your life today.

Thus, the past may be there to be wept over and the future may be there to worry about, but the present is here to be lived and enjoyed.

As we get older, I think we would do well to keep that in mind.

For a eudaimonic society

Posted by

moses

@

03:20

•

ethics,

eudaimonia,

philosophy,

politics,

Singapore,

socialism

•

0

comments

![]()

What does it mean to live the good life?

That is Aristotle's question. It's also one that we would do well to think about in this day and age. Does it merely translate to pleasure-seeking, a vulgarised Epicurean way of life, or a crude Utilitarian one based on the consumption of material goods? Looking at how many people view life and its rewards today, those do seem to be very popular views.

Well, I won't be preaching about the good life here. I will merely borrow Aristotle's concept of the eudaimon life—meaning a fulfilling or flourishing life—because I think it's very appealing. Basically, it's a life in which one seeks to realise one's potential as fully as possible.

What I will instead talk about is how the eudaimon life figures in politics. After all, a coherent ethical system has to integrate the private with the public or the individual with the social and political.

I think it's a great weakness of the modern (and here I mean liberal) political system that it doesn't tackle this question. At most, it only goes as far as to praise freedom or autonomy and encourage the means that are necessary to ensure it, such as political participation. Of course, governments often do promote the concepts of a harmonious society, healthy living and etcetera, but these are a matter of policy rather than integral aspects of a coherent philosophy.

The problem comes where, instead of enabling a pluralism of perspectives that the prizing of autonomy warrants, modern political philosophy merely ends up looking away while a dominant ideology monopolises the people's consciousness.

And that ideology can do so because people have material needs, which it has been able to dictate, both through their provision and through the creation of new ones. In other words, with a pervasive market system based on the valuation of most aspects of life through currency, it has been able to dictate people's way of life. It has also been able to create a false consciousness, which I take to mean the creation of endless wants and needs that it and only it can fulfil.

It's no wonder that many view life as a long road of hard (or not so hard) work that promises to reward them with comforts and luxury. And in such a society, money (and I don't mean just hard currency), as the universal medium, becomes paramount. Everyone becomes, often involuntarily, money-minded.

That is quite contrary to the eudaimon life. What the latter seeks is not material wealth, but wealth of character and being. It teaches moderation and encourages the pursuit of excellence. It seeks a balance between the material, social and spiritual.

But only if people are released from the shackles of material domination and false consciousness would they be truly free to pursue such a way of life.

And this is why I think the eudaimon life is related to and forms a moral structure for a socialist society. Far from being an egalitarian hell, socialism seeks to collapse the structures of material domination, to put the fruits of labour in the hands of those who laboured for them so that they may live their lives to the full. It does not stand for authoritarianism and collectivism. It stands for freedom in more aspects life than just the political.

Now, on a final note, does a political philosophy that seeks the fulfilling of one's potential imply support for a meritocratic system? This is something that needs more time to be considered. But if I were to hazard a guess I'd say no, in the sense that if meritocracy gives license for material domination by the meritorious, then it would be contrary to the spirit of a eudaimonic society.

Besides, we need to be careful when we talk about meritocracy. Without a level playing field and true quality of opportunity, true meritocracy is not possible. We need to distinguish between true and idealistic meritocracy and pragmatic meritocracy, the latter which Singapore (for example) subscribes to. Which do we mean?

Pragmatic meritocracy does not make a clear distinction between those who have the odds stacked against them and those who were born lucky. And our sense of fairness, which is apparently corroborated by neuroscientific evidence, should prevent us from buying into it.

Missing the forest, or how experts can be dumb

Posted by

moses

@

12:09

•

philosophy,

Singapore,

society,

Today

•

0

comments

![]()

If there is something wrong with the method of inquiry that analytical philosophy is partly guilty of, it would be the fragmentary way in which reality is examined. Each field or subject tends to be seen independently, frequently leading to big-picture incoherence.

Moreover, there is often (in less straightforwardly philosophical fields) a tendency towards a strictly realist method, focusing almost entirely on the empirical and taking revealed reality as the only plausible element in discussion. This again leads to incoherence, even where the subject is labelled as 'comparative'.

Now, (on a somewhat ironic note) all this might sound rather abstract and hence obscure. Well, I'll cut to the chase and speak from an example. After all, the empirical does have a substantiating role.

I read, with a measure of bemusement mixed with ruefulness, the 'expert' analyses on the recent trend of casino-themed toys becoming popular in Singapore.

In response to public concern, a few psychologists quoted by Today downplayed the significance of this trend. One compared it to the availability of "toy guns which encourage kids to play shooting and killing games", stating that "it is up to parents to decide what they want for their children".

At first glance, that's a pretty good comparison. Certainly, we can agree that casino-related toys becoming popular does not mean more children will grow up to be compulsive or reckless gamblers, as much as legalising homosexuality does not mean more people will become homosexuals.

However, in this case, that argument is only good as long as it stands alone. I suppose this is where psychologists who examine the individual removed from his/her social context should retire to the backbenches.

Had the toys become popular years ago, those experts would be completely right. But what makes this trend worrying is not some unfounded fear about the toys. Rather, it's the fact that it comes in the wake of the opening of the casino and all the hype that surrounds it. Hence, it's not a question of psychological effect alone; it's also a question of cultural trends.

What is worrisome, therefore, is not that the toys could exert some insidious influence on kids, but that the culture celebrating extravagance could. The toys are merely a vivid manifestation of that culture, a sign of how far down it has crept and become positioned to affect the people's psyche.

Businesses thrive on exploiting opportunities, and social trends generate the latter. Parents don't buy casino-themed toys to teach their kids "the concepts of chance and risk playing" and "the consequences of incurring debt", as one psychologist puts it glibly. After all, as the expert noted herself, more conventional games such as Monopoly could serve that purpose. Parents buy casino-themed toys now because they buy into the hype, one that is reminiscent of Wall Street's extravagantly reckless culture. That's not exactly the best thing to aspire towards, is it?

I think this is one of the instances where science, steeped in its own arcane knowledge, becomes negligent. Reason and science are not synonymous. I've written favourably about scientists (including psychologists), but I have to say that putting your faith in just any form of scientific inquiry isn't prudent either.

Here, I say that it is almost a crime to talk only about trees.

Why we are a passive-aggressive society

Posted by

moses

@

20:10

•

politics,

Singapore,

society

•

0

comments

![]()

I'm not the only one amongst the people I know to have opined that Singaporeans are easily offended. I'm also not the only one to have been on the receiving end of their knife-in-the-dark kind of wrath. Nor am I the only person to have been frustrated trying to work something out with them, whether it's a project or just a get-together, and failing due to their lack of commitment, only to have them play victim in the aftermath. At the same time, we quite frequently observe farcical outbursts and quarrels amongst strangers in the street.

All this seems to be a curious mixture. Actually, this bubbling cauldron may be a regular feature amongst urban populations living in high-stress environments. But I think there's a special dimension to this amongst Singaporeans, so let me offer a uniquely Singaporean analysis of how I think this condition comes to be.

I think by now you're not a stranger to the fact that Singapore is an authoritarian society. Dissent faces disapproval at best and sometimes even open persecution. Certainly, it's not very difficult to be obfuscatory about this in legal language. But, when it comes down to it, Singaporeans who care to defend the system would defend it on the basis that that's how things are done over there and that it works.

But we're not exactly interested in the politics of the country now. I'm going to talk about how that translates into the people's behaviour.

And not only is dissent not politically tolerated, there is a consciousness that, as a multicultural society, speech needs to be regulated. Besides the prevalence of censorship backed by the legal stick (as three guys found out recently), I think the indoctrination is so successful that people actively censor themselves from openly saying things that might provoke conflict.

Added to the mixture is a twist of Asian reserve, engendering a dislike for confrontation. The result is a people who tend to be 'quietly' unhappy. Resolving problems with open, honest communication is frequently eschewed for fear of unpleasant emotional encounters. After all, the latter are not the kind of stuff responsible members of the community should engage in.

Hence, we tend to bottle our feelings up, letting them out only behind the backs of the people with whom we are unhappy. But that's not enough sometimes. With all the pressure we are under, we might really need to let off steam. So we take it out on strangers, people that we don't have to see every day and don't have a personal relationship with—bus drivers, public servants, salespeople and etcetera. Hence the quarrels in the street.

Moreover, in such a competitive and authoritarian environment, where the stick is ready to hit and people are ever ready to take your place should you slip, we hate to be wrong. Out of concern for our own good, we will try to push the blame or at least minimise our culpability. In fact, we often want to seem to be the victims because, otherwise, the responsibility is too heavy to bear. Or we might be confronted by angry people.

And when people dare suggest that we are wrong, we bring our personal indignation to bear—we quickly feel offended.

All these symptoms seem to be the hallmarks of passive-aggressive behaviour. And I think that's what we are, a bunch of passive-aggressives. We are also irresponsible since we loathe the full implications of responsibility.

I firmly believe that politics shape the way we live. So I do wonder if the latter is surprising in light of the fact that we're not given the responsibility of political choice.

Simply put, the government thinks we are children and we let that pass. And so we are.