Showing posts with label art. Show all posts

Showing posts with label art. Show all posts

I walk with the wind against my face, blowing frigid and fierce, promising a cold day ahead. This is of course typical of the repertoire of autumn weather in London: wind, rain and fog–and they have all made an appearance throughout the week.

Entering the Barbican Centre, I hurriedly join a friend in the queue that has steadily been building up even before the Rain Room opens. The sight of the growing line begs the question: Why would people want to visit an installation about rain when they experience rain all the time in this city?

Over an hour later, finally stepping inside, the darkened space that is the Curve Gallery feels warm enough–the first difference between experiencing rain in here and experiencing it outside during this season. But the biggest and most important difference between the two experiences is the magic of the installation itself: unlike in the outside world, walking under the rain in here will not get you wet.

There are, however, a few conditions. Firstly, you must take your steps slowly to allow your position to be properly detected. Secondly, anything extending too far from your body is not protected–stretch your arms out far enough and they will get wet.

These caveats hint at the inner technical workings behind the Rain Room's magic; and they may perhaps take a little of the sense of wonder away.

Still, waiting just outside the torrential box, the excitement is palpable. There is something about the field blanketed in drops of water, glinting in the harsh white light that shines across the space, that is fascinating; and, chances are, you feel more than ready to give it a try.

Our turn comes and we step into the rain zone carefully, a dry space forming around us. Looking up, I can see circles where the downpour has been stopped above me, and they seem a little wide, perhaps slightly too wide for the experience to be as thrilling as I imagined.

Nonetheless, the curtain of rain around me, appearing misty in the light that illuminates it, seems as though it encloses me in a kind of surreal personal sanctum, surrounded by a persistent yet ephemeral shroud. And the experience is sublime. The world outside one's immediate vicinity seems further away but still eminently reachable–it's as though one has withdrawn tentatively into a serene and reflective place, a mandala, observing the world, samsara, from a mediated distance. It reminds me of the many times I have stood under an umbrella in tropical rain, the water mere inches from my body all around; except that here I can remain completely dry.

And that seems key to the installation's appeal. Rain in the outside world often presents itself as an obstacle, an inconvenience, a source of discomfort; in here, one is free to experience and contemplate rain without having to relate it to one's immediate needs and desires. It is the quintessential Schopenhauerian aesthetic experience.

And that is why to me, despite its rather technical and not quite wondrous nature (partly due its technical limitations), the Rain Room is art. You can't quite get the same experience anywhere else.

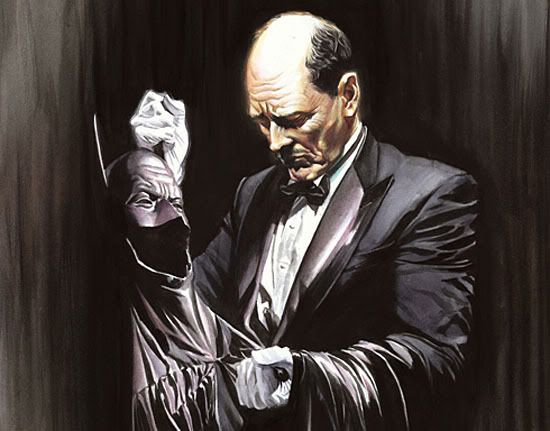

Don't bet on the Batman

Posted by

moses

@

16:37

•

art,

culture,

film,

heroes,

media,

psychology,

society

•

0

comments

![]()

Upon hearing that a massacre had occurred during a premiere of the latest iteration of the Batman films, some people asked, "Where was Batman?"

Perhaps the joke, all jokes are not an appropriate response to such a tragedy. But this is also a singularly powerful question. Indeed, where was—is—Batman?

Of course. He's not real. Batman is fiction. Everyone except some kids (and maybe some delusional fools) knows that. People can be expected to know the difference between reality and the superhero fiction, can't they? Well, can they?

Most people know that superheroes don't exist. But to what extent do they grasp this fact? I mean, why do people like superhero stories? The modern trend in fiction may be to humanise superheroes, to depict the conflicted and flawed hero. But they're still superheroes—they are still powerful; they can still solve the world's problems, even if they must bleed and sacrifice much in the process. Perhaps stories like Watchmen defy this convention altogether, but not the Batman films.

Christopher Nolan's Batman is a tortured hero, a hero who has to mask himself as a villain. But the audience are well aware that he is hero. And the fantasy of the mighty superhero, furthermore, is not shattered. People can expect Batman to save the world within the big screen. They want to savour—even just a shadow of it—the excitement that springs from the knowledge that a saviour is here to fight for them. Fiction melds with reality; the story is not real, but physiological reaction to it is.

That is why the massacre is semiologically powerful—a horrible crime is occurring while the superhero is 'present' on the big screen, a demonstrably flat image that interacts with the world purely as illusion. It's not even impotent; it's nothing at all. The mirage is shattered completely by the jarring reality of a tragedy unfolding simultaneously. Thus, observers may be prompted to ask, "Where was this hero?" Of course they'd known that he doesn't exist. But this incident makes them realise that anew and takes the realisation to a higher, uncanny level.

The death of the superhero, a theme that has been explored in fiction, is not as devastating to the fantasy as the real deaths of superhero fans in front of the big screen.

However, while many of us may intuit this, not everyone will realise what it means. Take, for example, this Facebook comment about the survivors:

All I can say is send them a hero Chris send the dark knight to the hospital for them, so the children know there are real heroes out there, and that evil won't win

This is exactly the kind of sentiment that should have been extinguished by this incident. Yet people want to hold on to the fantasy and, worse, to perpetuate it by instilling the same delusion in children—the notion that there is a simple fix to the big problems that can be accomplished by a few mighty and benevolent individuals.

Perhaps adults have a vested interest in raising children who are naïve and docile. Some of them had probably been raised to be that way themselves. But the use of a crutch is symptomatic of disability—this much-needed delusion reveals people's psychological inability to steer away from a petty existence waiting for salvation.

Those people have got it the wrong way around. If they did exist, superheroes would exist because people are unable to fight for themselves. Thus, instead of wishing that they did exist, we should want their existence to be unnecessary. That, not having a superhero around, would be truly empowering.

Art and patronage has a complicated relationship. The reason is simple: Whoever pays for and facilitates the creation of art tends to influence the direction of art.

While this may be an ordinary thing in the art market, where artworks are freely hawked like any other commodity, it presents a problem for political art of the subversive kind. Art that receives state patronage is by definition art that is approved by the state; it therefore has limited subversive potential. Subversive art must hence be art that is not explicitly approved by the state; and an artistic object or act that is extra-legal is thus a good candidate for subversive art.

The arrest of the 'Sticker Lady' in Singapore and the subsequent online furore provides a good entry point for a discussion about the relationship between the state and subversive art.

From the point of view of the state, what she did was an act of vandalism or (if the distinction matters) at least that of the defacing of public property; to many, it was art. These are irreconcilable viewpoints not just because the state is not the best arbiter of what is and what is not art, which is a complex debate not suited to the dry legalist realm of discourse, but also because what she did is so compelling by virtue of the fact that it was an act of defiance of the law—in other words it spoke to its audience because it was subversive.

So, in that sense, demanding that the government recognise what she did as art and not a crime is quite beside the point. And, by extension, turning this into an issue of national policy on art and creativity is the wrong way to go about it; without a consensus that what she did was worthy of official recognition, the conversation would quickly reach a dead end. Instead, what we can do is to question the penalty against such acts and debate the implications of a harsh penalty on freedom of expression. Realistically speaking, what she did would always be legally deemed as a crime, but the enforcement of the relevant laws could certainly be toned down.

Why is a review the legal penalty for vandalism important? Firstly, a harsh penalty for vandalism is indicative of an authoritarian political culture that is not tolerant of dissenting voices, especially when this penalty is disproportionately heavy compared to penalties for other more severe crimes.

Secondly, if we want art of every kind to flourish, including subversive art, then it follows that we should try to reduce the heavy-handed prosecution of some kinds of art. Demanding that the authorities recognise subversive art is contradictory, but asking them to be less stern towards it is not.

Finally, this would also serve as a tangible and actionable goal that extends beyond this incident–a larger goal that could actually be reached without the debate being hopelessly mired in arguments about art and vandalism.

I have other topics in mind that I want to write about, but right now I'm struck by a sudden desire to recapitulate and summarise what I studied last year. Maybe it is the desire to seize something tangible before my memory of it fades. So here goes.

The main lesson I derived from the research I did for my dissertation is that any claim that film critics have as arbiters of a non-pluralistic (in both the moral and universal senses of it) notion of good taste is undermined by the idea that taste is a means of social distinction; a means of thinking of oneself as superior or different based on vague but compelling categories of identity with which one identifies.

This implies that taste is neither objective nor entirely subjective. While critics often try seductively to suggest the former, aesthetic 'laymen' tend to stress the latter. Rather, according to my research, taste should perhaps be described as 'intersubjective'. But, more precisely, it is constituted by hyperreal categories (such as socio-economic class) that often appear to us as objective categories.

In other words, from the perspective of theories of language, taste is an entirely practical concept in human language that has perhaps received far too much theoretical attention. It is very much rooted in our social structures and psychology and does not properly belong in the domain of the aesthetic.

I understand that aestheticians may want to think of (good) taste as the practical implication of what is good or beautiful in aesthetics. But I think that's just not the case in contemporary reality. Taste has much less to do with aesthetics than with social categories.

And as articulations of the social structures that give rise to this social phenomenon, the pieces of film criticism I examined do not even use the language of aesthetics, contradictory or hypocritical as it might often be. Tellingly, the critics do not seem to care to exhibit a grasp of aesthetics before presenting themselves as an authority on film tastes.

Don't give up on English to oppose it

Posted by

moses

@

11:08

•

art,

culture,

identity,

Singapore

•

0

comments

![]()

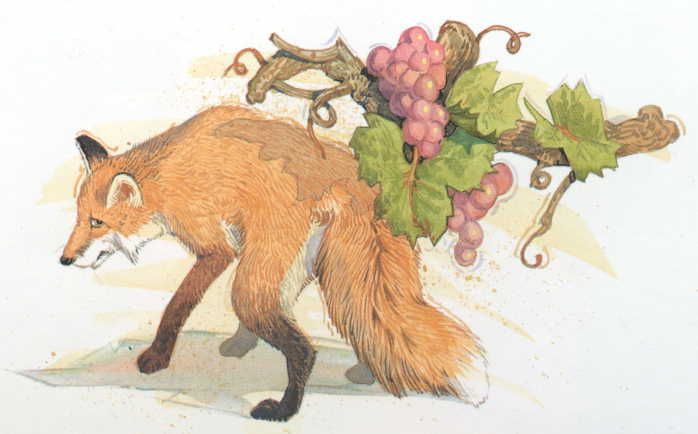

Illustration by Don Daily

As a debate plays out this weekend regarding the use of Singlish, let us recall the fable of the Fox and the Grapes. It's a story that is familiar to us, in which a fox, unable to reach some grapes, disparages them as sour grapes.

The term 'sour grapes' has come to signify envy, but there is an element of the pathetic in the fable: Unable to obtain something, the fox takes refuge his rejection of that thing.

Those who entertain thoughts of replacing English with Singlish should remember this tale. The idea of replacing English entails doing away with it altogether, and, if they have resistance in mind, that would not constitute a gesture of resistance.

Why is that so?

An act of resistance without a centre or a point to which it is opposed is untenable. While it might seem clear that communicating in Singlish can be conceived of as an act of resistance that is externally directed against the officious imposition of standard English, it would—recalling the fable—be reduced to a desperate cry if it does not arise from an internally-directed conflict.

This argument is motivated by the mirror-image of the maxim that external opposition is inevitably a reflection of internal contradiction—that a deliberate work of art must be internally coherent to project a meaningful opposition externally. The act of speaking Singlish, if it is to be a performance that mimetically mocks or deconstructs official language, must achieve this internal coherence through the act of conscious and deliberate resistance by the speaker, who has the capability to communicate in standard English and yet chooses not to do so. Without this capability and the actor's power to choose to begin with, the act loses its strength.

It seems eminently foolish to oppose centres of power by reducing what power you have to enact gestures of resistance. Even if those who are for replacing English do not intend it as an act of resistance, their position would still be tantamount to advocating the weakening of the power to resist standard English as a symbol of coercive authority. That would certainly impoverish any speak Singlish movement.

Art and its media

Posted by

moses

@

11:26

•

art,

culture,

philosophy,

politics,

society

•

0

comments

![]()

The difficulty of praxis in art is compounded by the intrusion of the empirical or the purely practical. The definition of art is a political matter; it is bound up with the power to dictate or influence what is considered art and what is not. Perhaps the philosophy of art can exist in parallel with the power structures that, in our reality, define art and the beautiful. However, one gets the feeling that praxis should still entail the reconciling of aesthetic theory with aesthetics in practice, if not overcome the latter altoghether.

The trouble for aesthetic theory is, even if it has revealed the secret of the beautiful and why art is art, it frequently does not account for the practical preoccupation with the medium as a crucial determinant of what can be considered art. A digital image is at most 'art' in a much more qualified sense than is a painting on a canvas. This is because it does not in itself (without relying on the reputation of the artist or on physical installations), by virtue of its medium, typically garner the kind of recognition as an artwork that comes with socially-bestowed value and that can provide the artist with the material means to continue his work.

A way of dealing with this reality is to call for an anti-elitist view of art that disregards or devalues the importance of the art establishment, the respected institutions that serve as gatekeepers for universally-recognised art. Such a view would not discriminate between career artists and those who are not or between one medium and another.

Yet, as suggested earlier, this conception of art would only exist in parallel with the politics of art in practice. Praxis becomes viable but constrained, maintaining itself only by the act of a splintering, by taking itself away from dominant trends.

What is needed is an aesthetic theory that critically engages with the politics of art and, in a dialectical fashion, brings theory and practice together under an all-encompassing praxis. If the medium indeed plays a part in deciding what is art and what is not, such a theory would, as is done in Hegel's philosophy of art, explore the essential elements of art and show how they create qualitative differences between different media. However, it would also have to be cognisant of and explicate the power relations that mediate social perceptions of art.

In this sense, only a synthesis between aesthetic theory and the sociology of art can provide an all-encompassing praxis for art.

The Commodification of Leisure, Part I: Art and the Culture Industry

Posted by

moses

@

18:35

•

art,

consumerism,

culture,

Marxism,

media,

philosophy,

society

•

0

comments

![]()

Here I present a reading of Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer's The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception, with reference to Frederic Jameson's essays on Adorno in Late Marxism and Amresh Sinha's Adorno on Mimesis in Aesthetic Theory.

So where should we begin? The first thing to note is the fact that there is more to Adorno and Horkheimer's theory than the suggestion of mass culture as fundamentally characterised by passive consumption. That is really only a symptom (though a very important one for Adorno and Horkheimer) of the general 'malaise' of mass culture, and one that has received far too much emphasis in media studies to the detriment of the discussion of its other aspects. In light of this, I will endeavour to present a more contextual reading of this essay.

I am looking at Adorno and Horkheimer's critique of mass culture from the perspective of their critique of pleasure as it is associated with mass entertainment under late capitalism. It should be noted that Adorno and Horkheimer's analysis of pleasure "takes place within a framework of the theory of the alienated labor process" (Jameson, 1990: 145). This entails the analysis of mass culture as the colonisation and the commodification of leisure time—amusement is the prolongation of the working day insofar as it merely functions as a period of relaxation that demands no effort (hence the passivity of the consumer), which is sold to the individual worker so that he/she can continue working contentedly the next day. Pleasure is therefore seen not only as a flight from reality but also as the flight from "any last thought of resistance" (Adorno and Horkheimer, 1998).

The full implications of commodification will be brought out later. Presently, we will attend more closely to the notion of the colonisation of leisure, which involves the mechanisation of culture that reflects the mechanisation of modern economic production: The enjoyment of culture is schematised for a passive audience so that, as mentioned above, no effort is required on the part of the latter. This entails the presentation of "repetition and the familiar" (Jameson, 1990: 148) in order not to tax the audience's minds. Thus, the familiar character of the labour process is ironically reproduced in entertainment, which indicates that the monotony of "standardised operations" that characterises the working day "can be evaded only by approximation to it in one's leisure time" (Adorno and Horkheimer, 1998).

This is where media scholars' criticisms of Adorno and Horkheimer are typically focused, with their rather belaboured emphasis on the examination of the link between media consumption and power (sometimes in an effort to deny that the media wield power over the audience). As stated in the beginning, such a perspective is sorely inadequate, and this will become evident as we examine the other aspects of Adorno and Horkheimer's theory on mass culture, beginning with its aesthetic critique of pleasure.

Adorno and Horkheimer hold that pleasure/happiness is found in what is yet to be, and their charge is that the Culture Industry offers 'inauthentic' pleasure that is purported to already exist and is ready for consumption. Furthermore, Adorno postulates a conception of the artistic mimesis as pure expression, which is antithetical to the notion of 'expressing something' (Sinha, 2000). Artistic expression is hence self-identical (Sinha, 2000) and thereby incompatible with the notion of equivalence, which is so important to the process of commodity exchange. Like the mystical in Wittgenstein's philosophy, in other words, it cannot be substituted by something else. Therefore, unlike the products of the Culture Industry, it cannot be subsumed under the mechanism of substituting means for ends (Sinha, 2000), being thus quite apart from the market for identity and leisure that under late capitalism are treated as just more commodities to be exchanged.

One important insight that we can derive from Adorno's conception of art is that, for Adorno and Horkheimer, reception is identified with the capitalist mode of production, particularly in the context of commodification. This means the reception of the products of the Culture Industry has to be understood in relation to their production. The most common criticisms of Adorno and Horkheimer are heavily invested in the critique of their claims regarding reception, emboldened by evidence indicating that audiences are not passive. Thus, a good way to uphold the Frankfurt School critique, without explicitly invoking theories of power, is to bring production back into the discourse.

Equivalence is, as stated earlier, crucial for commodity exchange, and it is created through abstraction—the Marxist account of commodity exchange involves the abstraction of the use values of goods into exchange/monetary value, "allowing comparable and measurable quantities to be manipulated" (Jameson, 1990: 149). This forms a vital part of the commodification of leisure as it is the need to conform to the principle of equivalence and create monetary value that drives the production of cultural products in a manner that is similar to the production of consumer goods, leading to the creation of what Walter Benjamin calls the mechanically reproducible work of art.

But what implications does the nature of production in the Culture Industry have on consumption? Questions of quality come first to mind, but this is, understandably, shaky ground on which to stake a critique of mass culture. We need look above and beyond, at the implications of the relations of production on the consumption of mass culture as a whole and not as discrete cultural products.

Roland Barthes asserted, mirroring Adorno's critique of pleasure, that mass-produced culture under late capitalism serves to conceal or obscure the capitalist mode of production, thereby eliminating resistance. However, this line of argument is once again susceptible to the criticism, born of audience studies, that audiences are not simply passive recipients. Indeed, I think the exact opposite is the case: Far from hiding it, the Culture Industry revels in the capitalist mode of production, showing us the promises that await us should we acquiesce to the system, namely all manner of consumer goods and the status and identities that come with them—rewards that are, however, readily available. It tempts the audience with these prizes, rather than compelling or co-opting them directly. But, crucially, it also promises the more elusive, yet-to-be prospect of success itself, embodied most vividly and blatantly by the stars it churns out as the human end-products of its capitalist mode of production. It is therefore unsurprising, though ironic in light of Adorno's linking of pleasure to readily achievable ends, that audiences are so preoccupied with stars.

Continued in Part II

Roland Barthes asserted, mirroring Adorno's critique of pleasure, that mass-produced culture under late capitalism serves to conceal or obscure the capitalist mode of production, thereby eliminating resistance. However, this line of argument is once again susceptible to the criticism, born of audience studies, that audiences are not simply passive recipients. Indeed, I think the exact opposite is the case: Far from hiding it, the Culture Industry revels in the capitalist mode of production, showing us the promises that await us should we acquiesce to the system, namely all manner of consumer goods and the status and identities that come with them—rewards that are, however, readily available. It tempts the audience with these prizes, rather than compelling or co-opting them directly. But, crucially, it also promises the more elusive, yet-to-be prospect of success itself, embodied most vividly and blatantly by the stars it churns out as the human end-products of its capitalist mode of production. It is therefore unsurprising, though ironic in light of Adorno's linking of pleasure to readily achievable ends, that audiences are so preoccupied with stars.

Continued in Part II

A pro-choice critique of choice

Posted by

moses

@

18:47

•

art,

consumerism,

culture,

media,

philosophy,

society

•

0

comments

![]()

There are some things that are perhaps confusing or seemingly very contentious in what I wrote about last. Therefore there is a need to qualify it or, more precisely, to delve into the unspoken claims behind some of the statements made. Most importantly, I think, I must talk about my perspective on choice, freedom of choice and the critique of choice.

I've written some time ago about the ability to question the choice of others. I argued that the sovereignty of the subject is illusory, since choices are often externally induced rather generated by an authentic individual will. I should add that whether there is such a thing as authentic individual will does not pose a problem to this view. In fact, if there is no such thing as authentic individual will, if choices are therefore entirely a matter of persuasion, all the more it should be possible to legitimately debate subjective choice.

There are two new things that I want to bring up here: Firstly, I want argue for the existence of general or common conceptions of what constitutes bad choices. Secondly, I want to question the non-invasiveness of subjective personal choice.

Some might disagree fiercely that what I consider bad are truly bad in any objective sense. Some might go on to say that there is nothing objective about taste. I'd like to question this last statement. Indeed, my position stems from my scepticism regarding absolute relativism even in the notoriously personal and subjective realm of tastes.

As such, I'm not so much positive of the existence of one correct theory of the good as I am sceptical of the notion that people cannot commonly share certain conceptions about what is bad. It may be impossibly difficult to find a general enough conception of the good with which we can objectively judge all choices, but it's a lot easier to find general ideas about what is bad with which we can legitimately argue that certain choices are bad.

This is a lot more obvious for choices with real material, physical and psychological consequences, but if we can establish this in the realm of tastes, it's probably safe to say that it's a solid claim. Are there instances where people commonly regard certain cultural products as lacking in quality? I think so. When I talk to people about reality TV shows, for example, I find that many would admit that certain shows are "trashy" or "bad", even if they admit to having a 'guilty pleasure' in watching them.

Perhaps this is too anecdotal, and perhaps there is a correlation between such sentiment and education level or class. However, there is still something to be said about this phenomenon.

Firstly, this implies that pleasure and people's conception of the good do sometimes diverge. Thus, it seems to contradict the central thesis of traditional hedonistic Utilitarianism, which is ironically a very popular mode of thinking. As such, good and bad is not merely a question of what consequences a choice brings in terms of utility or pleasure.

Secondly, though one might convincingly argue that common perceptions on what cultural products are bad could simply be explained by the fact that people have been told by the 'experts' about what could be considered good and what could not, all is not lost. At first glance, this may seem to corroborate the notion that nothing is objective, that what seems objective is simply the imposition of a subjective viewpoint. Yet, no matter what we think of some of those 'experts', there tends to be a process of discourse that generates and moderates the opinions offered within serious critical analyses of cultural products. Discourse, whether it is realised through an actual debate or through the influence of intellectual traditions that play off one another, lends criticism credibility as something greater than simply a collection of individualist subjective viewpoints.

Therefore, it might be that what is considered bad is something whose merits cannot be seriously analysed and discussed. Hence, it is mostly examined, if at all, merely as a symptom of a cultural trend, tending on its own to fall outside the process of discourse. What is good is a question that is debated, perhaps endlessly, in the discourse, but what is bad simply falls outside of it. The reverse is not true; what falls outside of the discourse is not necessarily bad. However, at least we now have somewhere to begin in deciding what is bad—by asking why some things don't come up in serious discussion on their own merits.

This is a bold argument, and it might come off as some kind of intellectual snobbery. But I would add that it's not necessarily a sin to enjoy something simply for any kind of pleasure that it gives. The problem is when the vast majority of what is offered can only be enjoyed in terms of the overt pleasure that it brings. Thus we come to the issue of the invasiveness of subjective choice.

If you want to do business, half the job would be done for you if you appeal to what people want. Does this mean, however, that consumer choice is paramount in production and marketing decisions? In fact, the very nature of marketing is antithetical to consumer choice. But the power of capital is not so much in forcing you to consume what you do not want, but in making you consume what you want all the time and, in the process, making you want to consume associated products as well.

Thus, the companies appeal to the lowest common denominator in order to increase sales. And they do not let your attention wander, for the sales of other cultural products and physical goods, upon which billions of units of exchange value ride, depend upon your near-undivided attention.

This is how capital imposes a near-monolithic culture on our tastes, by giving us what we want, but on their own terms and hindering our ability to emancipate ourselves from the pre-determined choices that we as consumers and members of modern society are expected to make.

But the burden of creating these circumstances does not lie on inhuman capital alone. In continuing to make the same kind of choices, we are also guilty of imposing on society a narrow range of tastes as the determinant of the cultural products that are available. Hence, our subjective choices are invasive in that, collectively, they deny other people and society at large choices that are emancipated from the dominant cultural milieu, while at the same time bulldozing through any question of quality in favour of focusing on the levels of pleasure obtained from cultural products.

Hence, like slaves who have never apprehended the notion of freedom or like the benighted denizens of Plato’s cave, we perpetually choose to live within the same kind of paradigm, not knowing what else lies outside of it, including things that convincingly possess qualitative value. The market may give us choices, but as long as we are unable to escape the paradigm of pleasure, we know that we are still fundamentally unfree.

Pig Iron: Why I like and dislike Iron Man 2

Posted by

moses

@

20:08

•

art,

culture,

film,

Marxism,

philosophy,

society

•

0

comments

![]()

I quite liked the first iteration of Iron Man on the big screen so I had more than half a mind to catch the sequel. However, I didn't manage to see it in the cinema. Fortunately, a long plane ride a few days ago afforded me the chance. And I wasn't disappointed.

For a superhero movie, it was refreshingly honest. We like Iron Man, or Tony Stark, because he is rich and 'cool', not because he is a brooding hero with larger-than-life psychological problems or teenage angst. And it featured a promising villain whom we can sympathise with, at least initially. And by that I mean real sympathy, not some sort of twisted admiration for a fictitious terrorist or madman.

But in some ways the things I like about the movie also form what I, on hindsight, dislike about it. In its portrayal of the hero, the movie embodies the culture and social consciousness of the present age: We celebrate the lucky ones, those 'blessed' with ability, means or just plain luck that ultimately makes them our heroes and icons. On the other hand, those whose lot in life are different but who struggle against it are 'doing the wrong thing'. And because they are, they must be bad—ruthless, barbaric or simply inhuman.

That's how it works, not the other way round. The latter doesn't even find chronological support in the movie. As I said, we can initially sympathise with the antagonist in Iron Man 2. However, in the end, because he is gradually shown to be cruel and inhuman, we are fine with the fact that the lucky hero triumphs. First we see the unlucky man, then the man who is (therefore) filled with the desire for vengeful satisfaction; because he was deprived, he must therefore become something less than human, destined to eventually be beaten back by his betters.

This parallels story arcs found in other contemporary stories such as the agonisingly bad Harry Potter series. It even has a close resemblance to the model of paternalism seen in the Agamemnon/Clytemnestra dynamic in Aeschylus' masterpiece more than two thousand years ago. Perhaps celebrity worship is a time-honoured tradition after all.

Having said all that, sometimes the guilty pleasure elicited by an honest Hollywood flick can remind ourselves what fools we are. But, then again, with the popularity of the Twilight series as it is, maybe the human capacity for self-reflection has been Eclipsed.

Now, at the risk of spoiling my ending, let me end with a thought: We study pop culture as a representation or commentary of contemporary society because studying it as art would just be depressing.

At the feet of the gods

Posted by

moses

@

14:16

•

art,

culture,

philosophy,

Singapore,

society

•

0

comments

![]()

I think there's something to Roger Ebert's contention that video games are not art, which he seems to have stammered out like an uncomprehending seer. And there's something amusing about the Singapore salesman who helped to swindle the public of millions of dollars for a wealthy family. Both may have something similar in mind. Both of them provoke this thought: How do we value something subjective?

The value of art is subjective because its purpose is, ultimately, that of subjective expression. And subjective expression is all that is directly relevant to the artistic process. No matter what other motivations exist in the artist's head, which purpose the artwork ends up incarnating is what we appreciate—and in art we appreciate the purpose of subjective expression.

Perhaps we need an example to illustrate this point more vividly. Think of the Pagliacci paradigm. At any moment during a performer's performance, he may have a number of motivations. He may be performing to get the performance over and done with so he could go home. Or perhaps he is performing with a conscious desire to earn some money to feed his family. But these motivations are irrelevant to his art, and if he betrays them his performance would suffer. In the theatre, the purpose that we want to apprehend in a performer's act is that of expressing the character he is playing. And so it is with all art.

If the artistic process requires subjectivity, it is opposed by the objective. Objective ideas external to the individual pollute the artistry of an object that is intended to be an artwork. Imagine an artist who has a marketing team that gives their input to the creative process based on what they expect would sell in the market. We would find the artist engaged in a process that is less about artistic creation and more about product design. That is why video games tend to be far from being purely artistic—the commercial aspect permeates and corrupts the creative process.

For that matter, artworks that are created to be sold in the marketplace might face the same problem. After all, we can see the difference between a true work of art and a souvenir. The latter is more about craft, created as a pretty or impressive thing specifically to be sold for a sum of money. Thus, if the creator is clearly motivated to create something that has objective value, especially in monetary terms, the art becomes suspect. By this reasoning, amateur art is hence the most secure in terms of its artistry—we are most assured of its subjective quality, its brilliance notwithstanding.

We can see, therefore, a crucial difference between the work of man and the work of genius. Why, then, are we so keen on translating everything into the former?

Once we try to put an objective value to the subjective, we turn something that is incommensurably valuable into something of bounded value. And, at the same time, we enter into the realm of absurdity. As the charlatan of a salesman said, "How I value my history and heritage will be different from the way you value it"—hence his valuation of a museum contribution at fifteen million dollars while 'expert' valuations put it at less than two million. We start arguing and imposing arbitrary terms.

The result is a patently uninteresting universe. Our own imagination has filled our world with numbers and robbed us of the kind of imagination that paints it with colour. No wonder boredom is the modern affliction.

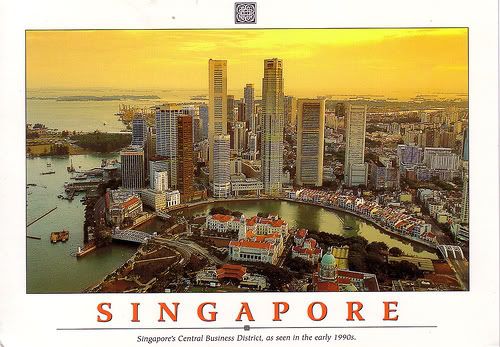

Why, seeing this, do we not complete it by fully converting the spiritual into worldly terms? Shouldn't we ask, "What price divinity?"

But perhaps we have—nature gave the pagans their gods; men in suits give us ours. On postcards there is the picture of an island of offices on a well-oiled sea. And to such a creature we yield our sacrifices. Our love's labour.