(Not) Remotely Working

@

02:19

•

covid-19,

culture,

life,

pandemic,

philosophy,

society

•

0

comments

![]()

In my previous job, I often wondered why we had to travel by air to meet clients.

On one hand, my company was very used to video conferencing. We worked with teams scattered around the globe—some in Europe, some in South Asia, and others in North America. My own team was spread across Asia-Pacific, and so were our clients. Some clients, notably tech companies, were perfectly comfortable with video calls, and we did plenty of online training to take our clients through how to use our products.

On the other hand, some clients were not, and that might mean we had to fly somewhere to have meetings, sometimes just for a few hours. And that often meant ten times the amount of time spent getting to meetings and having them versus if we had just had a video conference—and God knows how many times bigger the carbon footprint.

The company might be global and online, but a local, physical presence was sometimes demanded of it.

Fast forward to today, the world is in the grip of a pandemic. Suddenly, almost everything had to be done remotely, whether people like it or not. By now, I have had quite a lot of experience using Zoom and other video conferencing and presentation tools, and I find myself doling out advice here and there to people who are trying them out for the first time, including church groups who are moving their meetings online. Well, Jesus did say, "For where two or three gather together in My name, there am I with them." It's certainly interesting to think about Jesus lurking in the background on Zoom.

And, on that note, it's much easier to be a silent participant when you are not physically present.

Let's face it, doing something remotely is often not as effective as being present while you're doing it—whether that means time being wasted unproductively doing everything else at home, or people simply being disengaged while having an online meeting with disembodied voices. Yes, that's the price we pay for our lack of physical presence in a purposeful environment. And, of course, it's a price we can often afford to pay if we take into account the material, environmental, psychological and health costs of having to always be in an office to get something done.

But there is a price. And in the current rush to proclaim the goodness of doing things remotely, the faddish world is rushing headlong into a different extreme.

As I go through every social media posting like everyone else these days, I'm quite amazed by the sudden explosion in the number of proud introverts. Have I just never noticed, or have introverts become very extroverted about their introversion now that they have a good excuse?

I'm an introvert too, at least according to various personality tests, but I find myself kind of sad about people using the virus as a reason to fall silent and quietly drop their participation in group activities because these activities no longer involve their physical presence. I'm probably guilty of that myself. I suppose, at the end of the day, we are sensory beings, and the lack of physical tangibility might confuse our minds and our perception.

As my past study in the philosophy of mind suggests, we learn about the world through our sensory-motor functions, and hence anything that does not engage most or all of our senses may seem less real and, as such, less important to us.

Trump knows what to do (Photo: Nicholas Kamm - Getty Images)

So what does this mean in the days of #StayHome? Doing things remotely is great, and I wish people had embraced it more willingly earlier, but it does require that we invest effort into making sure we are doing things like we would if we were physically present. It means not turning into ghosts just because we can more easily evade notice. It means not letting our introvert selves turn us into phantoms of a dark basement, whose voice can only occasionally be heard.

Make remote working great again. Shut down the borders to bad home-based habits.

(Okay, I'll stop now.)

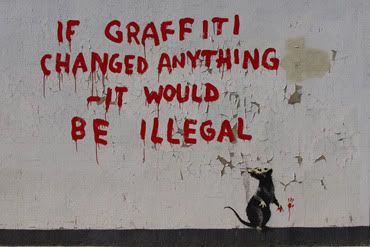

Top image created by makyzz - www.freepik.com