The question of religious faith is something very difficult to untangle in a coherent manner. And I address it despite warnings from within and without. One would hope that this question can be addressed without evoking judgemental reactions, but I don't know if that is possible. I think the best thing I can do is to be as non-judgemental as possible on my own part. And so I write this, as I had written my previous entry, with the caveat that this is what I think without claiming that it is necessarily true. But, at the same time, in support of what I'm writing, I'd like to say that it is derived from years of experience interacting with believers (it's also worth mentioning here that my views might be more relevant to Christianity than any other faith, since the vast majority of my experiences are with it), as well as a fair measure of reasoning. In other words, I'm not doing this like Ronny Tan. And now that I've mentioned it, that's a good place to start.

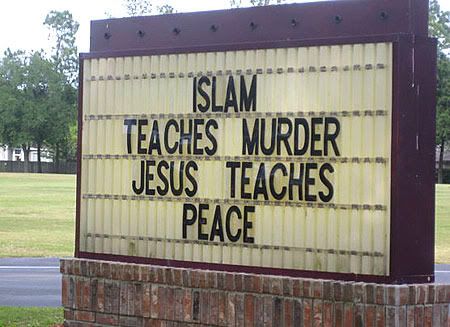

I'm mildly amused by the reactions to the Ronny Tan incident in Singapore. The issue itself, however, is of little interest to me—I know evangelistic rhetoric well enough not to be surprised. The point is I see no reason why we should pay attention to some ignorant or dissembling provocateur. I mean, in a similar way, who cares about what Westboro Baptist Church says next? If these people are vested with authority in state institutional positions, then we can talk about them being irresponsible, as with the case of Thio Li Ann. Otherwise, if we think that something said from a pulpit we don't sit below is complete nonsense, the best thing to do is to ignore it. That doesn't mean it's not important to address mistaken beliefs propagated by such rubbish. That means we ought to focus on the underlying problem, not on the nonsense itself. Hence, all the righteous anger that has emerged in reaction to what was said only seems childish and misguided. It adds nothing valuable whatsoever.

And the underlying problem is what I'm going to be referring to here: The fact that religious faith seems to have become synonymous with opted ignorance.

Recently, I've come across a notion of God that I find very appealing: God is excellence

—and it isn't just referring to moral excellence. This implies that to be faithful followers we must try as best as possible to approximate God's perfect excellence. This is very interesting, but it also raises problems with religious faith and what it means to be faithful as we have encountered them.

—and it isn't just referring to moral excellence. This implies that to be faithful followers we must try as best as possible to approximate God's perfect excellence. This is very interesting, but it also raises problems with religious faith and what it means to be faithful as we have encountered them.

Here is where I've been quite consistently disappointed by the religious community. I've met quite a few perfectly decent and intelligent people who say ridiculous things that are patently false simply because their worldview is coloured by their unquestioned beliefs. Even amongst congregations that profess to be intellectually inclined, I'm seldom ever impressed by the actual intellectual capabilities of their members. They may know their apologetics and hermeneutics very well, but they know very little about things outside their religious framework. And a good part of the reason for this is they don't see external knowledge as anything near as valuable as knowledge acquired within the faith. In other words, they are relatively dismissive of a vast amount of existing knowledge, things that could make the positions they have learned untenable (and many of them don't want to know it precisely because they are afraid of this).

I don't mean to say that believers are necessarily ignorant. Certainly, I'm not young enough to know everything either. However, I'm quite willing to learn from anything. And that is what I mean by intellectual capabilities: The unrestricted willingness to learn and the products of that willingness. Even many of the believers who are actively engaged in the pursuit of knowledge are unable to achieve this. Their pursuit of knowledge is frequently channelled by their religious sympathies, directed towards some things that conform to their beliefs and away from others that do not. And this tendency is even couched in moral terms—basically, hear no evil.

Now, I might be accused of having too much faith, ironically, in the ability of human reason to divine the truth. Of course, human minds are not perfect. But this doesn't mean reason flies out of the window. As a scholar during the Enlightenment might say, God gave us a brain, so we should use it. Indeed, even speaking within the religious framework, when people talk glowingly about the "leap of faith", I'm not sure they know what they're talking about. They are often unaware that the concept is not such a central part of established Christian schools of thought. There is plenty of emphasis on reason and rationality, which, I should add, is why people traditionally asked for signs; they wanted evidence, and the desire for evidence to support your beliefs is manifestly rational.

Similarly, when some believers talk about concepts such as "spiritual war", they are unaware that the notion borders on the heretical. And it's bad enough that believers don't know enough about their own theology, there are some groups that have virtually no theological grounding! Thus, the problem of intellectual inexcellence constitutes a vast malady amongst believers—that of a lack of inquisitiveness. They are content to be told what they like to hear and to be told that they like to hear it. And this is supposedly justified by the concept of faith or "simple faith".

One might say that that's true for any system of beliefs. But you could change your political views, for example, and it might not cost you anything. On the other hand, if you're convinced that the matter concerns your immortal soul, the equation changes.

To be fair, I've known a few believers whom I respect greatly. However, these people seem to be rare exceptions, and that is why I'm not sure whether one can be religious and be open-minded at the same time. It's a fine balance, and even the most excellence-oriented believer is quite likely to trip up. After all, if there are two things that might be true and they contradict each other, you'd simply lean towards whichever one your faith dictates.

So, as Kierkegaard was, I am sceptical towards the idea of congregations or indeed of organised religion. If a community of believers is supposed to help you nurture your faith, it certainly hasn't done mine any favours with what I've seen; so what's the point? Unlike Kierkegaard, however, I'm not willing to make the leap of faith. My willingness to learn seems to overcome that.

(0) Comments

Post a Comment