I think there's something to Roger Ebert's contention that video games are not art, which he seems to have stammered out like an uncomprehending seer. And there's something amusing about the Singapore salesman who helped to swindle the public of millions of dollars for a wealthy family. Both may have something similar in mind. Both of them provoke this thought: How do we value something subjective?

The value of art is subjective because its purpose is, ultimately, that of subjective expression. And subjective expression is all that is directly relevant to the artistic process. No matter what other motivations exist in the artist's head, which purpose the artwork ends up incarnating is what we appreciate—and in art we appreciate the purpose of subjective expression.

Perhaps we need an example to illustrate this point more vividly. Think of the Pagliacci paradigm. At any moment during a performer's performance, he may have a number of motivations. He may be performing to get the performance over and done with so he could go home. Or perhaps he is performing with a conscious desire to earn some money to feed his family. But these motivations are irrelevant to his art, and if he betrays them his performance would suffer. In the theatre, the purpose that we want to apprehend in a performer's act is that of expressing the character he is playing. And so it is with all art.

If the artistic process requires subjectivity, it is opposed by the objective. Objective ideas external to the individual pollute the artistry of an object that is intended to be an artwork. Imagine an artist who has a marketing team that gives their input to the creative process based on what they expect would sell in the market. We would find the artist engaged in a process that is less about artistic creation and more about product design. That is why video games tend to be far from being purely artistic—the commercial aspect permeates and corrupts the creative process.

For that matter, artworks that are created to be sold in the marketplace might face the same problem. After all, we can see the difference between a true work of art and a souvenir. The latter is more about craft, created as a pretty or impressive thing specifically to be sold for a sum of money. Thus, if the creator is clearly motivated to create something that has objective value, especially in monetary terms, the art becomes suspect. By this reasoning, amateur art is hence the most secure in terms of its artistry—we are most assured of its subjective quality, its brilliance notwithstanding.

We can see, therefore, a crucial difference between the work of man and the work of genius. Why, then, are we so keen on translating everything into the former?

Once we try to put an objective value to the subjective, we turn something that is incommensurably valuable into something of bounded value. And, at the same time, we enter into the realm of absurdity. As the charlatan of a salesman said, "How I value my history and heritage will be different from the way you value it"—hence his valuation of a museum contribution at fifteen million dollars while 'expert' valuations put it at less than two million. We start arguing and imposing arbitrary terms.

The result is a patently uninteresting universe. Our own imagination has filled our world with numbers and robbed us of the kind of imagination that paints it with colour. No wonder boredom is the modern affliction.

Why, seeing this, do we not complete it by fully converting the spiritual into worldly terms? Shouldn't we ask, "What price divinity?"

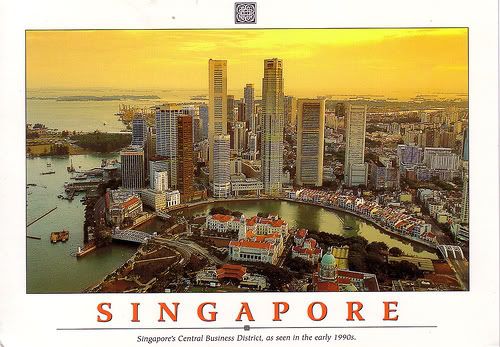

But perhaps we have—nature gave the pagans their gods; men in suits give us ours. On postcards there is the picture of an island of offices on a well-oiled sea. And to such a creature we yield our sacrifices. Our love's labour.