Losing the world and one's soul

@

07:46

•

fundamentalism,

philosophy,

religion,

society

•

0

comments

![]()

Maybe this is why one should not simply inflict the world upon a potential life.

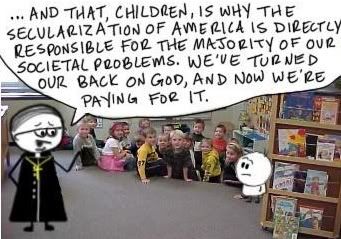

Everyday people are born, persons of flesh and blood who live and die by their physical bodies. But men of God teach that the flesh is vulgar; and some believe them. They believe that we should live not for this world, but for the next.

Think about the children born to people who hold such beliefs. From a young age they are taught that the world is a vulgar place, from whose vulgarity they need to be insulated. The unbelievers, people who are worldly and are therefore vulgar should hence be kept at arm's length. On the other hand, there are safe places filled with people who think like them, places on which divine grace shines in a special manner. These children are to grow up within the circles found there, and they are to beget children within those circles when they have grown up.

This may indeed turn out to be the good life for some of them. For a few, however, the mixture of such teachings and a dash of naivety might result in lives that are worse off.

Experience might indicate that such beliefs need to be re-examined. People may not prove to be necessarily vulgar, or men of God might prove to be just as vulgar. Or perhaps the term vulgar itself has to be re-evaluated. Yet for some of these children, naivety may prevent them from adjusting their expectations according to the reality that they experience. They were taught to insulate themselves, and in the course of their formative years they isolate themselves.

A further subgroup of them might grow up relatively oblivious to the problem that they are facing, or they might remain nevertheless firmly entrenched in the beliefs they have been taught. Others, however, might realise that the task of living has been made more difficult. Having being taught to look forward to another world, they know little about how to live in this one.

Then they begin to doubt. They question what they have been taught and why it brings them pain. What good is it to gain the world but lose one's soul, one might ask? At this rate, some of those children can gain neither. If souls actually exist, that is—we know the world exists from experience, but the existence of souls is not so clear.

So what can be done to prevent this scenario? Maybe we should worry about what happens in this life first. Or maybe we should not simply seek to propagate our beliefs through our children's lives—that should be written into a contract that parents-to-be should be made to sign.