---

---

Feel Good Inc.

Posted by

moses

@

08:46

•

charity,

consumerism,

culture,

education,

politics,

Singapore,

society

•

1 comments

![]()

All i want to say, is that we should really learn to appreciate and accept them as our equal. Maybe the next time we see them, we could perhaps just give them a simple smile, or even a word of thanks, to show our appreciation for what they are doing, I'm sure it would make their day. Or at the very least, the next time we see them, we can just try not to pull an ugly face or walk away.Thank you for taking time to read this, and although every share would not get a dollar donated or anything, but every share is a step closer to a warmer, more accepting society.

Singapore 21

Posted by

moses

@

06:44

•

#occupyrafflesplace,

Asian values,

big business,

consumerism,

economics,

education,

freedom,

GINI,

politics,

Singapore,

socialism,

society

•

2

comments

![]()

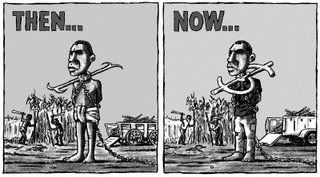

So, in light of our predicament, let me say this: Welcome to the 21st century, ladies and gentlemen. The worst is yet to be.

Simplicity/sophistication

Posted by

moses

@

21:50

•

consumerism,

culture,

identity,

media,

psychology,

society

•

0

comments

![]()

What is the simple life? Traditionally, it is understood as a thrifty life lived without pretensions. But what exactly does that entail? Are you thrifty as long as you don't buy yachts or mansions or don't live a jet setting lifestyle? Can you be free of pretensions even when you chase the latest trends and fashions?

The Commodification of Leisure, Part II: Mass Culture and Social Disorder

Posted by

moses

@

07:26

•

consumerism,

culture,

eudaimonia,

ideology,

Marxism,

media,

philosophy,

society

•

1 comments

![]()

Part I

The Culture Industry revisited

Posted by

moses

@

15:57

•

consumerism,

culture,

economics,

Marxism,

media,

philosophy,

society

•

0

comments

![]()

This vision is constructed through discourse that is sprinkled with an ever-growing list of newly-coined terms. Yet it is, at the same time, one that people can readily identify with—for who isn't ready to believe in the prospect of a brave new world, especially when the media has just informed them of the exciting new products available in the market?

Admittedly, Critical Theory does not often fare well in today's intellectual climate, a circumstance that I feel is attributable to its underpinnings in the labour theory of value, or at least in varying degrees of economic determinism. Popular conceptions of value no longer hold it as something objective or cardinal. Value is something that is purely relational and manifested in actual preferences. In other words, that people value something more than another cannot often be explained in terms of natural and tangible causes. Valuation is often a subjective affair.

In a powerful way, this undermines the Marxist critique of exchange value, not only by dispelling the labour theory of value on which the critique is based, but also by replacing the concept of use value with ordinal utility. Now we have another conception of value that is also Subject-determined and correlated with exchange value but is not equivalent to the latter. And the concept of use value seems cumbersome and obsolete beside one that is able to account for all Subject perceptions of value, including the intangible, instead of being mired in the materialist paradigm. Moreover, this conception of value is seductively democratic. After all, what can appear more empowering than a view of value that privileges people's preferences and decisions?

What this means for the Frankfurt School critique is its effective isolation as an elitist view of culture that presumes to tell people what they ought to value. If preferences are subjective, what right does anyone have to proscribe any as long as no actual harm can reasonably be alleged to result?

It is difficult to defend the Frankfurt School from such a charge. Yet I maintain that its critique of the Culture Industry still rings true, albeit in a way that may necessitate some distancing from Marxist discourse. My proposition is to look at the critique from a particularly modern perspective that revolves around expectations and hype.

If there is anything that we have learned from the last global financial crisis, it is that expectations may diverge from a more tangible reality of a situation, whatever the latter may be. Perhaps this can be seen in terms of the divergence between short-term and long-term confidence, the latter which is dependent on a stricter or more complete procedure of reasoning. But regardless of what exactly we should compare expectations to, the evidence seems to point to the existence of hype.

Hype can be understood, in that sense, as the inflating of expectations of returns relative to a more tangible measure of actual returns. Even under conventional ways of looking at the market, hype is rarely a good thing—it implies that buyers are ultimately losing out in terms of expected versus real returns to their spending. And since hype is paid for by marketing costs that are likely to figure in pricing decisions, hype also represents a potential deadweight loss.

What does this have to do with the Culture Industry? It is my contention that the Culture Industry is a major source of hype. It deals in feelings, manufacturing them in order to generate interest in things—a process that is typically subsumed under the goal of making profit. It thus becomes the primary source of trends that influence people's preferences in goods. To grasp the commercial importance of the Culture Industry under late capitalism, simply witness how advertising thrives on the products of the Culture Industry.

Moreover, this principle does not apply merely to the products of various industries, but also to more general things such as lifestyles and even happiness—the message is that spending our money on something or adopting a certain attitude or lifestyle can bring us happiness or a sense of fulfillment.

But can hype not become real if it proves to be permanent? After all, there are still many people who would be very happy to buy, for example, the latest Apple products simply on the basis of the expectations that have been generated through marketing. Thus, it would seem to be the case that these people continue to get what they expect.

Yet it remains true that no one really knows how long the ephemeral expectations that are associated with hype can last, especially on the level of the individual. All it takes is for the realisation to come, in one fine moment, that there is no basis for believing that something is as good as it has been made out to be. Much of the perceived returns would be lost in that moment, just as the perceived values of certain financial instruments evaporated a few years ago.

The lie that Culture Industry sells us does not, therefore, have to depend on a highly contentious philosophical analysis of value. Whatever the exact nature or typology of value may be, hype as the commodification of feelings can be observed in our everyday experience; and it stands clearly a means of extracting profit through the inflating of expectations.

The Commodification of Leisure, Part I: Art and the Culture Industry

Posted by

moses

@

18:35

•

art,

consumerism,

culture,

Marxism,

media,

philosophy,

society

•

0

comments

![]()

Here I present a reading of Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer's The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception, with reference to Frederic Jameson's essays on Adorno in Late Marxism and Amresh Sinha's Adorno on Mimesis in Aesthetic Theory.

Roland Barthes asserted, mirroring Adorno's critique of pleasure, that mass-produced culture under late capitalism serves to conceal or obscure the capitalist mode of production, thereby eliminating resistance. However, this line of argument is once again susceptible to the criticism, born of audience studies, that audiences are not simply passive recipients. Indeed, I think the exact opposite is the case: Far from hiding it, the Culture Industry revels in the capitalist mode of production, showing us the promises that await us should we acquiesce to the system, namely all manner of consumer goods and the status and identities that come with them—rewards that are, however, readily available. It tempts the audience with these prizes, rather than compelling or co-opting them directly. But, crucially, it also promises the more elusive, yet-to-be prospect of success itself, embodied most vividly and blatantly by the stars it churns out as the human end-products of its capitalist mode of production. It is therefore unsurprising, though ironic in light of Adorno's linking of pleasure to readily achievable ends, that audiences are so preoccupied with stars.

Continued in Part II

Our worst enemy

Posted by

moses

@

16:57

•

consumerism,

culture,

ideology,

Marxism,

politics,

society

•

0

comments

![]()

A pro-choice critique of choice

Posted by

moses

@

18:47

•

art,

consumerism,

culture,

media,

philosophy,

society

•

0

comments

![]()

There are some things that are perhaps confusing or seemingly very contentious in what I wrote about last. Therefore there is a need to qualify it or, more precisely, to delve into the unspoken claims behind some of the statements made. Most importantly, I think, I must talk about my perspective on choice, freedom of choice and the critique of choice.

Marx contra Nozick

Posted by

moses

@

17:23

•

consumerism,

culture,

freedom,

Marxism,

media,

philosophy,

religion,

society

•

0

comments

![]()

Why can we not, for the most part, refuse the bad?

Why I am an optimistic pessimist

Posted by

moses

@

13:21

•

consumerism,

eudaimonia,

life,

Marxism,

optimism,

pessimism,

philosophy

•

0

comments

![]()