Is all fair in love and work? I think many would say no, and that is partly because of a difference in attitudes that is entrenched in our culture and in our discourses on love and work.

Consider this: Well-known columnist David Brooks wrote in an article for the New York Times that young people should not "pursue happiness and joy" when deciding on their career paths, focusing instead on solving the problems they come across and seeking fulfillment through "[engaging] their tasks". On the other hand, Brooks wrote in his book The Social Animal that "The relationship between money and happiness is very tenuous; the relationship between personal bonds and happiness is incredibly strong". So we are told that happiness matters in our personal relationships but not in our jobs.

But why this difference in attitudes? How much time do we spend at our workplaces every day versus the time we spend socialising? How many friends do we see every day for durations that come anywhere close to the amount of time we spend at work? Why does happiness not matter in something that forms a significantly larger proportion of our everyday lives?

The only relationship we have with people that can come close in terms of the time and commitment that we have to invest in it is a serious romantic relationship. We might say that it's difficult or even unbearable to be in a serious relationship with someone you don't love, having to see the person daily and to pretend that, deep down, you care about him/her first and foremost. So why do some us think we can do it when it comes to our jobs?

As we are probably well aware, it comes down to a difference in motivation. It's not that happiness matters in our personal relationships and not in our jobs to begin with, it's that a lot of the time we look for happiness in our personal relationships but not in our jobs. That is quite understandable. Work occupies that space between our public and private spheres of life where necessity and practical considerations are dominant. In other words, the primary reason we work is to earn a living, and we don't often have much of a choice in that.

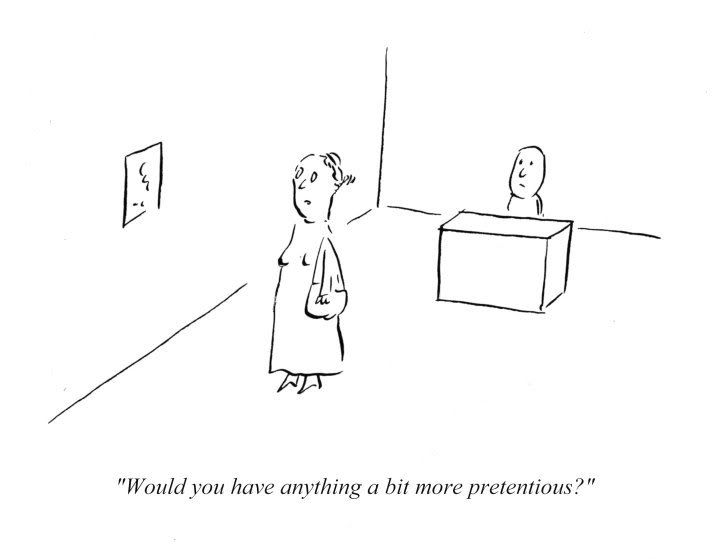

But, that said, we can still ask why we voluntarily set up a teleological barrier between work and personal relationships. Why do we judge people who enter into personal relationships out of purely material concerns? Why are people who work purely for money normal but those who seek partners for material reasons deplorable?

You might put this difference in attitudes down to a matter of frequency and significance. Serious relationships are more significant because they are harder to come by, whereas one can switch jobs relatively easily. But what difference would there be if we keep looking for jobs without putting much weight on how much we love them? Working for purely practical reasons wouldn't therefore be a temporary arrangement.

Or you might put it down to a matter bad faith. Normally, people enter into personal relationships on the understanding that it is mostly, in a strict sense of the word, personal. In other words, as we see it, personal relationships concern our persons and not so much external and material things. So in letting the latter take precedence, you would often be breaking a tacitly made contract.

Yet these days many jobs ask for passion and a degree of personal commitment that justifies the personal sacrifices that we have to make for them, often for no tangible compensation. We can no longer be assembly line workers who perform mechanical tasks while waiting for the working day to end so that we can be free to live our own lives after that. The discourse on work-life balance is increasingly making way for the discourse on work-life integration. The job is no longer something that you have to get over and done with out of necessity; it's very much a part of you as a person. Indeed, it demands to be so. Hence, if we put on a front in our jobs, aren't we similarly lying to our employers and maybe to ourselves?

So, in light of the changes in the way we live and work, is the sacred teleological divide between jobs and personal relationships defensible? Can we condemn people who treat love as labour, as an exchange to be understood in material terms? If we can lie and pretend that love or passion for our jobs is integral to our work ethic, why should we disapprove of people who pretend that love or passion is integral to their relationships? Are we just being hopeless romantics who wish to use moral indignation to protect one of the last aspects of our lives that is not touched by the paradigm of commodity exchange?

Ma Nuo, a Chinese reality show contestant, was famously blasted by the public for stating on the topic of life partners that she "would rather cry in the back of a BMW than laugh on the back of a bicycle". But wouldn't many of us rather cry in the back office of Goldman Sachs than laugh behind the counter of a café? What makes us sure that that is a morally superior sentiment?

So perhaps we can't judge people who enter into personal relationships for material or tangible gains any more than we can judge people who work purely for money. At this point, that seems to be the most logically consistent position we can have.