Singapore: Missing the Forest for the Fees

@

00:04

•

history,

identity,

ideology,

Singapore,

society

•

0

comments

![]()

This post is a social commentary I wrote as the editor of sociopolitical site Inconvenient Questions.

----------

There is an inherent tension between preservation and development. Has Singapore leaned too much towards development in its quest for economic progress? Could this tendency have eroded Singaporeans’ sense of connection to their country?

A controversy over building the Cross Island MRT Line through part of Singapore’s Central Catchment Nature Reserve flared up recently. The government has promised to consult the public and conduct careful studies before arriving at a decision, but some are not convinced that it is willing to compromise on cost.

Yet others are asking why nature lovers are so up-in-arms about this issue. Should they not be supportive of the government’s balanced approach? Are they just being irrational treehuggers?

Facts and practical arguments aside, and indeed those are not yet settled at this point, I can understand the groundswell of anger at the prospect of damaging the nature reserve. The feeling of loss is something that Singaporeans have often experienced with regard to their surroundings, and it may not get any easier each time.

As a Singaporean, one of the strategies for coping with life in Singapore is not to get too attached to your surroundings. You may love that spot, that structure, that area or that forest; the next thing you know, they might have been altered permanently or even removed.

The reasons for this can be both public and private. Spiralling rental costs have eliminated some of our favourite haunts—places like Borders bookstore at Wheelock Place, for example. Property developers keen to ensure ever-increasing rents have also gone to great lengths to ‘upgrade’ and change familiar surroundings.

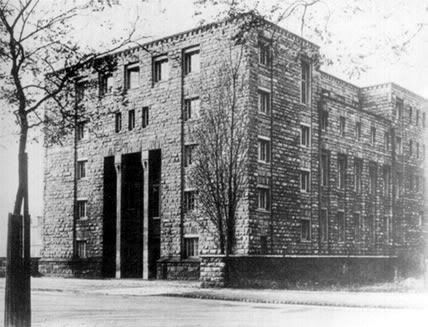

In other instances, the inexorable march of public machinery—literally and figuratively— have ripped the living proof of our memories out of existence, such as in the case of the old National Library building. If part of the Central Catchment Nature Reserve will ultimately be damaged by the construction of a new MRT line, who should really be surprised at that outcome?

A casualty of the ever-forward march of progress: The old National Library building. (Photo: Timothy)

authorities would be inclined to say “Yes”: We cannot afford to stay still, and the desire for

preservation has to be balanced with the need for development.

But if almost no place and no sliver of sentimental attachment is sacred, if we must always

be prepared to sacrifice these things at the altar of economic progress, then who can blame

people for feeling little connection to the country they live in?

Could we seek solace in artistic forms of expression? Has much of that not also been

meticulously pruned away to satisfy both a pragmatic worldview and a narrow vision of an

orderly society? So where else can we anchor our desire for meaning in being Singaporean

that goes beyond just our location and our passports?

For many of us, the answer would be family and friends—we want to live in Singapore

because they are here. But people are more mobile than ever, and communications

technology is getting better by the day. Not being here or not having a Singapore passport

does not necessarily mean losing touch with family and friends.

We may need the time and opportunity to be attached to our surroundings in order to better

appreciate what it means to live here and to be ‘locals’. Top-down feel good campaigns or

spontaneous exhortations to shout “Majulah!” can feel empty and forced. As important, if

not more important, to our sense of identity as a people are natural outgrowths of sentiment

stemming from the places, customs and languages that we live with—things that have all

been affected by at least one official campaign or another.

As things stand, the relationship for many is merely a marriage of convenience—if we really

question ourselves, how many of us are here only because the country is safe and

prosperous? What happens when there is a better prospect out there?

It is not that we can always choose to preserve everything, or that some trade-off between

identity and growth is not necessary. However, we must recognise our national ideology for

what it is; and hard pragmatism does not come without a cost. When we wonder why, as

some people do, potentially more than 50% of Singaporeans want to leave or why many

would not die for the country, we should acknowledge that the lack of personal connection

may be a price our nation pays for taking this path.

Top image created by Liyana Yeo; photo of MacRitchie Reservoir by RickDeye.