Can an immutable law be, at the same time, constrained by context and dependent upon particular circumstances for its construction and application? I think so. To put it simply, a law is made real insofar as it is known and obeyed, and its construction and application is dependent on the societies (and on the particular moments in their history) that institute it and that are governed by it. Yet the same law may have the gravity and the force of an immutable law.

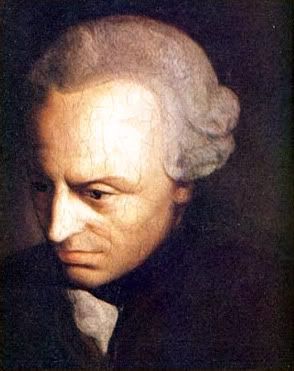

But it is not my intention here to discuss the metaphysical implications of this line of reasoning. Instead, I want to take a brief look at a pillar of Kantian ethics, which is the notion of autonomous will. As my memory of Kant's first two Critiques is sketchy, I am indebted to the SEP in writing this quick recap of Kant's moral philosophy.

Unlike the utilitarians and many other ethical systems, Kantian ethics holds that moral law is constituted not by instrumental principles that rational agents must adhere to in order to attain some form of ultimate good. Rather, moral law is founded upon the categorical imperative, which is a non-instrumental principle and which is not predicated on the existence of an abstract notion of ultimate good.

Nor is morality the product of our physiology. Unlike the central principle of, for example, an ethic that is based on empathy for others, the categorical imperative does not command us to act by virtue of what we feel (although emotions may play an important part in motivating us)—it commands us unconditionally.

Hence, we have a duty to obey the categorical imperative. But not all duties are absolutely binding—the law of the land, for example, is only binding insofar as we fall under its jurisdiction, a status we can often opt out of by leaving. The duty to obey the categorical imperative is, on the other hand, absolute because it is binding for all rational agents who are by definition "capable of guiding their own behaviour on the basis of directives, principles and laws of rationality". And we cannot opt out of our membership in the category of rational agents.

We can therefore see the connection between the categorical imperative and our status as rational agents. But the notion of autonomous will has not yet entered the picture. What role does it play in Kantian ethics? We are tempted to assume that rational agents possess autonomous will, which is a point that Kant does argue for. But how does he do so? And how is this important to the categorical imperative?

As rational agents, human beings possess rational wills, which is a will that "operates by responding to reasons". Hence, for it to be rational, it should not be entirely constrained in its operation by, for example, "being determined through the operation of natural laws, such as those of biology or psychology". To some, this might seem like an attempt to divorce reason from our biological make up, which they would regard as labouring in vain under the idealist illusion. However, Kant does not seem to go so far. He argues only that what is necessary for a will to exercise itself freely is "the Idea of its freedom", holding that having free will means not strictly operating under the constraints of immediate practical considerations when "trying to decide what to do" and "what to hold oneself and others responsible for". In other words, as I understand it, we can be said to have free will because in our practical endeavours we are capable of engaging in "self-directed rational behaviour and to adopt and pursue our own ends"; we are capable of making choices and not just of doing as the physical or material circumstances dictate.

Thus, Kant asserts that rational wills are also necessarily autonomous wills. And the significance in his ethics of the autonomy of a rational will can be found in the Kingdom of Ends and humanity formulations of the categorical imperative. Under the Kingdom of Ends formulation, a will that regards itself as a member of the category of rational wills must "regard itself as enacting laws binding to all rational wills" and thereby as a member of a “systematic union of different rational beings under common laws”—a “Kingdom of Ends” whose members "equally possesses this status as legislator of universal laws". Hence, not only must we acknowledge other people as fellow rational, autonomous beings, we must also recognise that they possess the same responsibilities as we do because they are similarly, in their capacity as rational and autonomous beings, capable of enacting universal moral laws. This is a strong basis for the concept of human dignity, a concept that is articulated in the Humanity formulation of the categorical imperative, which demands that we treat others' humanity not as a mere means to our own ends but as an end in itself.

What this means, in plain language, is that we must respect fellow human beings as equals who, like us, possess a significant basic level of dignity. This is a law that should appear immutable to us as both its legislators and its subjects; it should not be modified depending on who we're talking about or on the prevailing circumstances. Even those who are guilty of heinous crimes retain their humanity and therefore their human dignity, and the punishment meted out to them should not fail to recognise this.

All this might seem quite obvious when we think about it, but when we feel antipathy towards others for the smallest of reasons, we clearly need to remind ourselves why we shouldn't our feelings cloud our reason.

(0) Comments

Post a Comment