What has kept me going with a smile is philosophy.

In the face of the unknown, I find joy in discovering that the absurd man might be superman or overman. Vanity? No, reality.

And, in a way, I find myself agreeing the Hegelian sentiment here—while religion might have been the opium, philosophy offers the vision.

Let me explain what I mean. It begins like a story, "zeer-e gonbad'e kabood", or under the dark sky, as the Persian Shia tradition goes. One day, we wake up to discover that the world is an impersonal place. We find that it is unfamiliar to our reason and hostile to our plans. This is the moment of the absurd, as Camus describes it, the moment when we realise that our selves are subject to a universe whose laws are indifferent to our thoughts. We know then an irresistible force, but it isn't a living one; it does not know us. "Yeki-bood; yeki-nabood"—there was one, and there was no one.

But let us break away from lyricism. While Habermas, perhaps echoing Kierkegaard but from a less fatalistic perspective, says that secular reason is somewhat lost and "unenlightened about itself", Camus contends that the absurd man lives with the imperfection of reason and does not leap into what he considers the irrational—blind faith, or the obliteration of reason. The former, however, would reply that the banner of reason has only led, ironically, to a naive faith in science.

It's hard to say who's right. Yet I think Habermas has merely arrived at epistemic circularity, the practical fact that we need faith in our basic ways of perceiving and reasoning to make any sense of the world; he is probably also saying that reason doesn't tell us why we should have faith in those. And the absurd is more than admitting and living with these 'deficiencies'. It is the knowledge that what matters to each of us most in this world, the subjective self, does not square with the objective world.

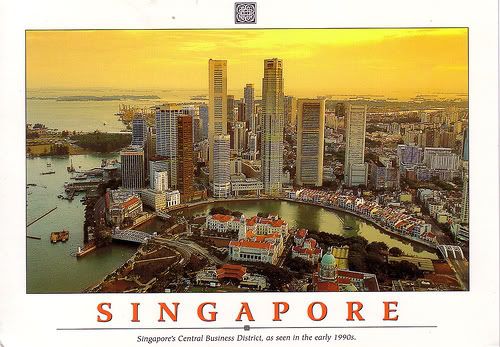

This is the reality that I was talking about, a reality where the subjective individual is alienated and dominated by the objective. We live in a world that is, in truth, very far from enlightenment; and this gulf will remain as long as we live or die by the grace of money.

That is the reality that needs lyricism. But, above all, it needs thought.

And so we tune in again. Julian Young writes in Nietzsche's Philosophy of Art that nausea, the reaction to the absurd existence, is almost a dignified condition. Down this path, he sees Nietzsche's overman as the world-affirming man, one who is willing to go through each and every experience in his life over and over, who regrets nothing. "Yes", the overman says, "the world is a hostile place—and so what?"

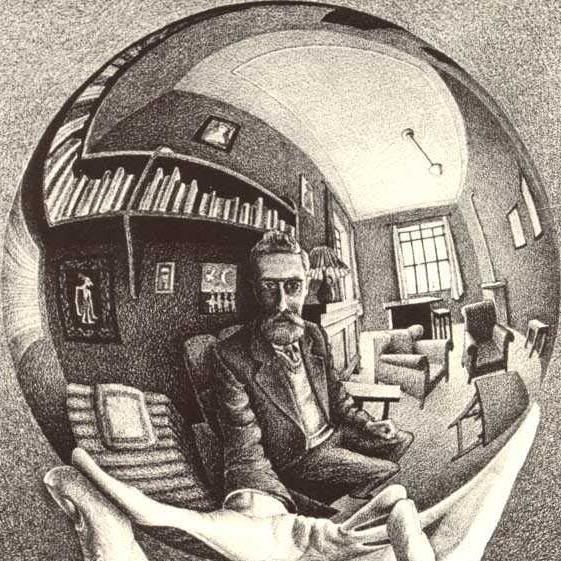

Is the overman, then, the absurd man? Have we been looking at the man in the red cape and never thought to look at any person that we might pass by in the street?

This perhaps is key: in the affirming of a harsh reality, the subjective self reveals its strength and is affirmed. While in the most agonising moments, we like critical patients might need some morphine to go on, it would not solve the problem of existence. In times, I imagine, when even your faith abandons you, you choose to live or die; and in choosing the former, what we always know as the human spirit refuses to submit itself to be obliterated.

The lyricism and the introspection, then, are not vanities. They remind us of the problem of existence. They might be our lifeblood when we lie wounded.

And in the spirit of storytelling and reflection, I've realised something else: the mourning Mother Courage, the mother of slain children who is able to stop clinging to her wares to go on is the tragic heroine of the working class.

In the end, revolutionaries might be the sons of a better age, but they should not forget themselves—lest they forget to pass over a petty careless existence.

![]()