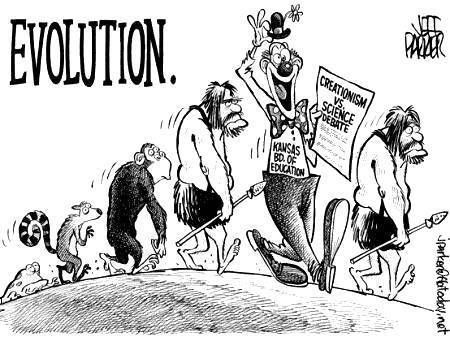

A resilient society, especially in this fast-moving age, is said to be one where the losers are allowed to be eliminated and new winners are ready to usurp the positions of those whose time has passed. Indeed, evolution (and not just the biological kind) seems to conform to this picture, with losers constantly being eliminated and the winners' positions being ever threatened by new challenges. And interestingly, the latter is what most people are blind to. The winners don't usually win forever.

A resilient society, especially in this fast-moving age, is said to be one where the losers are allowed to be eliminated and new winners are ready to usurp the positions of those whose time has passed. Indeed, evolution (and not just the biological kind) seems to conform to this picture, with losers constantly being eliminated and the winners' positions being ever threatened by new challenges. And interestingly, the latter is what most people are blind to. The winners don't usually win forever.

This picture is a positive one for society as a whole—there is continuity and everyone collectively has some chance. However, it is not one that is fair to individuals. Every person has aspirations; many want to carve their own niche. Unfortunately, most would not get there, and those who do may not stay there for very long. You may aspire to be an Alexander and become a Pyrrhus, only to die ignominiously in the streets of Argos.

Hence, while it is often to our benefit to labour under the impression that we as individuals carry weight, the reality is we can really only expect to be infinitesimal parts of the big picture. Our individual selves might matter little, while the primordial life force will thrive—Nietzsche's very vision of the Dionysian.

When we celebrate the Dionysian, we become conscious of the continuity of the whole and disregard our own individual fates. In fact, this often constitutes the essence of national projects: To work for and celebrate the success of the nation, whether or not you as a part stand to benefit yourself.

Nevertheless, self-abrogation, though often encouraged and edified by the community, will not make everyone content. Hence the illusions under which many of us labour. We need the heroic myth, the Apollonian tale of human endeavour that holds the promise of what is possible for ourselves.

This is often a necessary lie, without which we might be left despairing. Yet, again, it is one we can see past easily as we acknowledge that only a small number can attain even a shadow of the promise. Meanwhile, those whom we hail as titans of the day could soon become of no consequence, another noteworthy addendum. We are so obsessed with the present that we don't realise the heroes of today might become distant memories tomorrow. Nor do we realise that many of these 'movers and shakers' do not have the impact we attribute to them today.

Thus, wanting to make your mark on the world is virtually a pipe dream. But does that mean we can and should hope instead to make a mark in the lives of a few people? It's certainly more realistic, but we should still be wary. If we depend on others for our fulfilment, we might still be in for a rude awakening.

Arguably, and I agree with this point, finding fulfilment in our lives almost always requires the participation of other people. Nevertheless, I believe that a life too dependent on others is a life not worth living. Better seek our own happiness, with or without the involvement of others.

These are things that I have in mind as I contemplate a trip to the Orkhon Gol and the Altai Mountains, to the hinterland of those nomads who roamed the vast steppes for thousands of years. Who would know better about lives full of constant movement and change? How many people can claim to know the solitude of the infinite like the top of their saddles? Which society can better demonstrate the survival of the whole through the unquestioning generosity of the individual?

And yet these nomads, full of vigour and survival wisdom, ride at the very margins the modern world. There, in a different plane of existence that reflects all our lives, like the realm of Ideas.

Social groups are often formed around common subjects or content, but much less frequently do the latter remain the defining characteristics of those same groups.

What do I mean? To get to the point, I am referring to the problem of identification: I believe that although identification with a group is initially inseparable from agreement with its formative tenets, and the two may always remain tied to some extent, there will probably come a point where identification with the outward image of the group becomes the members' main connection to it.

Indeed, we see this very often in history and in daily life. While a nation may have been founded on principles of liberty, for example, its citizens eventually become patriots first and defenders of liberty second. And national identity, in particular, rests very heavily on the nation's outward image—on names and symbols, including flags, pledges, anthems and various other markers of identity.

Such markers of identity, which collectively form the outward image of the group, become a checklist for identification. We become concerned with questions such as "How American are you?" or "How Christian are you?" without simultaneously contemplating what those identities really entail, or might have entailed before they became nigh empty shells.

This problem is what has allowed the corruption of social groups. It is what allowed corporations to successfully court counter-culture groups such as the hippies and the hipsters, for instance, as their identity markers turned towards the domains of lifestyle and fashion. Sometimes it has even allowed groups to do an about-face and turn against everything they had stood for without loss of identity and credibility. Just look at many revolutionary governments in history, or the changing economic doctrines of Communist China.

I think the chief cause of it lies in the need for the human brain to be able to recognise easily. An evolutionary scientist might say that this has its roots in our ancestors' need to quickly recognise predators and prey. We need to recognise easily and therefore our brain takes shortcuts. We pick out certain convenient markers and associate them with the corresponding things.

On the other hand, remembering the actual content behind a group's identity requires us to remember lists or arguments that often don't come readily to mind. This unwieldy information is stored somewhere in our brain and has to be found again. Compare this to the quick and easy identification offered by markers; it's no surprise that our brains favour the latter.

Nowhere is the problem of identification better exemplified than in the world of politics. The existence of party whips in 'free' countries (a relatively benign force for party discipline), which maintain the loyalty of party members, point to a common culture that prioritises identity (i.e. in accordance with its markers) over substance. It might be worth noting that it would be unreasonable to presume instead that the whip is the constant defender of the party's tenets, as it is answerable to the ever-changing leadership.

Even without such formal enforcement, the very act of adopting a certain political label often necessitates conformity in order to be accepted and recognised within the group. So it is with other kinds of social groups.

And, in case I have not stressed this enough, for most people conformity is measured by one's adherence to the markers of identity.

I suppose this is covered by the law of economy.

But let's not talk logic here. Let's speak intuitively, so that our hearts and minds can truly engage with the issue. So this is now an existential question: Is there a 'why' in the grand scheme of things?

When I sit and listen to a sermon in a church, I am often treated to a theistic perspective of the universe. On the face of it, that seems fine. If we are honestly agnostic, a theistic perspective cannot simply be discounted.

But it gets very complex. In the Christian perspective, God has a very elaborate plan for the universe and our souls. Moreover, how this plan relates to our everyday lives is rather obscure. Hence the many books needed to explain it—and even then we are often left wondering. "Well, God's ways are sometimes hidden to us," we are told.

I'm skeptical. It seems to me that centuries of (both Jewish and Christian) doctrinal issues and debate have created a worldview with many—probably fragile—moving parts. And we don't even need to get into differences between sects and denominations.

Looking at it from the outside, it seems that the only way someone can comfortably accept such a tangle of 'truths' is if one is already primed to accept it—if one is, for prior personal reasons, already willing to accept the faith. Or, in Christian parlance, if the Holy Spirit has opened one's heart.

I see what you did there.

So even in a matter of faith existence precedes essence—the existence of the desire comes before the meaty stuff that concerns the truth of it.

And therefore, if we are skeptical of a cosmological plan, especially a very complex one, we'd probably make the same observation about the universe. There is no 'why'; it simply exists as it is. The whys belong to the domain of human beings. It is our fate and our prerogative.

I guess there is comfort in thinking that there is a grand architect, a Divine Provider who guides us. Well, it's not an unacceptable notion. I just wonder if it has to come with the incredible complexity that organised religion tends to construct.

I'm going back to the start

Posted by

moses

@

06:29

•

ethics,

life,

personal,

philosophy

•

0

comments

![]()

What might seem like simple things can indeed unravel the whole.

I don't even need to look elsewhere. I just need to look inwards. At the end of another pointless day doing mundane work for an exploitatively small wage, I feel little.

But I can blame the world for that, talk about how stupidly work is organised in this society, how for the sake of a few lines in our résumés we force ourselves to seek 'work experiences' that, in reality, teach us almost nothing.

However, there is something else I can't push away in self-pity—something that might seem much simpler on the face of it, but that might mean a lot to someone else. Something that ultimately means a lot to me as well.

At the end of another pointless day, after an errand done "on the way home" that sent me in a different direction from home, I was wishing that things were better. That was when a woman fell onto her hands and knees on the side of the path just in front of me, without a sound. I even looked. She looked like she might be ill.

And I didn't know what to do, so I walked on as though I was afraid of doing something about it. People walked past. I turned back to look after a short while, but I didn't stop. Perhaps I was hoping that she had gotten up on her own. She hadn't.

At first, after I left the scene, it bothered me a little and I thought to treat it as a lesson learned. "Next time, be sure to offer help when something like this happens."

But I couldn't think of why I couldn't have done that earlier.

Then I thought to myself, "Well, if you're going to be ruthless to get ahead in this world, maybe you shouldn't let this bother you. It was probably nothing serious anyway."

Unfortunately, I couldn't buy that thought for more than a few seconds. It occurred to me that, having walked past, I was no different from the others around me at that time. I am the same. I am the most Singaporean of Singaporeans.

This was like poison in my mind. I realised that I am not different, that I can't look past myself. I feel little. Too little to offer even the simplest of help in a little situation.

What have I got to be proud of? I have lived for a good while and I have failed to really learn anything worthwhile. I realised that, because of this, I can't be anything.

And perhaps that is my real problem—today has proven that, after more than twenty years, I have done nothing.

The ignorant critic, or happy N-Day!

Posted by

moses

@

01:44

•

economics,

patriotism,

politics,

Singapore,

society

•

2

comments

![]()

Since it's National Day, maybe I should do a bit of my patriotic duty by slamming criticism of the government. I'm proud of Singapore, man!

About a week ago, I read a blog entry complaining about the government's approach to solving the problem of insufficient parking spaces in public housing areas. Apparently, the authorities decided to double "the overnight parking fee from $2 to $4".

Cars need to find a place to park at night. You increase the parking fee, they still need to park there if they have to. How is increasing the fee from $2 to $4 going to help?

Planning guys! Planning. Either you increase the number of parking spaces or you decrease the number of cars on the road. Increasing the parking fee only give you a bigger bonus at the end of the year. It does not help anyone at all. End of the day, those car still need to park somewhere.

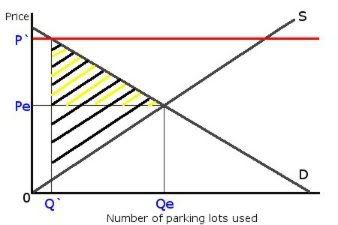

Tsk, tsk. This ignorant bad person obviously needs to get into the shoes of a bureaucrat. Here is a very simple economic model that shows the supply and demand of parking spaces and the effect of price fixing on the market, which I think is sufficient to explain the situation:

*I meant "spaces" not "lots"

The two grey diagonal lines represent the supply (S) and demand (D) 'curves' for parking spaces respectively. The y (vertical) axis of the graph measures the price of each parking lot, while the x (horizontal) axis measures the number of parking spaces used. Clearly, the graph shows the relationship between the price and the number of parking spaces used.

If the market is left to sort itself out, the common assumption is that it would default to a 'natural' sort of equilibrium. The equilibrium (default state of the market at which an equilibrium price is charged and an equilibrium number of parking spaces are used) point would be where the S and D curves intersect. So the equilibrium price would be represented by 'Pe' and the number of parking spaces used would be represented by 'Qe'. That is the point at which supply meets demand, so to speak.

However, let's say that in actual fact there aren't as many parking spaces as 'Qe'. Imagine that the S curve is vertical in the short term, since building of new car parks would take time or there just isn't enough space in the near future. Let's say there really are only 'Q`' number of parking spaces in the short term. So what happens then? The price has to correspondingly go up to 'P`' to reflect the reality of a shortage of supply.

But of course the real world doesn't quite work that way. Parking fees in public housing areas are most likely set by the authorities. That means when the authorities realise that there are too few parking spaces to meet demand, they would fix the price at a higher level in order to curb use and reserve available places for those who need them the most and are therefore willing to pay.

So what happens in the above model is the authorities would impose the price of 'P`', represented by the red line, in order to meet a target of 'Q`' number of parking spaces used. In other words, this is similar to ERP and such price-based congestion-reducing measures. You increase the price (or impose a 'tax') to decrease the number of people who are ready to use the particular infrastructure.

So what happens in the above model is the authorities would impose the price of 'P`', represented by the red line, in order to meet a target of 'Q`' number of parking spaces used. In other words, this is similar to ERP and such price-based congestion-reducing measures. You increase the price (or impose a 'tax') to decrease the number of people who are ready to use the particular infrastructure.

But why not have the S curve vertical in the model to approximate reality better? First of all, as discussed above, since parking fees are set by the authorities, I want to show the effects of price fixing rather than those of limited and very inelastic supply. Secondly, I'm not sure that 'P`' is the price that corresponds (given demand) to the actual number of parking spaces available, so I can't say that 'Q`' is the number of parking spaces available in reality. Thirdly, this is just an example using very basic economic concepts, so it may not be the best model. Lastly, this can reflect the real situation in the longer term, when there is enough time to increase the supply of parking spaces.

So one of the things worth talking about is not the fact that people still need to park their cars despite the price increase, which is neither here nor there as it skips any attempt at rational analysis, but the fact that there is deadweight loss as represented by the shaded area. However, what is more relevant in this situation is not even that, since we are speaking from the public's point of view, but the loss of consumer surplus, which is represented by the black and yellow shaded area. This area represents the utility loss of those people who don't get to use the parking spaces they otherwise would have used because the fee is now higher than they deem affordable.

Now, it's probably the case that, in the short term, demand for car parks is more inelastic than shown (D curve more vertical) so doubling the price would indeed not result in a significant reduction in the number of parking spaces used. However, this doesn't necessarily mean that people can either have nowhere to park their cars or pay up, as the blogger seems to imply. They may decide to use non-public car parks since those are no longer as expensive relative to public car parks, or they may be more willing to risk parking illegally. More importantly, in the longer run, this may discourage people from using personal vehicles, allowing the supply of car parks to catch up more easily with the demand.

So although this measure is not exactly good in the short term, it's a reasonable enough solution for the longer run. Besides, in the first place, what else can be done in the short term?

So although this measure is not exactly good in the short term, it's a reasonable enough solution for the longer run. Besides, in the first place, what else can be done in the short term?

The reality is increasing the supply of parking spaces is not a short term solution, nor is managing the trend of growing use of personal vehicles. In fact, the increase in parking fees, as I've explained, is one way of doing the latter. Furthermore, the officials quoted in the news article this blog entry cites do talk about the need for longer-term solutions, so the entry proves to be very selective in what it mentions. And it certainly ignores the fact that, from an economic point of view, the price increase would better reflect the situation on the ground, giving preference to those with greater need and hence (presumably) greater willingness to pay.

So I've written one of my longest entries ever just to discuss a relatively trivial issue. But the point isn't really to prove that blogger wrong. The point is to illustrate that you don't have to be an expert to criticise something, as many people in Singapore like to imply (when it suits their purposes), but you should at least think through what you're saying. As it is, given such a small pool of dissent in the country, there is too much crap swirling around for it to be taken seriously. Any wonder that the opposition doesn't have much credibility?

Singaporeans like to complain about small things—well, who doesn't? But get it right more often. For a nation of brilliant scorers, we say a lot of stupid things.

Now go watch the parade.

I think this is a problem that people in such a small country like Singapore don't often appreciate.

When you move to a new place, you don't know anyone and you have to build your life anew. In a large country where there actually are different towns and cities, that is, where moving would count for something. But that's fine—you just have to work on it. The trouble is if it's temporary. Then it's simply going to get torn down again. And when you get back (if you do go back), you don't know anyone anymore either.

The problem can be set up and compounded by two things: The fact that you are moving to a different country with a different culture, and the fact that your original country is a deeply impersonal place. That way, you'd be a stranger everywhere.

But we don't have to complicate things that way. We can say something about the uprooting itself. When you uproot yourself, you set before you the task of building a new life. A new network, a new schedule, new habits, a new lifestyle (to a certain extent). But the normal assumption is that this is a task of some permanence. You rebuild. You don't normally rebuild to tear down again.

So I'm in a rare enough position.

But for me there is yet another dimension to this: Leaving my hometown (which isn't where I originated), I felt that I had begun to build a life of my own, and it was good. Losing that has an impact.

Maybe I'm just sensitive. Maybe this also has to do with the fact that I left my hometown having lost almost all connection with the people around me.

Nevertheless, I think one thing is true: They say you must know your roots, but the truth is you mostly need to grow them. Where you are, that's where you need to plant. There is no home where you don't have much to hold on to.

And that will never make it into one of the National Day anthems.

It's the small things that sometimes trip up the giant.

For big problems, there are big answers. In the case of arguments against theism, for example, there is the problem of evil, which many theologians have spent much time answering. Whether or not they succeed entirely is quite beside the point here. The fact that there are substantial answers would suffice to keep theism afloat.

For small problems, however, the big answers often can't fit. Or they might simply be unable to cover every small problem.

Let's consider the notion of intelligent design. Why would there be any great imperfection (such as the existence of suffering) in the world if it was designed by an all-powerful and benevolent God? Well, a Christian might answer, God has a plan—perhaps we need to experience these large imperfections in order to grow spiritually.

But let's take a small problem. Let's say we ask why many of us continue (long after our less evolved ancestors) to grow extra teeth when our jaws might be too small to accommodate them. Would it not be absurd to say, as the answer to such a question, that "God has a plan" or that "It is because we have fallen into sin"?

To give a big answer to such a small problem would indeed strike most people as ridiculous. God planned human beings' teeth issues so that they would grow spiritually? This problem is a consequence or perhaps a punishment for falling into sin?

I suspect, therefore, that most believers would, owing to its lack of magnitude, simply shrug the problem off. However, it does not go away, and after we've accumulated enough of such problems we begin to build a strong case against intelligent design: If intelligent design is true, why do so many small imperfections exist that are clearly too trivial to serve a larger cosmic purpose?

You can't even neatly package some of these small problems as part of the larger problem of suffering—a major flaw can exist by design, but the existence of many small disconnected flaws can only point to carelessness or the lack of deliberation. The meaning of 'intelligent' would thereby become lost if one still insists that intelligent design is true regardless.

You can't even neatly package some of these small problems as part of the larger problem of suffering—a major flaw can exist by design, but the existence of many small disconnected flaws can only point to carelessness or the lack of deliberation. The meaning of 'intelligent' would thereby become lost if one still insists that intelligent design is true regardless.

So, ultimately, a cosmic scheme involving a deity with a plan simply isn't good at coming up with explanations for small factual phenomena; although it's always tentative, science can.