I'm sure we have, as consumers, critics and individuals, expended effort, time and money to look for the authentic. As tourists, we sometimes look for the authentic experience of a place; as gastronomes, we look for authentic cuisine; as individuals, we look for authenticity in matters of identity. These are but a few of the myriad instances in which we search for authenticity.

Yet, what do we mean by 'authentic'? Does authenticity exist at all? Sometimes we may even be sure that we have found it; but have we, really?

I believe that the notion of authenticity can be deconstructed or demythologised in the manner of Barthes. But why stop at revealing the class influences behind it? Studies on diasporas and postcolonial theory have also shown that the notion of authenticity is fraught with difficulties. But is there nothing more to it than the workings of ideology or a kind of collective consciousness?

Here, I want to explore the meaning of authenticity as it is cognised by the individual, to find out more about what authenticity means to each of us, if it actually means anything at all.

To a significant extent, the search for the natural parallels the search for the authentic, providing a reference with which we can understand the latter—we simply have to substitute the goal of a natural state with the goal of the original state of a human activity or creation. Hence, when we look for the authentic, we are looking for the original condition of something man-made.

The search for an original condition indicates the existence of a history. If something that we use or adopt is in its original condition, we would not need to find its original condition. However, in addition, if the history of the type of object or the practice being considered is a short one, then it is likely that we would merely be conservative in choosing to stick to the original—in other words, the notion of authenticity is not likely to be involved at all. Hence, something has to have a relatively long history or, more precisely, has to have undergone many transformations before we would be interested in rediscovering its original form.

But how often can we find the original state of something that has undergone many transformations? Human beings modify and reappropriate the things they create to fit their environment and their own uses. After numerous transformations, the original condition of something may not be knowable or recognisable to us. In instances where we think that we have found something authentic, chances are we have not found something that is in its original condition. So does authenticity have anything to do with the original condition?

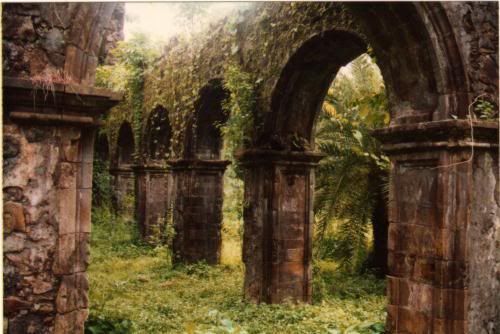

To answer this question, consider the fact that some people object to the conducting of major restoration work on ruins on grounds that the ruins would lose their authenticity. It does not seem to matter that restoration work might, ironically, bring a ruin closer to the condition of its original structure. In this light, what is so authentic about their 'authentic' unrestored forms? The quality of authenticity, therefore, has a curious tendency to be unrelated to the original condition of the object concerned.

If so, what can authenticity be reliably said to describe? I think it is precisely that authenticity is a vague and to some extent illusory concept that it is so conveniently used. While there might not be sufficient reason to be loyal to originals as simply originals, there are reasons to prefer the authentic when authenticity also connotes superiority. In fact, my contention is that the condition of being original only matters insofar as it provides a reason for claiming the superiority of an object—it is in claiming the superiority of an object that people are actually interested. Authenticity is thus another label that is frequently used as a means of distinction without necessarily denoting an innate characteristic of objects. In other words, the notion of authenticity is quite arbitrary.

In this light, I think we can certainly afford to be less concerned about authenticity. The next time you are tempted to go further for something authentic, think about saving your resources for something really good.