The world of experts is a perplexing one. And that's partly because you wouldn't know what it's really about unless you are an expert yourself.

One might think that the role of the expert can be democratised in the modern world, devolved to a larger base of 'common man' experts in a context where knowledge is widely available, thanks to a trend that can perhaps be traced from the invention of the printing press to the advent of mass literacy and most recently to the development of information technology. Apparently not.

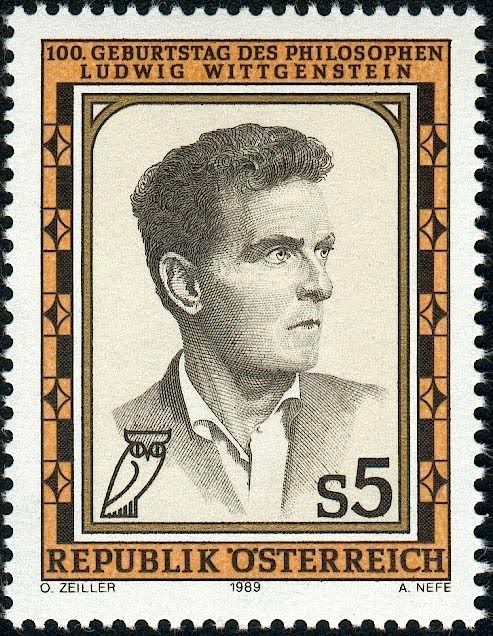

The philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein referred to "that whereof we cannot speak", a tacit kind of knowledge that agents draw upon in order to interpret meanings in a language, knowledge that can only be apprehended in its instantiation as part and parcel of practices that comprise social life. This knowledge, therefore, cannot simply be codified and read off the pages of a book or passed through any communicative medium. It has to be lived.

A field of expertise may be regarded as a kind of language, if we apply principles from structural linguistics to the wider realm of social theory. And it makes sense in this instance. Experts are experts not just because they have read a large number of texts on a subject, though that certainly helps; they are experts because they have been extensively engaged in a body of knowledge and have participated in the social activities that are central to the production and reproduction of the knowledge and the field. They literally know it inside-out.

I find the field of politics especially interesting because, rather than just interwoven with power relations in the Foucauldian sense, most knowledge pertaining to the field deals directly with power. It is therefore very relevant to everyone's lives. Are there experts in politics? Michael Oakeshott certainly thought so. Politicians, people who know the 'art' of politics through extensive experience in it, are supposedly the experts, notwithstanding their dodgy reputations and their sometimes alarming ignorance of basic facts. However, taking a cue from the title's reference to Max Weber's Politics as a Vocation, we have to be slightly careful: Are politicians the experts, or does the label more accurately apply to the political bosses?

Oakeshott seems to have had in mind the statesman rather than the campaigning or vocational politician, although the ability to acquire and retain power in a democratic context is certainly implicit in his conception. So let us treat politics in the sense that relates to governance and whatever political manoeuvring is necessary to govern a society.

A kind of elite theory of democracy that this notion of political expertise implies is consistent with a rationalisation of representative democracy. Representative democracy is held to be superior to direct democracy because 'a government by the people' is mediated by the people's representatives, the politicians, who presumably know more about what governing is really about.

I don't wish to argue for or against the notion of politics as tacit knowledge here, although I think it's undeniably true to some extent. Instead, I want to offer a critique of expertise as a myth, whereby the expert becomes a high priest of knowledge who is to be consulted and heeded, as augurs were, in an uncritical and almost superstitious manner. In other words, we sometimes think too highly of experts. And with their own interests in mind, they seldom want to correct us. Rather, they readily assume the robes of the high priest.

I've talked about instances where experts treat a given subject matter in isolation, causing them to draw bad conclusions. Here, I have in mind experts who do not even understand what they are talking about. We can have a significant amount of certainty about their ignorance when it comes to very recent political events, as insufficient time has passed to allow for an extensive body of reliable knowledge on it to emerge.

The Harvard professor who was dead wrong about the North African/Middle Eastern political upheavals comes to mind here. Yet we still see experts coming forward to offer their expert opinion on this very topic, even as events are still unfolding. It might not matter so much if they were merely at risk of being wrong, but they are also party to the framing of the present struggles of real people as political theatre, as a spectacle for entertainment or as a commodified platform for making a point. And these experts congregate or belong altogether in the media, eager to broadcast their messages to a wide audience partly because this may further their careers.

Therefore, I much prefer the historian's perspective—at the very least, the intervening dimension of time allows for observation that is more respectful and accurate. This notion has some implications on the question of whether politicians can be trusted as experts.

Not having the luxury of dealing with content that is mediated by time and yet (unlike many experts in the media) having to deal with it all the same, politicians are frequently engaging in necessary guess work. Tacit knowledge could certainly help in making ‘educated' guesses, but given the incentives involved, we don't always know whether they want to make guesses for the benefit of the public. This suggests that while it's generally pretty stupid to tell scientists that they are wrong about things like climate change, this is not the case with politicians. Experts in the natural sciences are in a completely different class compared to experts in politics when it comes to certainty in their knowledge, as well as when it comes to their integrity, occasional scandals notwithstanding.

Hence, for the sake of a publicly-oriented participatory democracy, we should feel free to take up the role of the common man political expert. It's only for our own good.