I think that's a laugh.

Showing posts with label science. Show all posts

Showing posts with label science. Show all posts

Some people claim to appreciate creation, but they don't seem to grasp just how vast the universe is.

Our awesome sun, the local star, is about as large as 1.3 million Earths. There are about 300 billion stars in our galaxy, the Milky Way. There are at least one hundred billion galaxies in the observable universe.

Is it likely that amidst all of this, we are the only sapient beings to have ever graced the universe? Isn't it simply cosmic arrogance to assume that there's one creator who made all of this just for us? That this creator babysits us and personally tends to our every need? And that he has an enemy, an antithesis, who attacks us personally?

I think that's a laugh.

I think that's a laugh.

That is not to say that secular thought escapes this problem. Since the Enlightenment, secularism is still plagued with the idea that humanity is the pinnacle of all life, which has partly resulted in our modern psychology of extreme socioeconomic (and sociopathic) narcissism.

How I wish I lived a thousand or a few thousand years from now, when we have finally learned that such thinking is folly—when we have discovered greater secrets of the universe that allows us to grasp, once and for all, that it is false. That spirit of discovery, the willingness to learn things that are beyond the scope of our everyday lives, would seem to be both the proper spiritual and scientific attitude.

Is that even conceivable to those for whom the End is always nigh? To even speak of a thousand years from now in front of some would appear to be heresy. As heliocentrism perhaps was a long time ago in an age far, far away.

I think I've had just about enough.

Often, people believe lies because they like the sound of them. It has been said that our minds are hardwired to look for patterns, even where there are none. In addition, we lock on to some of these patterns and superimpose them on things that we subsequently see. We let preconceived notions determine how we experience the world.

Certainly, such phenomena are not necessarily bad; to some extent they may even be important in helping us make sense of the world. At the same time, however, they lead us to all kinds of falsehood by making us insensitive to our actual experiences. They impose a mental processing system by which we make sense of and even twist these experiences to suit our preconceived notions.

The genius philosopher Wittgenstein devoted part of his life's work to quashing traditional philosophical thinking that falls into such a pattern. To quote a recent New York Times article on the subject:

..the non-empirical (“armchair”) character of philosophical investigation—its focus on conceptual truth—is in tension with [the goal of discovering actual truth]. That’s because our concepts exhibit a highly theory-resistant complexity and variability. They evolved, not for the sake of science and its objectives, but rather in order to cater to the interacting contingencies of our nature, our culture, our environment, our communicative needs and our other purposes.

Letting premade concepts filter our experience can inure us to authentic experiencing, compelling us into thinking that our experiences conform to those concepts. I believe that this is what makes people automatically assume that there is a god and that certain experiences are divine and must have had certain effects. It's what makes people believe in miracles that can happen any time they want.

The scientific-minded may just cite the lack of conclusive evidence for the occurrence of miracles, but this objection goes beyond that. It highlights how we, fundamentally, look at the world around us in an inauthentic way and why we are capable of seizing upon lies and integrating them into our reality. It demystifies what is at once an act of cosmic arrogance and wilful ignorance.

And the most egregious cases of this act are what I just can't stand anymore.

It is often said that knowledge is power. Is it? Or does knowledge simply avail us to the means of power, if that?

There are criticisms to be made of the naive view that knowledge can automatically solve the world's ills, but we do not even have to venture there. In the first place, we should ask what kind of knowledge is regarded as power.

It stands to reason that not all kinds of knowledge can be associated with power. But aside from the fact that some knowledge is obviously of limited use, there's a particular kind that is foremost in the hierarchy of knowledge, being perhaps the only kind that is really recognised as empowering in the minds of many: Actionable knowledge.

In a way, this is apt when we consider the naive belief that knowledge is automatically empowering. Obviously, actionable knowledge is valuable because it allows us to take actions that would otherwise not have been possible or as effective without it. On the other hand, the notion that only actionable knowledge is empowering leads to the idea that only knowledge that is actionable is worth pursuing. That is why we hear rants, such as the one in New York Times recently, about the amount of time and money spent pursuing 'useless' knowledge.

Such complaints do have their points, but they often leave us with the distinct impression that people expect a lot from the knowledge they pursue. They expect it to pave the way to good jobs, to yield financial profit, to save time—in short, knowledge is expected to have tangible benefits, measured in terms that people are already familiar with and fully expect.

There are two criticisms that can be made. Firstly, such expectations are contrary to the nature of discovery. Whether the discovery is unprecedented or personal, whether the knowledge gained is completely new or already known to others, gaining knowledge entails learning something you didn't know before. It is therefore strange that we think we know what we can expect out of gaining some knowledge. While we can perhaps guess at or imagine its possible outcomes, the process of learning is likely to entail learning more than just actionable knowledge. In any particular body of knowledge learned, perhaps only a small part of it is actionable knowledge. Yet such 'wastage' is an unavoidable part of the learning process, a consequence of not knowing what exactly to expect, and this is especially true when engaging in cutting-edge research that seeks to break new ground.

This brings us to the second point, which is what the New York Times article seems to overlook when it rehashes old complaints about the academic ivory tower: A lot of the knowledge gained through research in institutes of higher learning is 'useless' because research is not an entirely predictable process. Important discoveries are often unexpected and made when pursuing lines of inquiry that might initially seem esoteric and of limited practical consequence. Even if a body knowledge seems to be full of information that is of little use outside of academia, the discourse it generates may have a cumulative effect that could be instrumental to making important discoveries within that body or outside of it. Thus, research is not made up self-contained projects that either yield useful results or not—research can be seen as consisting of discourses that together form the ground from which new knowledge germinates, not necessarily as a result of any single effort.

That is not to say that research need not be directed by practical goals. However, we should not be surprised that only "around 40 percent" or whatever proportion of academic research proves to be immediately useful in practical contexts. These circumstances are part and parcel of the process of research, and perhaps it is a gross misunderstanding of the way knowledge is gained that leads to the kind of cynicism that demands that knowledge yield tangible rewards or be deemed not worthwhile.

Politics as tacit knowledge

Posted by

moses

@

18:12

•

media,

philosophy,

politics,

science,

society

•

0

comments

![]()

The world of experts is a perplexing one. And that's partly because you wouldn't know what it's really about unless you are an expert yourself.

One might think that the role of the expert can be democratised in the modern world, devolved to a larger base of 'common man' experts in a context where knowledge is widely available, thanks to a trend that can perhaps be traced from the invention of the printing press to the advent of mass literacy and most recently to the development of information technology. Apparently not.

The philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein referred to "that whereof we cannot speak", a tacit kind of knowledge that agents draw upon in order to interpret meanings in a language, knowledge that can only be apprehended in its instantiation as part and parcel of practices that comprise social life. This knowledge, therefore, cannot simply be codified and read off the pages of a book or passed through any communicative medium. It has to be lived.

A field of expertise may be regarded as a kind of language, if we apply principles from structural linguistics to the wider realm of social theory. And it makes sense in this instance. Experts are experts not just because they have read a large number of texts on a subject, though that certainly helps; they are experts because they have been extensively engaged in a body of knowledge and have participated in the social activities that are central to the production and reproduction of the knowledge and the field. They literally know it inside-out.

I find the field of politics especially interesting because, rather than just interwoven with power relations in the Foucauldian sense, most knowledge pertaining to the field deals directly with power. It is therefore very relevant to everyone's lives. Are there experts in politics? Michael Oakeshott certainly thought so. Politicians, people who know the 'art' of politics through extensive experience in it, are supposedly the experts, notwithstanding their dodgy reputations and their sometimes alarming ignorance of basic facts. However, taking a cue from the title's reference to Max Weber's Politics as a Vocation, we have to be slightly careful: Are politicians the experts, or does the label more accurately apply to the political bosses?

Oakeshott seems to have had in mind the statesman rather than the campaigning or vocational politician, although the ability to acquire and retain power in a democratic context is certainly implicit in his conception. So let us treat politics in the sense that relates to governance and whatever political manoeuvring is necessary to govern a society.

A kind of elite theory of democracy that this notion of political expertise implies is consistent with a rationalisation of representative democracy. Representative democracy is held to be superior to direct democracy because 'a government by the people' is mediated by the people's representatives, the politicians, who presumably know more about what governing is really about.

I don't wish to argue for or against the notion of politics as tacit knowledge here, although I think it's undeniably true to some extent. Instead, I want to offer a critique of expertise as a myth, whereby the expert becomes a high priest of knowledge who is to be consulted and heeded, as augurs were, in an uncritical and almost superstitious manner. In other words, we sometimes think too highly of experts. And with their own interests in mind, they seldom want to correct us. Rather, they readily assume the robes of the high priest.

I've talked about instances where experts treat a given subject matter in isolation, causing them to draw bad conclusions. Here, I have in mind experts who do not even understand what they are talking about. We can have a significant amount of certainty about their ignorance when it comes to very recent political events, as insufficient time has passed to allow for an extensive body of reliable knowledge on it to emerge.

The Harvard professor who was dead wrong about the North African/Middle Eastern political upheavals comes to mind here. Yet we still see experts coming forward to offer their expert opinion on this very topic, even as events are still unfolding. It might not matter so much if they were merely at risk of being wrong, but they are also party to the framing of the present struggles of real people as political theatre, as a spectacle for entertainment or as a commodified platform for making a point. And these experts congregate or belong altogether in the media, eager to broadcast their messages to a wide audience partly because this may further their careers.

Therefore, I much prefer the historian's perspective—at the very least, the intervening dimension of time allows for observation that is more respectful and accurate. This notion has some implications on the question of whether politicians can be trusted as experts.

Not having the luxury of dealing with content that is mediated by time and yet (unlike many experts in the media) having to deal with it all the same, politicians are frequently engaging in necessary guess work. Tacit knowledge could certainly help in making ‘educated' guesses, but given the incentives involved, we don't always know whether they want to make guesses for the benefit of the public. This suggests that while it's generally pretty stupid to tell scientists that they are wrong about things like climate change, this is not the case with politicians. Experts in the natural sciences are in a completely different class compared to experts in politics when it comes to certainty in their knowledge, as well as when it comes to their integrity, occasional scandals notwithstanding.

Hence, for the sake of a publicly-oriented participatory democracy, we should feel free to take up the role of the common man political expert. It's only for our own good.

It's the small things that sometimes trip up the giant.

For big problems, there are big answers. In the case of arguments against theism, for example, there is the problem of evil, which many theologians have spent much time answering. Whether or not they succeed entirely is quite beside the point here. The fact that there are substantial answers would suffice to keep theism afloat.

For small problems, however, the big answers often can't fit. Or they might simply be unable to cover every small problem.

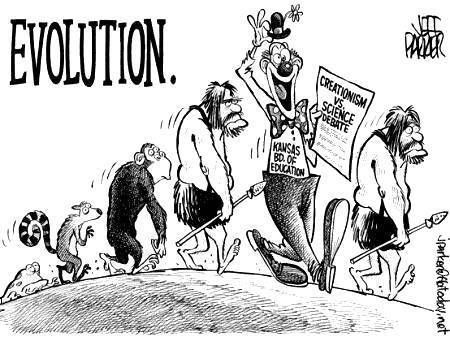

Let's consider the notion of intelligent design. Why would there be any great imperfection (such as the existence of suffering) in the world if it was designed by an all-powerful and benevolent God? Well, a Christian might answer, God has a plan—perhaps we need to experience these large imperfections in order to grow spiritually.

But let's take a small problem. Let's say we ask why many of us continue (long after our less evolved ancestors) to grow extra teeth when our jaws might be too small to accommodate them. Would it not be absurd to say, as the answer to such a question, that "God has a plan" or that "It is because we have fallen into sin"?

To give a big answer to such a small problem would indeed strike most people as ridiculous. God planned human beings' teeth issues so that they would grow spiritually? This problem is a consequence or perhaps a punishment for falling into sin?

I suspect, therefore, that most believers would, owing to its lack of magnitude, simply shrug the problem off. However, it does not go away, and after we've accumulated enough of such problems we begin to build a strong case against intelligent design: If intelligent design is true, why do so many small imperfections exist that are clearly too trivial to serve a larger cosmic purpose?

You can't even neatly package some of these small problems as part of the larger problem of suffering—a major flaw can exist by design, but the existence of many small disconnected flaws can only point to carelessness or the lack of deliberation. The meaning of 'intelligent' would thereby become lost if one still insists that intelligent design is true regardless.

You can't even neatly package some of these small problems as part of the larger problem of suffering—a major flaw can exist by design, but the existence of many small disconnected flaws can only point to carelessness or the lack of deliberation. The meaning of 'intelligent' would thereby become lost if one still insists that intelligent design is true regardless.

So, ultimately, a cosmic scheme involving a deity with a plan simply isn't good at coming up with explanations for small factual phenomena; although it's always tentative, science can.

Truth cuts both ways

Posted by

moses

@

22:39

•

economics,

Marxism,

philosophy,

politics,

science,

society

•

0

comments

![]()

I've been reading an interesting book called The Black Swan. I'm about two-thirds of the way through now and I think I have grasped the central message of the book, which is that our ability to predict the future in social matters is highly limited.

I think this is a very interesting point, and I find myself agreeing with it. I'm not so sure, however, with the seemingly suggested conclusion that a skeptical-empirical approach (which is similar to but more comprehensive than the open-minded attitude I've talked about) is linked to the libertarian position in questions of political economy. Indeed, Hayek and the Austrian school—those proclaimed bastions of libertarian thought—receive not few words of praise in the book and almost no criticism.

The thing is, Hayek might have a good point about economics, but in his political commentary he is guilty of the same thing the book criticises heavily. As I understand it, Hayek alleges that attempts to control economic activity will lead to authoritarianism, hence the 'The Road to Serfdom'. But the evidence speaks for itself. Describing, say, modern-day Britain as authoritarian is a bit of a stretch—what more labelling it as serfdom.

The truth is economic activity in modern society will always be controlled in some (not insignificant) degree, for better or for worse. And this has not and does not seem likely to result in large-scale authoritarianism. Thus, Hayek too fails when he attempts to predict a potential socio-political trend.

But I don't want to focus my criticism on Hayek. Rather, I'd like to talk about why a libertarian position does not necessarily follow from the main point of the book.

The crux of my point is this: As many have pointed out, doing little or nothing also tends to incur costs. There is a price for instituting social programs aimed at helping the impoverished, for example; on the other hand, the alternative of inaction would also have a price.

The book says that not to form quick conclusions is an act as it requires effort. Similarly, not to do something is an act as it tends to have its own cost. Hence, the lack of certainty on the possible consequences cannot justify inaction. As the book also says, having people who take their chances is often necessary for social development.

Therefore, it is rather the case that people are justified in acting on their beliefs as long as they are acting on good faith and are constantly aware of their limitations.

This leads us to another point: It is precisely the lack of absolute certainty in social matters that prevents one from judging a certain school of thought as absolutely wrong, as long as it is not in the business of making predictions or creating concrete historical narratives. So despite, say, the book's criticism of the historicity and scientism of Marxism, a non-scientific/deterministic brand of Marxism is not as vulnerable to the same criticism. Simply put, observations that are not necessarily false cannot be called out for being false.

It turns out, therefore, that under conditions of uncertainty we have to be open-minded about things that have not been proven false. But that's hardly surprising, isn't it? Except perhaps to stubborn libertarians.

Notes from the underground

Posted by

moses

@

16:12

•

democracy,

Marxism,

philosophy,

politics,

science,

socialism,

society

•

0

comments

![]()

A very common accusation made against the left-wing is that it is too idealistic. Communism fails to take into account human nature, they like to say – it's just too impractical.

Those who are fashionably or vacuously apathetic might be especially fond of this criticism. Moreover, according to many of these people, left-wingers and 'liberals' aren't just dreamers, they are also "self-righteous" bores who are always "pontificating".

As a matter of fact, there seems to be an inherent contradiction when one says that Marxism is "idealistic". Marx is said to have turned Hegelian dialectics on its head (or back on its feet) when he transformed it from an idealist to a materialist approach. Marxists generally see matter, not ideas, as the beginning and end of reality.

So why is Marxism labelled as "idealistic"? Well, you might say, that just means that it focuses on an ideal state or has an ideal state of society as its end.

What about democracy, then? Is it not essentially an ideal state of society? A few centuries ago, many would have laughed at those who extolled the virtues of democracy. It's too ideal, they'd say – the people are too unruly to rule themselves. Compare that to the common perception of it today. Many of the same people who would dismiss Marxism as too idealistic are likely to chide authoritarian regimes for being undemocratic. There's at least a tad bit of irony there, don't you think?

But democracy doesn't really have an ideal end, you might now say. It's an achievable state that has been realised and isn't aimed at creating a utopia.

Well, has it been achieved? Is the democratic process not ongoing, repeated regularly in the form of voting exercises? Does it not have to constantly face forces that seek to usurp its procedures, perhaps even powers that want people to choose to be unfree? Is it not always in conflict with the bureaucracy, the state within the state that has its own aims and its own way of doing things?

Democracy, therefore, is an end in itself, and one that will never be 'achieved' in the simple sense of the word. Democracy is a constant struggle.

And so is socialism.

Orthodox deterministic Marxism does lay claim to a scientific view that presages an inevitable Communist society, which is preceded by a period of 'socialism', a dictatorship of the proletariat. And Leninism goes on to say that this period is brought about by a revolutionary party. But these set paths and clear milestones are not necessary elements of Marxism or of its method of historical materialism.

Some Marxists believe in the constant struggle and conflict for a just society – a class struggle, the dialectics of society. Just as the struggle for democracy never really ends, this struggle is perpetual. We make no predictions or promises about a specific kind of utopian society at the end. We know, however, that struggle is the way to progress, that entrenched traditions of injustice have to be gradually worn down. And our end is the human being, who is deserving of equality and dignity.

Gradual progress is not impossible progress. It does not call for world revolution. I believe in working within the constraints of parliamentary government, in working autonomously as individuals in resisting exploitation, as well as in extra-constitutional methods – we can and should use whatever means is necessary and beneficial without contravening the over-riding principle: The equality and dignity of human life. We work towards an end, but we do not specify a particular situation as the outcome, much less do anything and everything to achieve that outcome. Marxism isn't about gulags and purges. Marxism should be humanist and highly realistic.

So, again, what is it about the left that is so idealistic? Choosing the status quo is not being realistic. Left-wingers are the genuine realists because they are attuned to reality and the great suffering that is present, which motivates them to fight for change. They are also realists because they believe that real material life is too important to be dictated by abstract ideas. Reality bears down upon us like an inexorable force. Hunger demands food; tiredness demands rest; discomfort demands alleviation. So when we are told that we have to face poverty and deprivation because of some concept or other, we find it difficult to accept, and we fight. And that is to face reality. That is what it really means to be realistic.

Now to those apathetic types, according to whom we are always "pontificating" and being merely "faux intellectual", there's not very much that needs to be said. Of course, such comments do not constitute criticism, merely some brash lashing out that likely hides an inferiority complex. And if such comments apply to us, they would apply to anyone who has argued for anything, such as in academics. Have such comments enough merit to invalidate whole fields of inquiry, just because these people have no mind for arguments?

But I think we should be quite sympathetic to them. After all, we are opposed to the real faux intellectuals – the 'experts' who treat ideas and unintelligible categories as science. In any case, the left-wing position should not be difficult to grasp. If everything else is ignored, an essential principle can still be easily understood, one that a fireman adheres to everyday: People first, property and wealth later.

True, false or free?

Posted by

moses

@

06:33

•

civil rights,

education,

freedom,

gay rights,

politics,

pseudoscience,

psychology,

science,

Singapore,

truth value,

United States

•

0

comments

![]()

Last week I wrote about what freedom means. But it might raise some questions in some people's minds. What spurs me to confidently state that freedom doesn't really apply to certain opinions? I brought up the fact that freedoms clash, and that some precede others. Thus, the freedom of speech should not be emphasized over (among others) the right to live and to pursue happiness.

Nevertheless, let's dig around a bit more. Or, rather, let's turn our eyes to the elephant in the room: Truth – as opposed to falsity or ignorance.

In all the discourse about the freedom and the relativism of opinion, we might forget that the elephant sits quietly on one side. Others pointedly ignore it. But it's there. Maybe one needs a shock before one remembers its presence. Maybe some news that would set our alarm bells off, for example – like the recent proposals being considered by the Texas Board of Education.

The conservative-dominated Board appointed six reviewers to propose changes to make to the history curriculum. Two of the three reviewers appointed by conservative board members run conservative Christian organisations, while the three appointed by the moderates and liberals are all professors of history or education at Texas universities.

Here are some recommendations that the conservative reviewers made:

Replace Thurgood Marshall with Harriet Tubman or Sam Houston.

In first grade, students are expected to study the contributions of Americans who have influenced the course of history. Rev. Peter Marshall, a reviewer, calls Thurgood Marshall – who as a lawyer argued Brown v. Board of Education and later became the first black justice on the U.S. Supreme Court – a weak example."

In first grade, students are expected to study the contributions of Americans who have influenced the course of history. Rev. Peter Marshall, a reviewer, calls Thurgood Marshall – who as a lawyer argued Brown v. Board of Education and later became the first black justice on the U.S. Supreme Court – a weak example."

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka was the case where segregated schools were ruled unconstitutional in the United States.

Delete César Chávez from a list of figures who modeled active participation in the democratic process.

Two reviewers objected to citing Mr. Chávez, who led a strike and boycott to improve working conditions for immigrant farmhands, as an example of citizenship for fifth-graders. "He's hardly the kind of role model that ought to be held up to our children as someone worthy of emulation," Rev. Marshall wrote."

Two reviewers objected to citing Mr. Chávez, who led a strike and boycott to improve working conditions for immigrant farmhands, as an example of citizenship for fifth-graders. "He's hardly the kind of role model that ought to be held up to our children as someone worthy of emulation," Rev. Marshall wrote."

César Chávez was a Mexican American labour leader and civil rights activist who made contributions to the recognition of workers' rights in the United States.

Replace references to America's 'democratic' values with 'republican' values

Reviewer David Barton suggests swapping out 'republican' for 'democratic' in teaching materials. As he explains: "We don't pledge allegiance to the flag and the democracy for which it stands."

Reviewer David Barton suggests swapping out 'republican' for 'democratic' in teaching materials. As he explains: "We don't pledge allegiance to the flag and the democracy for which it stands."

Can you see where these recommendations are going?

Now, the question that begs asking is what were these religious leaders doing making official recommendations on school curriculum in the first place? Why were actual educators and experts in the field sharing the table with them? We can infer a sad answer from the examples above, especially the third.

And this, by the way, is the Board that has approved the teaching of creationist critiques of evolution in schools.

Thus, the elephant is forgotten amidst all the politicking. And Thio Li Ann's case is another example. Let's pick just one issue amongst the many it has:

Homosexuality is a gender identity disorder; there are numerous examples of former homosexuals successfully dealing with this. Just this year, two high profile US activists left the homosexual lifestyle, the publisher of Venus, a lesbian magazine, and an editor of Young Gay America. Their stories are available on the net. An article by an ex-gay in the New Statesmen this July identified the roots of his emotional hurts, like a distant father, overbearing mother and sexual abuse by a family friend; after working through his pain, his unwanted same-sex attractions left. While difficult, change is possible and a compassionate society would help those wanting to fulfill their heterosexual potential. There is hope.

- Thio Li Ann

Compare that to the American Psychological Association's (among others) findings:

Sexual orientation has proved to be generally impervious to interventions intended to change it... No scientifically adequate research has shown that such interventions are effective or safe. Moreover, because homosexuality is a normal variant of human sexuality, national mental health organizations do not encourage individuals to try to change their sexual orientation from homosexual to heterosexual. Therefore, all major national mental health organizations have adopted policy statements cautioning the profession and the public about treatments that purport to change sexual orientation. The statement of the American Psychiatric Association cautions that “[t]he potential risks of ‘reparative therapy’ are great, including depression, anxiety and self-destructive behavior."

And the American Psychiatric Association's findings:

APA affirms its 1973 position that homosexuality per se is not a diagnosable mental disorder... APA recommends that the APA respond quickly and appropriately as a scientific organization when claims that homosexuality is a curable illness are made by political or religious groups.

Who do you trust, scientists and experts or conservative leaders with religious agendas and maybe some sinners to burn?

And, therefore, this is another compelling reason why freedom of speech is quite beside the point here. We want to argue truth, not falsity. We can talk about the freedom to hold and express an opinion all day, but if the opinion is utterly false, then nothing will be accomplished at all. And there might be a heavy price to pay too.

So, are we going to acknowledge the elephant in the room?

Well, I think I know what the Republicans might have done with theirs.