Let's face it, adults as a group are pretty bad at giving advice to young people. For example, if young people aim low, adults tell them to aim higher and have more ambition; on the other hand, if young people aim high, adults tell them to be realistic and to pay their dues first. Basically, a lot of advice actually boils down to "do/don't do what I did" or "be/don't be like me".

Then there are those who assume that people think or should think they way they do, and this group certainly includes young people as well.

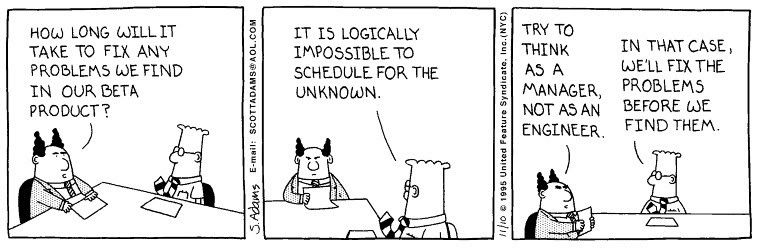

In times of great uncertainty, the advice and words of wisdom become especially loud and numerous, as everyone chimes in on what they think people should or will do. And I dare say that most of them haven't got a clue.

Now, on the Guardian's question of whether the tripling of tuition fees to £9,000 will inevitably turn students into consumers –this is a silly question and those who are happy with it are quite inevitably going to come up with silly answers. I mean, it implies that students haven't always been consumers. Does the price of a good determine whether you are a consumer? Or is there some kind of a consumer continuum? Shoppers at cheap Tesco are not as much consumers as shoppers at Waitrose?

Of course, this doesn't matter to those who wish to use the question as an excuse to air their self-righteous opinions and advice. In particular, I'm thinking of those who would take this opportunity to remind young people of the value of education, of which they are themselves naturally and keenly aware.

But instead of rushing to tell people what they should or will do, let's address the question carefully. Aside from the fact that it seems to be predicated on the strange idea that students aren't already consumers of education, there is a related question that we must first ask: What qualities can we objectively attach to consumers as a group? Certainly, there are examples of consumers behaving both rationally and irrationally. At times, they are able to make pretty good cost/benefit calculations and drive the market in a way that benefits them; at other times, they consume almost mindlessly. The diversity of consumer behaviour means we cannot assign any particular quality to consumers in their capacity as consumers and argue whether students will be more or less like them.

It also suggests that it is difficult, if not impossible, to predict how students will generally behave due to the fee increase, beyond invoking a basic economic maxim and saying that demand for higher education will almost certainly go down to some extent.

So there really isn't a good answer to the question of whether university students will become consumers, not even if we interpret it as one that is concerned with the value that future students will place on university education.

Is that a boring answer? Well, I think it certainly beats the millionth musing on how students don't value the education they are receiving enough.