The Harvard professor who was dead wrong about the North African/Middle Eastern political upheavals comes to mind here. Yet we still see experts coming forward to offer their expert opinion on this very topic, even as events are still unfolding. It might not matter so much if they were merely at risk of being wrong, but they are also party to the framing of the present struggles of real people as political theatre, as a spectacle for entertainment or as a commodified platform for making a point. And these experts congregate or belong altogether in the media, eager to broadcast their messages to a wide audience partly because this may further their careers.

The world of experts is a perplexing one. And that's partly because you wouldn't know what it's really about unless you are an expert yourself.

One might think that the role of the expert can be democratised in the modern world, devolved to a larger base of 'common man' experts in a context where knowledge is widely available, thanks to a trend that can perhaps be traced from the invention of the printing press to the advent of mass literacy and most recently to the development of information technology. Apparently not.

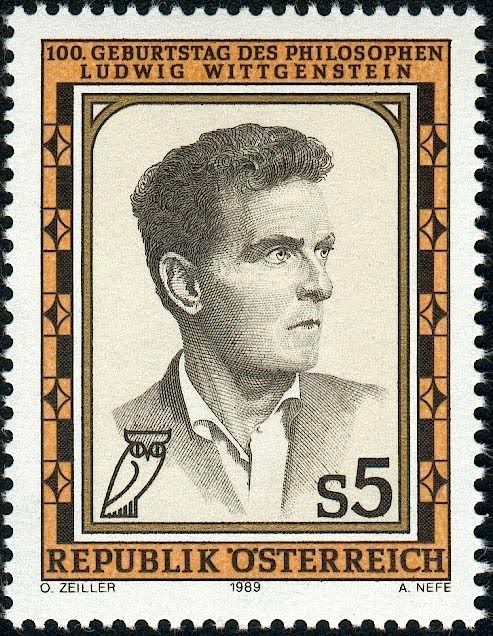

The philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein referred to "that whereof we cannot speak", a tacit kind of knowledge that agents draw upon in order to interpret meanings in a language, knowledge that can only be apprehended in its instantiation as part and parcel of practices that comprise social life. This knowledge, therefore, cannot simply be codified and read off the pages of a book or passed through any communicative medium. It has to be lived.

A field of expertise may be regarded as a kind of language, if we apply principles from structural linguistics to the wider realm of social theory. And it makes sense in this instance. Experts are experts not just because they have read a large number of texts on a subject, though that certainly helps; they are experts because they have been extensively engaged in a body of knowledge and have participated in the social activities that are central to the production and reproduction of the knowledge and the field. They literally know it inside-out.

I find the field of politics especially interesting because, rather than just interwoven with power relations in the Foucauldian sense, most knowledge pertaining to the field deals directly with power. It is therefore very relevant to everyone's lives. Are there experts in politics? Michael Oakeshott certainly thought so. Politicians, people who know the 'art' of politics through extensive experience in it, are supposedly the experts, notwithstanding their dodgy reputations and their sometimes alarming ignorance of basic facts. However, taking a cue from the title's reference to Max Weber's Politics as a Vocation, we have to be slightly careful: Are politicians the experts, or does the label more accurately apply to the political bosses?

Oakeshott seems to have had in mind the statesman rather than the campaigning or vocational politician, although the ability to acquire and retain power in a democratic context is certainly implicit in his conception. So let us treat politics in the sense that relates to governance and whatever political manoeuvring is necessary to govern a society.

A kind of elite theory of democracy that this notion of political expertise implies is consistent with a rationalisation of representative democracy. Representative democracy is held to be superior to direct democracy because 'a government by the people' is mediated by the people's representatives, the politicians, who presumably know more about what governing is really about.

I don't wish to argue for or against the notion of politics as tacit knowledge here, although I think it's undeniably true to some extent. Instead, I want to offer a critique of expertise as a myth, whereby the expert becomes a high priest of knowledge who is to be consulted and heeded, as augurs were, in an uncritical and almost superstitious manner. In other words, we sometimes think too highly of experts. And with their own interests in mind, they seldom want to correct us. Rather, they readily assume the robes of the high priest.

I've talked about instances where experts treat a given subject matter in isolation, causing them to draw bad conclusions. Here, I have in mind experts who do not even understand what they are talking about. We can have a significant amount of certainty about their ignorance when it comes to very recent political events, as insufficient time has passed to allow for an extensive body of reliable knowledge on it to emerge.

The Harvard professor who was dead wrong about the North African/Middle Eastern political upheavals comes to mind here. Yet we still see experts coming forward to offer their expert opinion on this very topic, even as events are still unfolding. It might not matter so much if they were merely at risk of being wrong, but they are also party to the framing of the present struggles of real people as political theatre, as a spectacle for entertainment or as a commodified platform for making a point. And these experts congregate or belong altogether in the media, eager to broadcast their messages to a wide audience partly because this may further their careers.

Therefore, I much prefer the historian's perspective—at the very least, the intervening dimension of time allows for observation that is more respectful and accurate. This notion has some implications on the question of whether politicians can be trusted as experts.

Not having the luxury of dealing with content that is mediated by time and yet (unlike many experts in the media) having to deal with it all the same, politicians are frequently engaging in necessary guess work. Tacit knowledge could certainly help in making ‘educated' guesses, but given the incentives involved, we don't always know whether they want to make guesses for the benefit of the public. This suggests that while it's generally pretty stupid to tell scientists that they are wrong about things like climate change, this is not the case with politicians. Experts in the natural sciences are in a completely different class compared to experts in politics when it comes to certainty in their knowledge, as well as when it comes to their integrity, occasional scandals notwithstanding.

Hence, for the sake of a publicly-oriented participatory democracy, we should feel free to take up the role of the common man political expert. It's only for our own good.

The divide between theory and practice is illusory.

I don't mean to say that there are no such distinct categories as 'theory' and 'practice'. Rather, the distinction between theory and practice is not as clear as common wisdom has it. Moreover, a sharp division between the two is a convenient illusion that is maintained for intellectual comfort.

I say this because I believe that most of those who profess to have a practical approach simply wish to do things the way they have always done them, without subjecting it to questioning and critique. They like to interact with and learn about the world as it readily appears to them. Anything else strikes them as pointless and uninteresting.

This lack of reflexivity should obviously be unsettling to anyone who values learning. But where does theory come in? Why is it necessary?

Once we go beyond the perceptually apparent, thinking in abstraction becomes our only recourse. This doesn't mean we take leave of the real world and wander into a fantastic realm. Within abstract thought referents may still be present that ground theory in the real world. Theory should begin and end in reality.

This brings us to the concept of praxis, which is the living of theory. It is where theory and practice meet, the fleshing out of the actual integration between the two. It is also the ideal, outside of which either one or the other is incomplete.

It may not always be the case that theory readily becomes praxis. However, following from what has been said earlier, as long as we keep praxis as the end point, we would not be in danger of becoming out of touch while theorising. Nor would we, as long as we are willing to employ theory as critique, put ourselves at unnecessary risk of losing reflexivity and intellectual curiosity.

Thinking in terms of a clear black-and-white divide between theory and practice is easy, but the easier way is not self-evidently the right way.

Losing the world and one's soul

Posted by

moses

@

07:46

•

fundamentalism,

philosophy,

religion,

society

•

0

comments

![]()

Maybe this is why one should not simply inflict the world upon a potential life.

Everyday people are born, persons of flesh and blood who live and die by their physical bodies. But men of God teach that the flesh is vulgar; and some believe them. They believe that we should live not for this world, but for the next.

Think about the children born to people who hold such beliefs. From a young age they are taught that the world is a vulgar place, from whose vulgarity they need to be insulated. The unbelievers, people who are worldly and are therefore vulgar should hence be kept at arm's length. On the other hand, there are safe places filled with people who think like them, places on which divine grace shines in a special manner. These children are to grow up within the circles found there, and they are to beget children within those circles when they have grown up.

This may indeed turn out to be the good life for some of them. For a few, however, the mixture of such teachings and a dash of naivety might result in lives that are worse off.

Experience might indicate that such beliefs need to be re-examined. People may not prove to be necessarily vulgar, or men of God might prove to be just as vulgar. Or perhaps the term vulgar itself has to be re-evaluated. Yet for some of these children, naivety may prevent them from adjusting their expectations according to the reality that they experience. They were taught to insulate themselves, and in the course of their formative years they isolate themselves.

A further subgroup of them might grow up relatively oblivious to the problem that they are facing, or they might remain nevertheless firmly entrenched in the beliefs they have been taught. Others, however, might realise that the task of living has been made more difficult. Having being taught to look forward to another world, they know little about how to live in this one.

Then they begin to doubt. They question what they have been taught and why it brings them pain. What good is it to gain the world but lose one's soul, one might ask? At this rate, some of those children can gain neither. If souls actually exist, that is—we know the world exists from experience, but the existence of souls is not so clear.

So what can be done to prevent this scenario? Maybe we should worry about what happens in this life first. Or maybe we should not simply seek to propagate our beliefs through our children's lives—that should be written into a contract that parents-to-be should be made to sign.

Our worst enemy

Posted by

moses

@

16:57

•

consumerism,

culture,

ideology,

Marxism,

politics,

society

•

0

comments

![]()

It might seem awfully difficult to empathise when you want something out of other people.

Indeed, the culture of selfishness that a capitalistic society fosters, for 'the good of all' (enter the invisible hand), orientates us towards the demand side of exchange. The baker does not care that you are hungry. He cares only that you are paying him good money for the bread he makes. Likewise, the buyer doesn't care if the baker has many mouths to feed in his family. He cares only that he gets the bread he wants as cheaply as he can.

This makes bourgeois culture exceedingly hostile towards perceived inefficiency in satisfying demand. We want something and we want it when we want it, the denial of which is irritating at best. The more capitalistic the society, the more hostile it is. On the producer side, this creates an atmosphere of cut-throat competition or a rat race, in which you need to offer what others can offer in order to thrive.

Unlike individual workers, however, businesses have some clout. Through political or market influence, they give themselves room to manoeuvre by ensuring that they retain some avenue for profit without always having to offer what is necessary or what is the best. Where and when they do need to compete with each other, they turn to their workers, wringing more of the latter's labour in order to increase efficiency and maximise profit.

To defend themselves, the workers have to agitate for rights and form unions to negotiate with their employers; or they could deliberately adopt inefficient practices to mitigate or spite the exploitation that they are subject to. And when they do these things, the spotlight of bourgeois wrath is turned upon them—they are seen as lazy and motivated by an unjustified sense of entitlement. This is the capitalist blame game.

Some societies may be less susceptible to such finger-pointing, but the potential for its existence is always there if we believe that human beings are inherently selfish at some level. As such, for us to rise above it, we have to actively moderate our short-sighted tendency to be selfish, to balance empathy against our desire for quick gratification. That remains virtually impossible until we stop buying into modern consumer culture—until we break the vicious cycle of capitalist ideology—for the good of ourselves as both consumers and producers.

A systematic defense of Wikileaks

Posted by

moses

@

11:45

•

ethics,

ideology,

media,

politics

•

0

comments

![]()

Having had a few garbled conversations with people where I've had to play the solitary role of a Wikileaks apologist, I'd like to do this systematically. (On a side note, who would have thought that it's Wikileaks that needs to have apologists, not the powerful organisations whose much more serious wrongdoings the former tries to uncover. This shows just how powerful ideology is in getting even ordinary people, who have little to nothing invested in it, to support the cause of governments and corporations.)

Let me begin with a very simple one-sentence argument, which I will expand on: The problem with secrets is that we cannot know and therefore make an informed judgement on them. Thus, people who are condemning Wikileaks for leaking out some 'inappropriate' information have the logic backwards, so to speak. You only know some things were inappropriate for release and are therefore condemning Wikileaks because they have been released.

Secrets, therefore, present a particularly tricky ethical problem because by definition they cannot be known, thus defying any attempt at rational analysis by which a sound ethical position can be arrived at. You cannot make an informed judgement on things that are secret, the knowledge of which is not available to you. Strange how this almost Mosaic principle in neo-classical economics is so often ignored in the neo-liberal world, for all its talk about free markets and the ubiquity of utilitarian decision making processes, which stress the ability to make informed judgements in order to maximise utility.

So you can rail against Wikileaks, but it doesn't seem to make much sense to be fundamentally opposed to its modus operandi as long as you are relying on the knowledge of the content of what it released. Also, asking Wikileaks to filter the information it gets before going public is to ask it to be yet another gatekeeper for information that only a select few can know, which seems to contradict its very raison d'être.

To reinforce this point and illustrate it in simple practical terms, let's take a look at the essential argument that the consequentialist stance entails:

Wikileaks leaked the diplomatic cables. Having seen them, I am capable of deciding for myself whether some cables should not have been made public. Therefore, I think Wikileaks was wrong to release some of them.

The second premise sits uncomfortably with an objection to the leaking of the information, which is after all being used to arrive at the conclusion. Thus, it would have to be removed in order to be consistent, which would necessitate a modification of the argument:

Wikileaks leaked the diplomatic cables. Therefore, Wikileaks is wrong.

Clearly, the argument becomes arbitrary. At best, it is inadequate—some premises and assumptions have to be filled in to make any sense of it. One way of doing so is to add "The authorities say that Wikileaks is wrong to do so" between the two sentences, thereby grounding one's ethical stance simply on what the authorities say.

Alternatively, one could acknowledge that basing one's opposition on a consequentialist argument (essentially, that leaking the cables is 'not a good thing to do') is unworkable, instead opposing Wikileaks' action on deontological grounds for 'not being the right thing to do' in principle. This position would then require a further argument regarding the ethical principles that Wikileaks have violated through the act of leaking the cables.

However, from I've seen so far, arguments to that effect seem to rely on treating public officials as private individuals who must be afforded privacy in their correspondence to each other through diplomatic channels. This argument is absurd because as long as public officials are using official channels to communicate to each other, they are performing roles on a public capacity. Therefore, the concept of privacy does not apply to them in such instances. Privacy applies to private individuals, and, as things stand, it may not even apply to the more public aspects of private individuals' lives, such as on the internet and at work. Confidentiality would be the more appropriate concept to use in this case, and it is governed by a different set of principles altogether.

Evidently, there is much work to be done disentangling some of the basic concepts and ideas involved in taking a stance on the Wikileaks issue. Being aware of the fundamental problem with secrets, I can nevertheless imagine that there are indeed certain situations where absolute transparency is not viable, especially where it directly endangers lives. However, in order to formulate rational beliefs about issues of public information, we first need to know what concepts to apply, where not to apply them and what principles may accordingly be invoked. This is what should be discussed out there in the public sphere, but I guess there won't be a slot on prime time programming as long as the public is preoccupied with blind furore over the leaks.

The present farce that is liberal democracy

Posted by

moses

@

06:53

•

democracy,

education,

Marxism,

politics,

society,

United Kingdom

•

0

comments

![]()

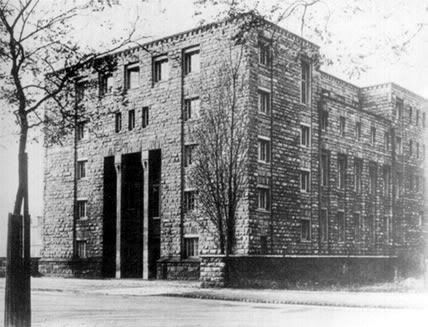

Having witnessed first hand the large student protest against the UK government's decision to raise tuition fee caps, I'm neither unnerved by the sporadic violence nor disheartened by the chaos of mass action. Rather, looking at the aftermath of the day, I've become more convinced of the corruption and the absurdity of the system.

Bourgeois sensitivity towards militant action is amusing. Repeatedly, we've been treated to condemnations of acts of violence and hooliganism by the established channels of the dominant bourgeois voice. The emphasis has been on the contrast between justified peaceful protest and bad violent protest. Perhaps if those sitting in their sofas watching the telly would reach a little into their memory and recall the last large-scale peaceful protest, they might remember the time when more than a million marched against Britain's participation in the Iraq War. The government went ahead with it anyway.

So what the official mouthpieces are really advocating is mass action that can be sidelined and ignored while the elite go on with their business. God forbid that a demonstration might make the latter anxious.

Violence is inherently problematic as it is simultaneously a powerful tool of the dominant ideology. Yet this does not diminish the idiocy of refusing to recognise the violence as a politically relevant part of this mass action. Statements about how a peaceful student movement has been hijacked by violent factions is begging the question: Where do these violent people come from and what do they want? Are they simply embodiments of the semi-mythical anarchic ruffian archetype? Or are some of them—God forbid—people who are genuinely frustrated by how they are treated by the politicians and their law enforcement minions?

While people are desperately protesting their disenfranchisement in ways that they think might have an impact, the official mouthpieces are busy trying to appeal to middle class disgust towards violence. They are also painting attacks on icons of traditional authority as appalling anti-social acts. Under this 'objective' and 'reasonable' surface discourse, ideology is plainly at work, and there is nothing too absurd for its efforts.

The attack on a royal car, in particular, has received much coverage worldwide. In Britain, some channels have been very active in expressing horror at the act. The time-honoured and sacred tradition of the monarchy itself seems to be under attack. Will those protesters stop at nothing in their quest to destroy the very fabric of society? Nevertheless, the public would be glad to know that the royalty proceeded bravely and resolutely to attend the royal variety show despite the attack.

A comedian on the show couldn't have done better.

The Odyssey

Posted by

moses

@

20:24

•

life,

Marxism,

Nietzsche,

philosophy,

self help,

society

•

0

comments

![]()

A great many thinkers have devoted much time and effort to answering this question. Camus, one of those whom I remember most clearly, gives an absurdist answer when he asks and responds to his central question: If the universe is an absurd place, why live at all?

Yet, even though he deals exhaustively with the problem of existing with the awareness of the absurd, he seems to devote little attention to the material and therefore political-economic constitution of our everyday lives. That seems to be the domain of Marxist humanist philosophy, where the question has a different formulation: How does the individual assert himself as a human subject in a society that objectifies him and his labour through processes of reification and exchange? In other words, how does one be a human being who is capable of action unencumbered by the systems of domination immanent to our commercial society?

The answer seems to be revolution, one way or another—to destroy or destructively resist the systems of domination. Yet as we live our everyday lives, it seems to me that it is often not apparent what each of us as individuals can do in that regard. Between thriving through conformity and a difficult survival in opposition to everything that our society stands for, it's quite clear what most of us would choose.

So how might we chart the happiest path in our existence, neither completely consigning ourselves to having self-destructive tendencies to give up our subjectiveness nor sacrificing ourselves as martyrs on the barricades? How do we exist as human subjects in our normal everyday lives?

Nietzsche gives a pretty compelling answer: Be a strong subject. In essence, do not bow down to the rules imposed on you by others, but strive to create your own for yourself; assert yourself as a person with minimal regard to what others want to turn you into.

This sounds like a good general principle, but how do we go about applying it? What tangible thing can we build on it and hold on to?

Moving our attention away from the will to power, which can only reproduce systems of domination and thus lead to circularity, I believe that we must live for a labour of love. In other words, instead of instrumentalising ourselves to the conventions and modes of life prescribed by society in order to live, we have to subsume the necessity of conforming under our attempts to live to work on our own magna opera. Thus, in a Marxist way, we are re-inverting the order—instead of serving the rules, we are trying to make the rules serve us.

I think this is an interesting way of thinking because it implicitly makes a few crucial points—that we are only human in doing, and that we are only subjects in being able to do what we want (in a broad and existential sense of it). And I believe these points are crucial because they inform us on how to be.

Thus the journey begins.