I was recently asked one of those questions by old people that went like this: "Is it true that young people these days are more sensitive and need to be handled gently?" My reply was that that really isn't true, or at least that's beside the point. What is true is that the younger generation today expect to be treated with respect. And, obviously, not all young people are pampered, witless kids anyway.

Certainly, the hollow and delusional pronouncements made by the dreamier ones, like the many vacuous 'Gen Y manifestos', don't do anything to help. What needs to be done is to give a proper account of the general trends in which the younger generations find themselves, and not speculate about how individual upbringing contributes to the collective character of the youth.

Complaining that young people don't have the right qualities, that they are lazy and addicted to easy living, is a recurring behaviour and tradition that dates back to ancient times. Socrates was supposed to have said, "Children nowadays are tyrants. They contradict their parents, gobble their food, and tyrannise their teachers." And such quotes from the ancients, whether or not they are verifiable, have been trotted out for centuries, suggesting that concerns about the morals and behaviour of youth are certainly not a new thing.

In this light, all the talk about the "entitled generation" seems myopic, even navel-gazing. And it overlooks the fact that the younger generations do deal with their own problems, as such perks as stable employment and certainty increasingly become a thing of the past.

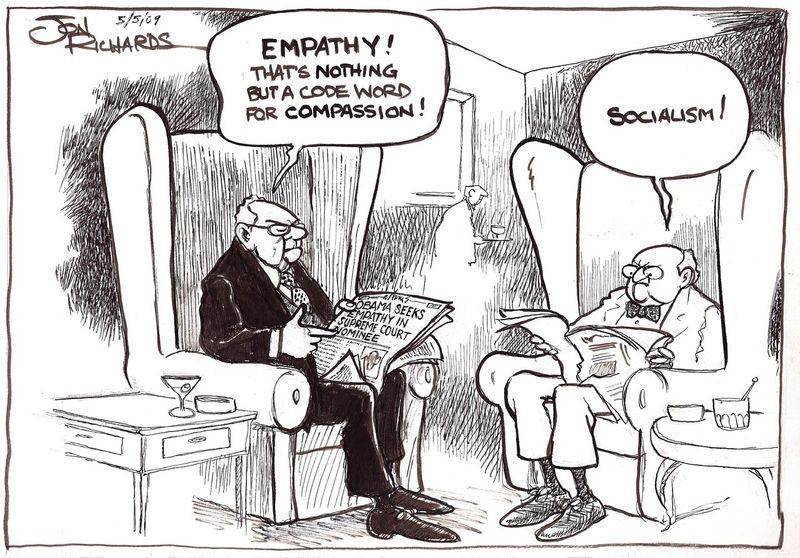

What is actually happening, then, is that society seems to be getting more used to living with the idea of democratisation. Our political and social systems are beginning to cast off the mantle of the old patriarchal, authoritarian structures, and the wide availability of information today means the elders have less of a monopoly on knowledge through their experience. This means the youth of today feel less need to be silent and quiescent before their elders and their ‘betters’. Consequently, they expect more respect from their fellow human beings and have less unquestioning respect for authority. That is why shouting at them doesn't have the effect that you were expecting.

It seems to me a positive thing if people respected each other more no matter who they are. Thus, it seems that this is something that the older generations can learn from the youth of today. Are they willing to accept this, though, or will they stick to their guns? How they react would show which generation is in fact the better one.