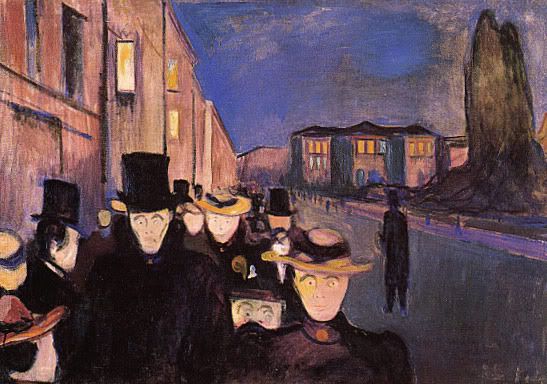

It's new year's eve again, and I feel no compunction to join the merry-makers out there. As it would often seem to me, New Year's Day is just another day. Why would I suffer the vicissitudes of a crowded night in anticipation of it?

This year, though, I do feel that the coming of the year has some sort of significance—perhaps as a celebration of the passing of days past and of hope for the future?

Well, you're likely to reap what you've sowed for the past year or even earlier, so you shouldn't be too surprised at what's coming. And wishing for luck is meaningless. I just don't like the vague idea of hope, without a good reason behind it, as it soon translates disappointment—as many will find out once again.

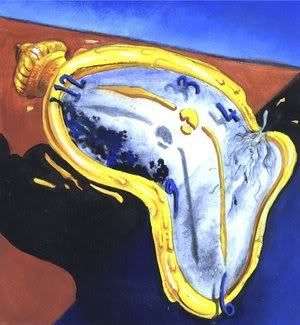

Maybe, for this year, the fact that the new millennium is entering into its teens is a fact worth celebrating? After all, when will you see a 9-year-old millennium turn 10 again? But, the interesting idea aside, does that really make a difference?

It seems hard to find much significance when the coming of the year does not by itself bring about change. But I think I found a good and simple answer.

Ultimately, the greatest meaning that could be ascribed to the occasion lies not so much in looking towards the new year as in looking at the passing one. And it's not to look at the past for some sort validation for present decisions on the future, but to look at past mistakes and to learn from them.

I think that's what new year resolutions amount to if they're any good at all—you tell yourself not to repeat the mistakes of the past year (or years). That's much more concrete and meaningful than having a vague and ephemeral hope for the coming year, or a determination to do a random assortment of things that you don't have much reason to believe you would end up doing. It gives a genuine reason to be hopeful.

And with that in mind, I hope you have a happy new year.