Don't bet on the Batman

@

16:37

•

art,

culture,

film,

heroes,

media,

psychology,

society

•

0

comments

![]()

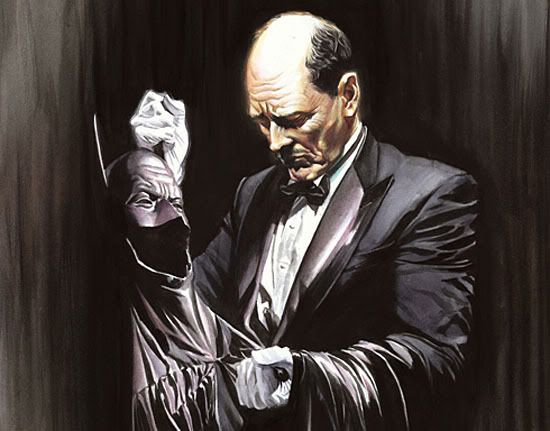

Upon hearing that a massacre had occurred during a premiere of the latest iteration of the Batman films, some people asked, "Where was Batman?"

Perhaps the joke, all jokes are not an appropriate response to such a tragedy. But this is also a singularly powerful question. Indeed, where was—is—Batman?

Of course. He's not real. Batman is fiction. Everyone except some kids (and maybe some delusional fools) knows that. People can be expected to know the difference between reality and the superhero fiction, can't they? Well, can they?

Most people know that superheroes don't exist. But to what extent do they grasp this fact? I mean, why do people like superhero stories? The modern trend in fiction may be to humanise superheroes, to depict the conflicted and flawed hero. But they're still superheroes—they are still powerful; they can still solve the world's problems, even if they must bleed and sacrifice much in the process. Perhaps stories like Watchmen defy this convention altogether, but not the Batman films.

Christopher Nolan's Batman is a tortured hero, a hero who has to mask himself as a villain. But the audience are well aware that he is hero. And the fantasy of the mighty superhero, furthermore, is not shattered. People can expect Batman to save the world within the big screen. They want to savour—even just a shadow of it—the excitement that springs from the knowledge that a saviour is here to fight for them. Fiction melds with reality; the story is not real, but physiological reaction to it is.

That is why the massacre is semiologically powerful—a horrible crime is occurring while the superhero is 'present' on the big screen, a demonstrably flat image that interacts with the world purely as illusion. It's not even impotent; it's nothing at all. The mirage is shattered completely by the jarring reality of a tragedy unfolding simultaneously. Thus, observers may be prompted to ask, "Where was this hero?" Of course they'd known that he doesn't exist. But this incident makes them realise that anew and takes the realisation to a higher, uncanny level.

The death of the superhero, a theme that has been explored in fiction, is not as devastating to the fantasy as the real deaths of superhero fans in front of the big screen.

However, while many of us may intuit this, not everyone will realise what it means. Take, for example, this Facebook comment about the survivors:

All I can say is send them a hero Chris send the dark knight to the hospital for them, so the children know there are real heroes out there, and that evil won't win

This is exactly the kind of sentiment that should have been extinguished by this incident. Yet people want to hold on to the fantasy and, worse, to perpetuate it by instilling the same delusion in children—the notion that there is a simple fix to the big problems that can be accomplished by a few mighty and benevolent individuals.

Perhaps adults have a vested interest in raising children who are naïve and docile. Some of them had probably been raised to be that way themselves. But the use of a crutch is symptomatic of disability—this much-needed delusion reveals people's psychological inability to steer away from a petty existence waiting for salvation.

Those people have got it the wrong way around. If they did exist, superheroes would exist because people are unable to fight for themselves. Thus, instead of wishing that they did exist, we should want their existence to be unnecessary. That, not having a superhero around, would be truly empowering.

(0) Comments

Post a Comment