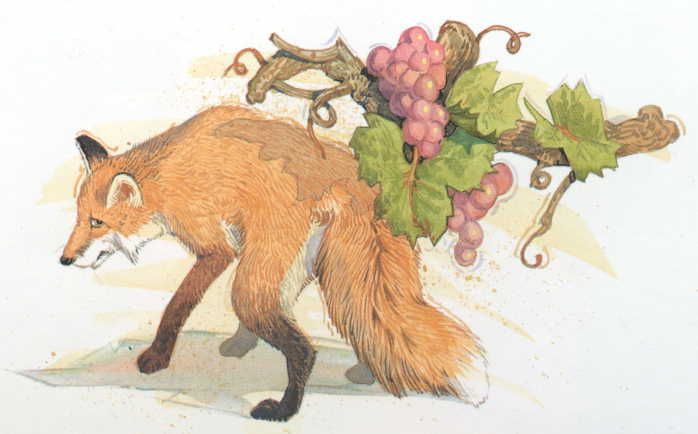

Illustration by Don Daily

As a debate plays out this weekend regarding the use of Singlish, let us recall the fable of the Fox and the Grapes. It's a story that is familiar to us, in which a fox, unable to reach some grapes, disparages them as sour grapes.

The term 'sour grapes' has come to signify envy, but there is an element of the pathetic in the fable: Unable to obtain something, the fox takes refuge his rejection of that thing.

Those who entertain thoughts of replacing English with Singlish should remember this tale. The idea of replacing English entails doing away with it altogether, and, if they have resistance in mind, that would not constitute a gesture of resistance.

Why is that so?

An act of resistance without a centre or a point to which it is opposed is untenable. While it might seem clear that communicating in Singlish can be conceived of as an act of resistance that is externally directed against the officious imposition of standard English, it would—recalling the fable—be reduced to a desperate cry if it does not arise from an internally-directed conflict.

This argument is motivated by the mirror-image of the maxim that external opposition is inevitably a reflection of internal contradiction—that a deliberate work of art must be internally coherent to project a meaningful opposition externally. The act of speaking Singlish, if it is to be a performance that mimetically mocks or deconstructs official language, must achieve this internal coherence through the act of conscious and deliberate resistance by the speaker, who has the capability to communicate in standard English and yet chooses not to do so. Without this capability and the actor's power to choose to begin with, the act loses its strength.

It seems eminently foolish to oppose centres of power by reducing what power you have to enact gestures of resistance. Even if those who are for replacing English do not intend it as an act of resistance, their position would still be tantamount to advocating the weakening of the power to resist standard English as a symbol of coercive authority. That would certainly impoverish any speak Singlish movement.