Reason may the highest human faculty, but it is not always perfectly grasped.

The intellect can be a selfish thing—and that's the consequence of an epistemological problem; perhaps the epistemological problem. We are the centre of our universe (or lifeworld) and it is a position that we can never escape. Everything that we interact with we interact with in relation to ourselves, whether through our physical selves or through our Ego or the equivalent. As a result, the tendency to view others in relation only to ourselves is prevalent.

This epistemological problem is present in metaphysics as well, potentially leading to solipsism, or the idea that minds apart from one's own do not exist.

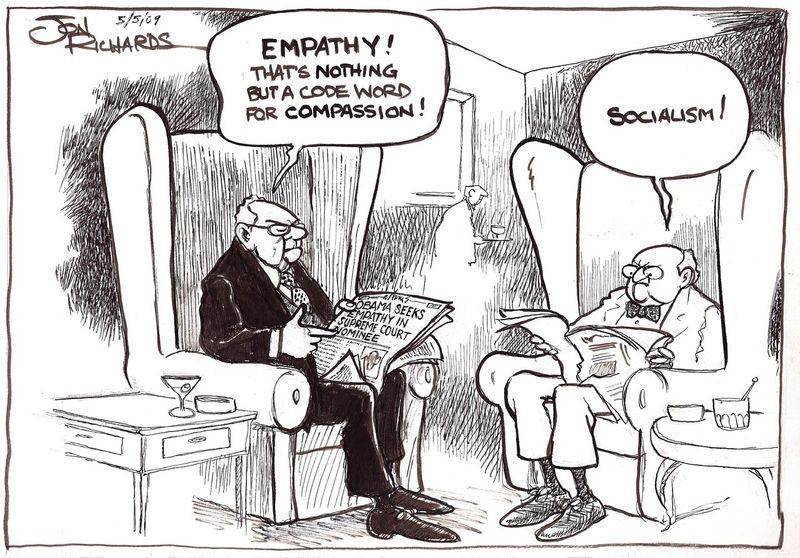

Much as empathy, the ability to see or feel other minds as equivalents of one's own, offers a solution to the problem of solipsism, it also offers a solution to the problem of selfishness in ethics. Being able to approximate the experiences of others in one's mind allows one to appreciate their experiences and thereby establish a kindred connection between Self and Other.

This is a powerful connection that can succeed where reason has failed. While it is certainly possible for one to hold fast to ethical precepts, the abstraction of these precepts cannot match the tangibility of the simulated experiences generated in an emphatic connection.

And the beautiful thing about empathy is this—it allows us to see others in terms of our own selves, thus short-circuiting the solipsistic tendency by transferring our selfness onto others so we could act (or react) as though prompted by our own experience.

This may be a simplistic way of looking at this matter, but it's a start.

Many Singaporeans are accused of being armchair critics who criticise their government and their country without grasping the finer points of governance. That is often true enough, but sometimes the armchair critics are on the other side. One such example is a blog post by a travel writer who lambasts Singaporeans for their "hypercriticality". Below, I have reproduced my reply to the post.

---

Wow... where do I begin? A wealthy tourist likes a place and goes on to proclaim that the people who live there just don't appreciate what they have. Can you see where this is going?

Yes, sometimes one needs to take a step back to get some perspective. But, to put it bluntly, why do you presume to be able to tell those people 'the truth' either? Do you not realise that you too have a particular perspective that is lacking in its own way; i.e. lacking in the everyday experience of living in that place you're talking about.

If couched as a simple reminder to take a step back or a deep breath, then, sure, you may be doing those people a service by writing this. But, as it is, the piece literally compares the people you're discussing to children. If that is not extremely patronising coming from an outsider, then I don't know what is. It's reminiscent of colonial writers from the empire writing about the colonies and their denizens without a serious attempt at understanding the subject matter. It's presumptuous and sickening.

I'm not trying to make this personal. Perhaps I'm being, in a typical way, "hypercritical". But I'm truly astounded by the lack of perspective this piece itself exhibits. And, if it makes sense, that deficiency takes the form of being ostensibly unaware of its own perspective.

The ineffectual complainer is a hateful figure. But much more insidious is the ever-accepting positive person who is a force of inertia in society.

Chances are you know a few: The people who are always trying to get others to look on the bright side; who cannot accept any negativity; who may regard any criticism as unproductive by definition, professing to prefer 'action' (regardless of whether action by itself would actually change anything).

These types are insidious and even downright dangerous because they are disarmingly benign. They are also eminently lovable—certainly to the recipients of criticism, but also because they engender positive emotions in others who are taken in by their attitudes. They negate critique and actively try to get society to ignore ugly truths.

Suppose a man-made disaster happens in a society. These are the people who would advocate not pointing fingers—as was the case in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis. They ignore the fact that not laying any blame would likely result in similar disasters happening again in the future, due to the failure to enforce any form of accountability.

Even if these positive people are simply genuinely positive by nature, they must always be treated with a healthy dose of skepticism. It may be difficult—their positive emotions are infectious. But if they are allowed to be dominant, society's progress towards a more positive future would, ironically, be slowed.

I think I've had just about enough.

Often, people believe lies because they like the sound of them. It has been said that our minds are hardwired to look for patterns, even where there are none. In addition, we lock on to some of these patterns and superimpose them on things that we subsequently see. We let preconceived notions determine how we experience the world.

Certainly, such phenomena are not necessarily bad; to some extent they may even be important in helping us make sense of the world. At the same time, however, they lead us to all kinds of falsehood by making us insensitive to our actual experiences. They impose a mental processing system by which we make sense of and even twist these experiences to suit our preconceived notions.

The genius philosopher Wittgenstein devoted part of his life's work to quashing traditional philosophical thinking that falls into such a pattern. To quote a recent New York Times article on the subject:

..the non-empirical (“armchair”) character of philosophical investigation—its focus on conceptual truth—is in tension with [the goal of discovering actual truth]. That’s because our concepts exhibit a highly theory-resistant complexity and variability. They evolved, not for the sake of science and its objectives, but rather in order to cater to the interacting contingencies of our nature, our culture, our environment, our communicative needs and our other purposes.

Letting premade concepts filter our experience can inure us to authentic experiencing, compelling us into thinking that our experiences conform to those concepts. I believe that this is what makes people automatically assume that there is a god and that certain experiences are divine and must have had certain effects. It's what makes people believe in miracles that can happen any time they want.

The scientific-minded may just cite the lack of conclusive evidence for the occurrence of miracles, but this objection goes beyond that. It highlights how we, fundamentally, look at the world around us in an inauthentic way and why we are capable of seizing upon lies and integrating them into our reality. It demystifies what is at once an act of cosmic arrogance and wilful ignorance.

And the most egregious cases of this act are what I just can't stand anymore.

I was asked to write a piece on a new marketing concept called the 'multiplier' as an assessment for a job. What I wrote was probably not what they were looking for. Nevertheless, my scepticism towards it is the only worthwhile thing I had to add.

Here, I reproduce the piece in full.

---

As outlined by McCracken in a blog post, ‘multipliers' seem to not simply be a new breed of consumers but a category of people that supplants them. 'Multipliers' are not consumers in the traditional sense of the word. Creating an opposition between the two terms, McCracken contends that unlike with consumers, whose responses to products are "an end state", producers "depend on [‘multipliers’] to complete the work".

'Multiplier', however, cannot be a good definition for today's consumer as it seems to represent an attempt at looking past something that we as consumers will probably never leave behind—the act of consumption, with all its less-than-noble implications (or, in McCracken’s words, its “mischievous and sometimes malevolent intent”).

The idea of consumption is closely tied to the consumer-being, the Subject, and therefore also to his physical self. 'Multiplication' is orientated towards the Object, which is either a product or its value. Therefore, there are two inherent dangers in using the latter term: The first is that the term 'multiplier' objectifies the highly anthropocentric act of consumption and takes it entirely into the abstract realm of value, thereby inverting the relationship between Subject and Object; the second is that in abstracting the act of consumption, we would forget the physical and to some extent destructive nature of consumption. These problems are explained in turn below.

The Subject-orientation of consumption means that although consumers may sometimes build on a product they buy, in reality they do not ultimately do so to engage in the act of value creation. Consumers make consumption decisions according to their desires and goals. This means that even where they add value to products, they do so for their own purposes, which may or may not be to the producers’ benefit. For example, player modification of PC games for the benefit of other players is good for producers where it drives sales for the base products. Conversely, fan-made subtitles (fan subs) of Japanese animation often come with the original products for free, and thus many viewers, for whom the subs are a crucial access point to the products, need not pay for the products at all. These details would likely be lost with the term ‘multiplier’ or ‘multiplication’.

The second danger in using the term 'multiplier' is that we would risk forgetting the nature of the beast—of the physical, animalistic and often irrational impulse of consumption. 'Multiplication' makes it sound like a pure act of creation and would therefore belie the endless, insatiable and destructive striving that has come to be implied by the term 'consumption'. And thus we may forget the real costs that consumption imposes, whether or not any value was added in the process. This is not just in the context of finite resources; it is also relevant when the Object does gain mastery over the Subject, such as when the Diderot Effect (another area of McCracken’s work) takes hold and a new possession induces an avalanche of consumption.

All of these are nuances contained within the term ‘consumer’ that I do not see in the term ‘multiplier’. Making the latter the definition of today’s consumer would therefore risk sounding like a cynical marketing exercise that conveniently glosses over them. Caveat emptor.

Luck is superstition—at least when it suggests the existence of a god in the machine, a capricious supernatural force that determines one's fortunes. That said, luck could be a descriptive term, merely used in reference to circumstances that are perceived to be out of one's control. The first kind of luck, a prescriptive understanding of luck, should rationally be relegated to the level of superstition.

But what about the work of providence, or what people often call blessings? How much stock can we really put into that concept in our everyday lives?

It is convenient and perhaps sometimes truly beneficial to claim that, yes, one is specifically blessed in a particular matter. But here too a distinction needs to be made between a descriptive use of the word and a prescriptive one. A descriptive use could, for example, be meant to express gratitude. A prescriptive use of it would, however, go further in implicitly claiming, in a definitive way, that one is indeed personally helped by a higher power in a particular instance.

Such a claim probably stems from a desire to feel that one's every want and need is taken care of by a higher power, or that one has direct access to or a favour-based personal relationship with a deity.

I find such notions as presumptuous or childish as they sound. Our desires don't simply translate into reality. And if we accept that a higher power exists, and that this power deserves our devotion, the appropriate attitude would be subordinate our needs and wants to its will. Even trying to think up a win-win scenario strikes me as being arrogant and wrong.

However, just as many believe in luck as a metaphysical force, so do many believers subscribe to the idea that God blesses them in every human and banal matter that they are concerned with. I think that is a very simplistic expression of faith, one that resembles young children's belief in Santa Claus or in their parents' unfailing ability to grant their every wish. I think we need to grow up from such notions and learn to find faith that does not need constant reassurance.

I don't know if this has specifically been addressed by someone before, but one dimension to the existential problem is banality of existence. There is a kind of abstract meaninglessness that people like Camus have written about, but there's also a very practical sense of the banality that most of us are, from time to time, conscious of. In short: How do we live a life where we know that the world is so full wrongs and that we are, by and large, powerless to change it?

We live our lives day to day seeking our own happiness as though it carries a deep meaning. We suffer for the most trivial things, and we are put through all kinds of absurdity in order to buy ourselves some comfort in which we can pass our days. We lose, we gain; and after time has had its way, every joy or pain loses its significance. We live in bubbles, painfully focused on the minutiae of our lives but often unaware of the larger things going on around us.

And for our entertainment, we often watch others pass the same banal lives—characters on screens or on pages looking for happiness and revelling in frivolity. Or if we seek an escape, a fantasy, we try to lose ourselves in a world where individuals have power and could shape the world around them; and sometimes this only reminds us of just how unremarkable our own existence is.

Then there's religion or faith. But all it tells us is that, yes, we're powerless, that ultimately we need to depend on a greater power. It only gives an answer to the problem by affirming it and denying that we there is anything we can do on our own.

So how do we do it? How do most of us go about living our daily lives willy-nilly? It's strange, even fascinating.

Perhaps that is the miracle of life.