The mania about socialism has gripped America as the Obama administration reveals its true colours – mostly red, of course. A witty poster that has surfaced lately made a brilliant connection:

The Joker and socialism. Who would've thought of that? And Batman is Republican, of course. Heck, he used some crazy tracking device that looked it like it came straight out of the Department of Homeland Security. Commie Joker and holy Repub Batman!

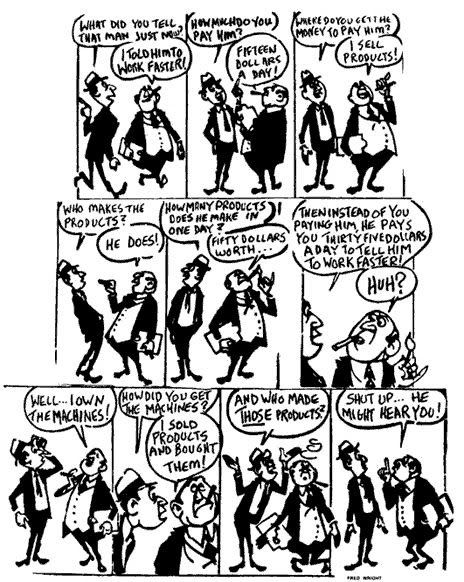

With every Joe Plumber screaming socialism whenever the Obama administration tries to expand federal regulatory powers, I decided to write a piece about socialism and what I think are socialist and what I think are not. Let me begin with an interesting cartoon:

That cartoon is very good because it encapsulates some of the fundamentals of Marxist ideas, which no doubt serve as the spring board for, if not the foundation of, socialism. So keeping it in mind, I shall offer my take on what socialism is about. It is broadly based on my own study of Marx's Capital, which is a key text in Marxist thought.

Marxism is a critique of political economy, and it is a radical one because it demonstrates ad hominem, or the characteristic of being directed towards the human subject. In Marx's words:

Theory is capable of gripping the masses as soon as it demonstrates ad hominem, and it demonstrates ad hominem as soon as it becomes radical. To be radical is to grasp the root of the matter. But, for man, the root is man himself.

Marx argued that the world of political economy is a topsy-turvy world, where economic categories and laws, which are created by man, have enslaved man and replaced him as the foci of socio-economic activity. And instead of the actual use that we have for the things we produce (i.e. focusing on our needs), we are much more concerned by how much they are valued relative to other things (i.e. focusing on the market and its operations).

This is commodification of things. Next comes the commodification of labour. Labour has a use – to produce commodities. It is bought and sold in the labour market. The value by which it goes (the wage) is not the same as the use value that the capitalist who buys it gets. The commodities that a worker produces are usually worth more in the market than the wage that the worker earns for his efforts. This creates surplus value or profit, which the capitalist enjoys.

Now, there are many reasons why this happens, and they are well covered by economics. But I contend that the Marxist critique still holds great truth. We are very focused on the intricate workings of the market, on the value of things when we exchange them, and we often lose sight of the thing behind it all – the man, who has needs, whose labour creates the commodities that are sold on the market. The subject without who nothing at all would matter because we cease to exist, since we are the subject ourselves or, failing that, because without them all economic activity would never have begun.

As I see it, a major contention is then on whether the capitalist plays a necessary role in economic activity. But even if we disagree on that issue, I think there is enough reason to pay attention to the rights of the average worker. What is the human world about but human beings? And the vast majority of human beings are not really capitalists – they still have to sell their labour to earn their wages for a living. And in this huge group of people we must include those who do not even earn wages but who, nevertheless, play important roles in human society: mothers/fathers, stay-home wives/husbands, unpaid social workers, students and children not yet in the workforce, etc.

Another big question is whether capitalism gives more than it takes. No doubt the world has gotten wealthier because of capitalism, despite the economic storms. But that is only to speak of the aggregate amount of wealth. Many people pay a heavy price each time the economy takes a hit due to man-made risks that they didn't personally take or have any control over. I think one of the things capitalism is about is rewarding risk-taking in the name of growth and development. But that should be balanced by the price that common people pay when things go awry. If risks must be taken, there must be something adequate for people to fall back on. Don't forget the common man.

I think that is the fundamental principle of socialism – the return to man. And this is why things such as universal healthcare, free or affordable education and minimum wage laws are pretty solidly socialist. Anything that violates or ignores this principle can hardly be called socialist, and things that are not necessarily based on this principle are not necessarily socialist. As such,

- Regulation is not necessarily socialist

And, by extension, neither is big government. Plenty of Marxists are libertarian in that they see government and bureaucracy as instruments for the entrenchment of the wealthy minority. They believe in the socialist principle like their statist cousins, but they are very wary of vast and powerful governing apparatuses that can be appropriated by certain interests, and which present a strong resistance to social change from the ground up.

Besides, regulation is also significantly present in regular capitalism, and especially in non-socialist systems that emphasize control, such as Fascism.

- Taxes are not necessarily socialist.

People all over the world pay taxes no matter what sort of system they live under, provided there is a functioning state and government.

- High tax rates are not necessarily socialist.

Any system of social organisation can introduce high tax rates or many forms of taxes. For example, popular discontent over excessive taxation was one of the problems feudalistic monarchies had.

- Labour unions are not necessarily socialist.

This might be more controversial. Labour unions are a very socialist idea, yes, but they can and have been hijacked by vested interests. The funniest ones are those whose leaders are appointed by the businesses whose interests they are supposed to keep in check for the benefit of the workers.

His focus is on Hope and Change, but, from the point of view of socialism, it's not very clear who has the hope or what change is in order. Most socialists would probably not count him as one of them.

I'm sure there are many more things that can be added, but this short list will have to do for this short write up. I hope, however, that I have provided a tool with which one can assess whether a policy could be regarded as socialist.

![]()