A while ago I talked about my scepticism towards concepts like Corporate Social Responsibility. While it's not nowadays considered nice or constructive to be dismissive of such things – we are dismissing all the good that do exist in the world, they would say – I think I gave a good enough explanation of why those are inherently absurd. But allow me to elaborate on it, with a view to what we can do. What I'm going to say might not sound new here, but I hope it's a coherent synthesis of the ideas I have expressed, delivered concisely at a particular angle of social commentary.

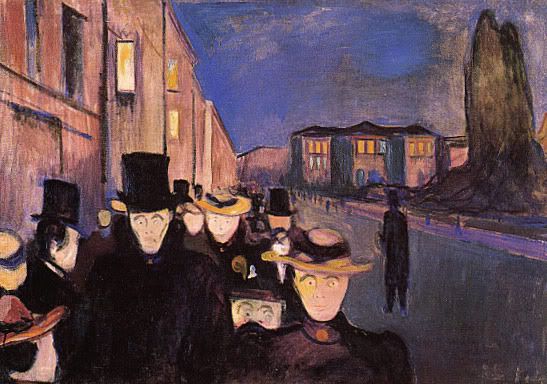

A few centuries ago, it might have been feasible to appeal to a traditional regard for virtues or a sense of honour and responsibility in the powerful – noblesse oblige, the responsibility of those who have. That was a world of stratified social relations based on feudal or patriarchal links. There were strong forces of tradition that prescribe relationships between a someone of higher rank and someone of lower rank, relationships generally involving responsibility and even compassion on one side and loyalty on the other. Appeals to the ideas associated with such traditions would thus make perfect sense.

Now, I'm not looking at history with nostalgic glasses. Of course, there were plenty of inherent injustices in the old stratified societies. What I'm trying to point out is the anachronism of a method with respect to the times.

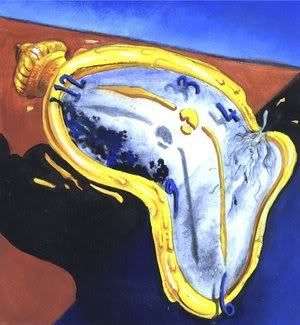

The rise of the classical liberals has destroyed the old forms of society. Social relations are no longer to be forged out of customs and slavish adherence to associated ideas. Rather, as Adam Smith suggested, they are to consist of mutual relations of self-interest. This is the bourgeois revolution. Fetters of tradition and its morality were to be removed to allow all men (and eventually women) to advance their own interests to a potentially unlimited extent. The rule of law is to be established to keep things in order, but no longer are people bound by prescribed roles and responsibilities. The only duty one owes is to the state, the embodiment of the social contract. But the rhetoric of loyalty and virtue that is still frequently used sits uncomfortably with the new direction of political philosophy. Strictly speaking, we have a duty to the state not because of some traditional moral concept or other, but because we are bound by the common interest in a stable society.

This arrangement sounds fine and well. However, the role of the state is still a grey area. We know why the state is there, but is the existence of a raison d'être enough?

In practice, the state needs to perpetually affirm its purpose and existence through its acts, which interfere even with our daily lives. A state that does not act is a state that no one has faith in; it is naturally one that will subsequently cease to exist. Some people might wish to say otherwise, but reality attests to the fact that the only viable states are states that act. And so what the state ends up doing is a matter of concern, and with it comes the question of its role and responsibilities.

The problem, as in the case of other legal entities such as corporations, is with the fact that the state is not a person. The state is a machine consisting of multitudes of individuals and bureaucratic apparatuses with non-human systemic considerations, likely controlled by certain interests that are themselves collective groups. The state has legally-defined responsibilities, but an appeal to its sense of responsibility or to its moral sense is useless. What you might expect to move a monarch or a lord is not likely to move a modern state with highly distributed powers, especially since it is constructed from relations of mutual self-interest.

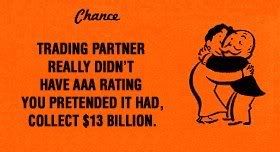

As such, appealing to morality – that might work on some individuals within the system, but it would be absurd to expect it to move the system as a whole. Chances are, that way, we will be hung out to dry waiting for our concerns to be addressed satisfactorily.

If we assume a system that is somewhat just, as Rawls does, relying on the state's legally-defined responsibilities would be enough. But I fail to see how a state that is, in reality, perpetually in the stranglehold of particular interests would ever realistically be just enough. We only need to look at the state of the world to confirm this: How many people remain hungry, poor and oppressed just because certain interests have to be kept satisfied, even in liberal democracies (keeping in mind, of course, the effect one nation has on another)?

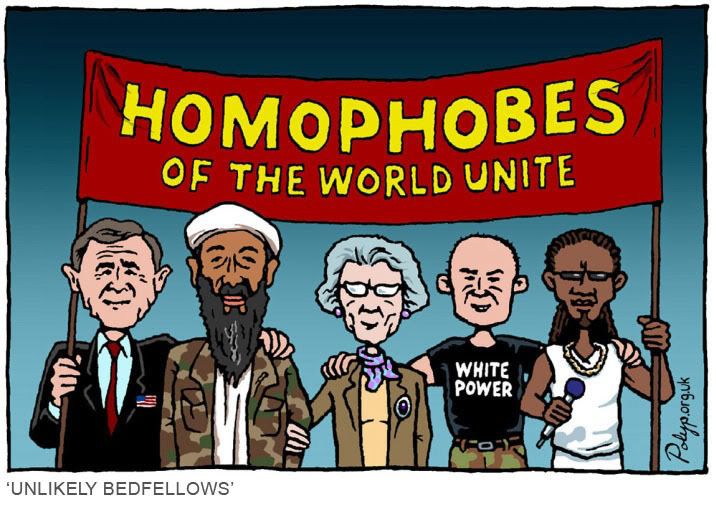

And, if what I have said so far is correct, the satisfaction of the concerns of those who are unjustly treated cannot be achieved merely by appealing to old concepts and traditions of morality. In a society built on mutual self-interest, you are pretty much responsible for advancing your own interests. This is why those who are oppressed must organise themselves as a force to fight for their interests.

But should they act only within legally-defined limits?

I believe that they cannot always do so. Ideally, we would want obey the law to preserve stability in the society for everyone's benefit. However, the resources at the disposal of the powerful make attempts to effect change through the prescribed channels very difficult. The playing field is far from level. Thus, it is unreasonable to expect us to only exercise our political freedom by voting in elections and appealing to our political representatives. We need other avenues, the most drastic of which is revolution. This is the practical argument for extra-legality. And since the same argument applies to the constitution, which is not necessarily just, extra-legality really amounts to extra-constitutionality.

Now, I do believe that the virtues are not completely lost. Otherwise, I could easily be construed as envisioning a world moved entirely by the force of might. However, in order to be able to appeal to them effectively, we have to take people out of their modern (liberal) institutional contexts. We have to appeal to human beings, the timeless individuals, not to citizens, soldiers or politicians. And this is the essence of the moral argument for extra-constitutionality – we do not adhere merely to the laws, but also to common moral concepts that hopefully have not died out. The moral appeal would strengthen the movement. However, before the movement can speak on such a level, it has to be able to operate on a level beyond the constitutional (i.e. in keeping with the practical argument). Otherwise, it would be trapped by the legal realist loop that smothers moral thinking.

In effect, what I espouse is a belief in the freedom to fight. Neo-liberals and free marketeers believe in free competition. But, as much as they might want to deny it, they are stuck within their own rigid systems. To be truly for liberty, we cannot advocate only a free market for products. We must advocate, above all, a free market for ideas and the political actions of individuals.

Conflict of interest is a circumstance of justice, and the lack of a viable conflict of interest in real life is an indication that something is wrong. A political system where we can only vote for parties with few differences between them is recipe for perpetual injustice. We must bring back other avenues of pressing for our interests, even if they are illegal. And we must appeal to human beings outside of the control of the modern state to fight in the name of what is good and just. This is the vision of justice as struggle and dialectics.

It is what it takes to strive for justice in the kind of society we live in.