Simplicity/sophistication

Posted by

moses

@

21:50

•

consumerism,

culture,

identity,

media,

psychology,

society

•

0

comments

![]()

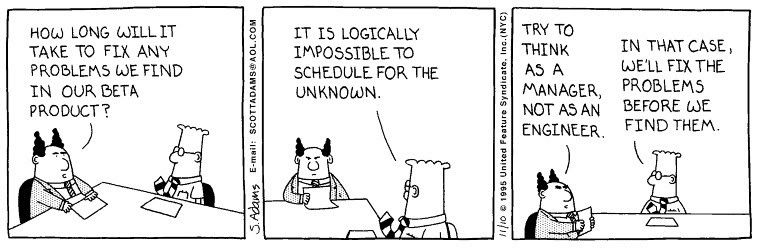

What is the simple life? Traditionally, it is understood as a thrifty life lived without pretensions. But what exactly does that entail? Are you thrifty as long as you don't buy yachts or mansions or don't live a jet setting lifestyle? Can you be free of pretensions even when you chase the latest trends and fashions?

How much to consume education?

Posted by

moses

@

15:44

•

economics,

education,

society,

United Kingdom

•

0

comments

![]()

Don't give up on English to oppose it

Posted by

moses

@

11:08

•

art,

culture,

identity,

Singapore

•

0

comments

![]()

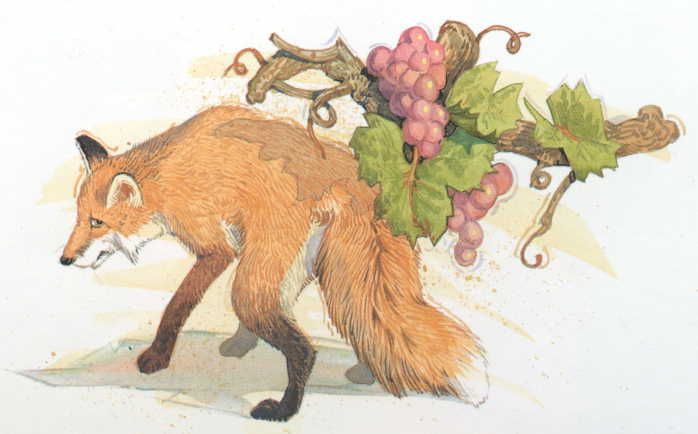

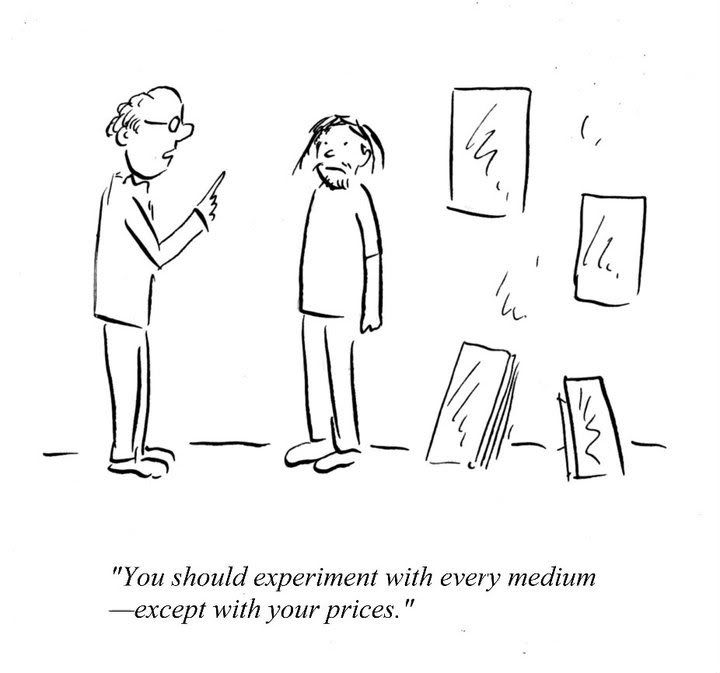

Art and its media

Posted by

moses

@

11:26

•

art,

culture,

philosophy,

politics,

society

•

0

comments

![]()

Education

Posted by

moses

@

09:56

•

education,

personal,

philosophy,

self help,

Singapore

•

0

comments

![]()

Every year it's the same. I would be lulled into thinking that there are possibilities here, that things will be different. This year, I actually convinced myself that I think positively now, that I will see things differently. I was even beginning to think that I may prefer to stay here instead of leaving again. But, in the end, I still feel the same way

The Commodification of Leisure, Part II: Mass Culture and Social Disorder

Posted by

moses

@

07:26

•

consumerism,

culture,

eudaimonia,

ideology,

Marxism,

media,

philosophy,

society

•

1 comments

![]()

Part I

I find it amazing how people get up in arms over criticism of their country. Some of them do not even care if the criticism holds some truth. That or they are simply convinced that it is false. Perhaps to them, their country can do no wrong. What is the source of such touchy pride?

I'd like to say that it's because these people are aware of the historical significance of their statehood, because they truly understand how it compares to the alternatives. But that is a distant knowledge, if it can be grasped at all. Rather, I suspect the source is found in 'education' and propaganda, in the meanings they imbue through symbolic power and in the paranoid alternative scenarios that they plant in people's minds.

It is patently ridiculous that the paraphernalia and icons of national identification are treated with such reverence, so much so that acts that indicate disrespect towards them may be subject to legal sanction. These symbols are said to have a unifying function, yet in affording them true iconic status, the real things that they might have stood for become overlooked, relegated into the obscurity reserved for complex ideas that seem difficult for the minds of the brash to hold.

Thus we have the flag, the lion and what-not, symbols that are regularly wheeled out to summon feelings of pride and attachment so the masses can cheer as they did for kings. These are closely associated with the conception of the nation, together with and sometimes more prominently than real things such as community and solidarity with your fellowmen. They are mere noise, the pop of party poppers and the drunken singing of anthems before the wars that kill citizens in the name of the fatherland.

Far from being its defender, the unthinking patriot who is swayed by these icons, by pithy calls to augment the glory of the nation, is a danger to the community. It is the patriot who gives strength to hegemony and oppression. In his blindness, he may allow all manner of evil and political deception to come to pass. What's more, he may play the role of a soldier and marshal for them, actively aiding them and coercing his countrymen. Hence, if there is one slogan that we must have for patriotism, let it be "Death to the patriot!”

Patriotism in peacetime is as useful as anger is while one is resting.

"We have discovered happiness"—say the last men, and blink thereby.This Nietzschean imagery seems particularly apt if we conceive of modern consumer society as the endpoint of a grand enlightenment project, namely that of turning human beings into masters of their own fates—beginning with mastery over nature through scientific progress (which is still ongoing), and arguably taken to the fullest extent in the Marxist vision of the human mastery over its own labour power.

This endpoint does not mark the fulfilment of the project, however. It seems that while science is still moving irresistibly forward, there is no longer much impetus to expand this project into other domains of human life. We have stopped, it seems, because life is good enough. Material conditions for the large middle classes in wealthier societies are sufficient for the pursuit of individual happiness; so what else do we need?

With the notion of success measured primarily in terms of the accumulation of material goods and perhaps influence, and now that pleasure as a chief mode of happiness is easily attainable, 'structural adjustment' is only used in a macroeconomic and financial sense. The drive for revolution dissipates in the humdrum of daily work and entertainment, drowned out by television and music. It's an uneventful and perhaps even blissful death.

Thus, it is perhaps the case that human agency can only, at least in present times, play but a small part in historical change. Mass action is generally precipitated by external changes and not vice versa. I think this certainly has implications on participation in social organisation, implications that are, unfortunately, less than inspiring.

The Culture Industry revisited

Posted by

moses

@

15:57

•

consumerism,

culture,

economics,

Marxism,

media,

philosophy,

society

•

0

comments

![]()

This vision is constructed through discourse that is sprinkled with an ever-growing list of newly-coined terms. Yet it is, at the same time, one that people can readily identify with—for who isn't ready to believe in the prospect of a brave new world, especially when the media has just informed them of the exciting new products available in the market?

Admittedly, Critical Theory does not often fare well in today's intellectual climate, a circumstance that I feel is attributable to its underpinnings in the labour theory of value, or at least in varying degrees of economic determinism. Popular conceptions of value no longer hold it as something objective or cardinal. Value is something that is purely relational and manifested in actual preferences. In other words, that people value something more than another cannot often be explained in terms of natural and tangible causes. Valuation is often a subjective affair.

In a powerful way, this undermines the Marxist critique of exchange value, not only by dispelling the labour theory of value on which the critique is based, but also by replacing the concept of use value with ordinal utility. Now we have another conception of value that is also Subject-determined and correlated with exchange value but is not equivalent to the latter. And the concept of use value seems cumbersome and obsolete beside one that is able to account for all Subject perceptions of value, including the intangible, instead of being mired in the materialist paradigm. Moreover, this conception of value is seductively democratic. After all, what can appear more empowering than a view of value that privileges people's preferences and decisions?

What this means for the Frankfurt School critique is its effective isolation as an elitist view of culture that presumes to tell people what they ought to value. If preferences are subjective, what right does anyone have to proscribe any as long as no actual harm can reasonably be alleged to result?

It is difficult to defend the Frankfurt School from such a charge. Yet I maintain that its critique of the Culture Industry still rings true, albeit in a way that may necessitate some distancing from Marxist discourse. My proposition is to look at the critique from a particularly modern perspective that revolves around expectations and hype.

If there is anything that we have learned from the last global financial crisis, it is that expectations may diverge from a more tangible reality of a situation, whatever the latter may be. Perhaps this can be seen in terms of the divergence between short-term and long-term confidence, the latter which is dependent on a stricter or more complete procedure of reasoning. But regardless of what exactly we should compare expectations to, the evidence seems to point to the existence of hype.

Hype can be understood, in that sense, as the inflating of expectations of returns relative to a more tangible measure of actual returns. Even under conventional ways of looking at the market, hype is rarely a good thing—it implies that buyers are ultimately losing out in terms of expected versus real returns to their spending. And since hype is paid for by marketing costs that are likely to figure in pricing decisions, hype also represents a potential deadweight loss.

What does this have to do with the Culture Industry? It is my contention that the Culture Industry is a major source of hype. It deals in feelings, manufacturing them in order to generate interest in things—a process that is typically subsumed under the goal of making profit. It thus becomes the primary source of trends that influence people's preferences in goods. To grasp the commercial importance of the Culture Industry under late capitalism, simply witness how advertising thrives on the products of the Culture Industry.

Moreover, this principle does not apply merely to the products of various industries, but also to more general things such as lifestyles and even happiness—the message is that spending our money on something or adopting a certain attitude or lifestyle can bring us happiness or a sense of fulfillment.

But can hype not become real if it proves to be permanent? After all, there are still many people who would be very happy to buy, for example, the latest Apple products simply on the basis of the expectations that have been generated through marketing. Thus, it would seem to be the case that these people continue to get what they expect.

Yet it remains true that no one really knows how long the ephemeral expectations that are associated with hype can last, especially on the level of the individual. All it takes is for the realisation to come, in one fine moment, that there is no basis for believing that something is as good as it has been made out to be. Much of the perceived returns would be lost in that moment, just as the perceived values of certain financial instruments evaporated a few years ago.

The lie that Culture Industry sells us does not, therefore, have to depend on a highly contentious philosophical analysis of value. Whatever the exact nature or typology of value may be, hype as the commodification of feelings can be observed in our everyday experience; and it stands clearly a means of extracting profit through the inflating of expectations.

Those who wish to hold on to dreams should also be prepared to give them up. One cannot be uncompromising about dreams, for dreams have power over us. They have the power to reveal our mortal limitations, unclothed by the delusions of power that flights of fancy bring. For dreams are always a few steps ahead of us—the more we are able to realise, the fancier they become. Confidence often leads to our undoing, and the moment when we see the precariousness of our situation, the potential futility of our efforts, is the moment of despondency; a moment of lifelessness and regret for failures past.

Gatsby believed in the green light, the orgiastic future that year by year recedes before us. It eluded us then, but that's no matter—tomorrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms farther… And one fine morning—

So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.

Big picture, small picture—who the hell knows anyway?

Posted by

moses

@

20:18

•

philosophy,

politics,

pseudoscience,

psychology,

society

•

0

comments

![]()

A note on the elections and on change

Posted by

moses

@

12:17

•

culture,

politics,

Singapore,

society

•

0

comments

![]()

The Commodification of Leisure, Part I: Art and the Culture Industry

Posted by

moses

@

18:35

•

art,

consumerism,

culture,

Marxism,

media,

philosophy,

society

•

0

comments

![]()

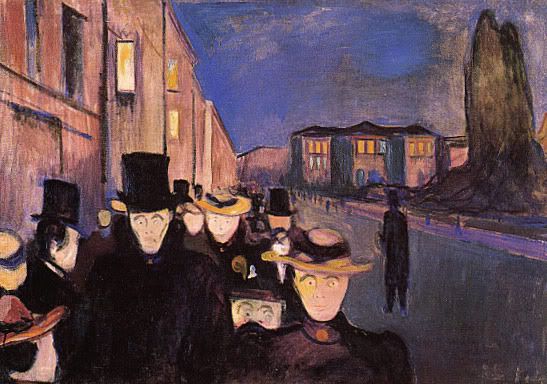

Here I present a reading of Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer's The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception, with reference to Frederic Jameson's essays on Adorno in Late Marxism and Amresh Sinha's Adorno on Mimesis in Aesthetic Theory.

Roland Barthes asserted, mirroring Adorno's critique of pleasure, that mass-produced culture under late capitalism serves to conceal or obscure the capitalist mode of production, thereby eliminating resistance. However, this line of argument is once again susceptible to the criticism, born of audience studies, that audiences are not simply passive recipients. Indeed, I think the exact opposite is the case: Far from hiding it, the Culture Industry revels in the capitalist mode of production, showing us the promises that await us should we acquiesce to the system, namely all manner of consumer goods and the status and identities that come with them—rewards that are, however, readily available. It tempts the audience with these prizes, rather than compelling or co-opting them directly. But, crucially, it also promises the more elusive, yet-to-be prospect of success itself, embodied most vividly and blatantly by the stars it churns out as the human end-products of its capitalist mode of production. It is therefore unsurprising, though ironic in light of Adorno's linking of pleasure to readily achievable ends, that audiences are so preoccupied with stars.

Continued in Part II

The Subject of Pipe Dreams

Posted by

moses

@

18:38

•

identity,

Marxism,

media,

philosophy,

politics,

society

•

0

comments

![]()

On the relative unimportance of the relativity of truth

Posted by

moses

@

18:02

•

ethics,

philosophy,

politics,

society

•

0

comments

![]()

I wonder how often the pronouncement that "It's all relative anyway" is accompanied by the knowledge of why exactly that is so. Perhaps utterance without precise understanding is somewhat apt within a relativist paradigm. In any case, it would certainly be apt to draw upon one philosophical tradition, which grounds beliefs on a particular theoretical basis, in order to explain and mitigate the notion that truth is relative. Hence, I want to look at structuralism and its take on the crisis of foundationalism.

Politics as tacit knowledge

Posted by

moses

@

18:12

•

media,

philosophy,

politics,

science,

society

•

0

comments

![]()

The Harvard professor who was dead wrong about the North African/Middle Eastern political upheavals comes to mind here. Yet we still see experts coming forward to offer their expert opinion on this very topic, even as events are still unfolding. It might not matter so much if they were merely at risk of being wrong, but they are also party to the framing of the present struggles of real people as political theatre, as a spectacle for entertainment or as a commodified platform for making a point. And these experts congregate or belong altogether in the media, eager to broadcast their messages to a wide audience partly because this may further their careers.