There are some things that are perhaps confusing or seemingly very contentious in what I wrote about last. Therefore there is a need to qualify it or, more precisely, to delve into the unspoken claims behind some of the statements made. Most importantly, I think, I must talk about my perspective on choice, freedom of choice and the critique of choice.

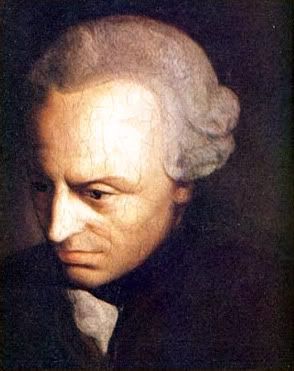

I've written some time ago about the ability to question the choice of others. I argued that the sovereignty of the subject is illusory, since choices are often externally induced rather generated by an authentic individual will. I should add that whether there is such a thing as authentic individual will does not pose a problem to this view. In fact, if there is no such thing as authentic individual will, if choices are therefore entirely a matter of persuasion, all the more it should be possible to legitimately debate subjective choice.

There are two new things that I want to bring up here: Firstly, I want argue for the existence of general or common conceptions of what constitutes bad choices. Secondly, I want to question the non-invasiveness of subjective personal choice.

Some might disagree fiercely that what I consider bad are truly bad in any objective sense. Some might go on to say that there is nothing objective about taste. I'd like to question this last statement. Indeed, my position stems from my scepticism regarding absolute relativism even in the notoriously personal and subjective realm of tastes.

As such, I'm not so much positive of the existence of one correct theory of the good as I am sceptical of the notion that people cannot commonly share certain conceptions about what is bad. It may be impossibly difficult to find a general enough conception of the good with which we can objectively judge all choices, but it's a lot easier to find general ideas about what is bad with which we can legitimately argue that certain choices are bad.

This is a lot more obvious for choices with real material, physical and psychological consequences, but if we can establish this in the realm of tastes, it's probably safe to say that it's a solid claim. Are there instances where people commonly regard certain cultural products as lacking in quality? I think so. When I talk to people about reality TV shows, for example, I find that many would admit that certain shows are "trashy" or "bad", even if they admit to having a 'guilty pleasure' in watching them.

Perhaps this is too anecdotal, and perhaps there is a correlation between such sentiment and education level or class. However, there is still something to be said about this phenomenon.

Firstly, this implies that pleasure and people's conception of the good do sometimes diverge. Thus, it seems to contradict the central thesis of traditional hedonistic Utilitarianism, which is ironically a very popular mode of thinking. As such, good and bad is not merely a question of what consequences a choice brings in terms of utility or pleasure.

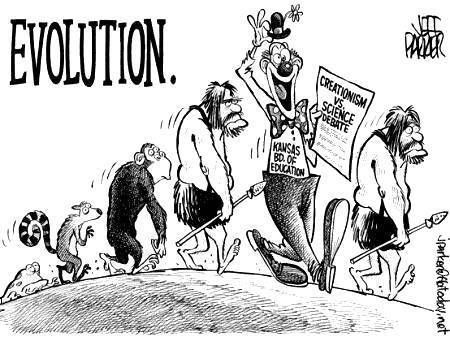

Secondly, though one might convincingly argue that common perceptions on what cultural products are bad could simply be explained by the fact that people have been told by the 'experts' about what could be considered good and what could not, all is not lost. At first glance, this may seem to corroborate the notion that nothing is objective, that what seems objective is simply the imposition of a subjective viewpoint. Yet, no matter what we think of some of those 'experts', there tends to be a process of discourse that generates and moderates the opinions offered within serious critical analyses of cultural products. Discourse, whether it is realised through an actual debate or through the influence of intellectual traditions that play off one another, lends criticism credibility as something greater than simply a collection of individualist subjective viewpoints.

Therefore, it might be that what is considered bad is something whose merits cannot be seriously analysed and discussed. Hence, it is mostly examined, if at all, merely as a symptom of a cultural trend, tending on its own to fall outside the process of discourse. What is good is a question that is debated, perhaps endlessly, in the discourse, but what is bad simply falls outside of it. The reverse is not true; what falls outside of the discourse is not necessarily bad. However, at least we now have somewhere to begin in deciding what is bad—by asking why some things don't come up in serious discussion on their own merits.

This is a bold argument, and it might come off as some kind of intellectual snobbery. But I would add that it's not necessarily a sin to enjoy something simply for any kind of pleasure that it gives. The problem is when the vast majority of what is offered can only be enjoyed in terms of the overt pleasure that it brings. Thus we come to the issue of the invasiveness of subjective choice.

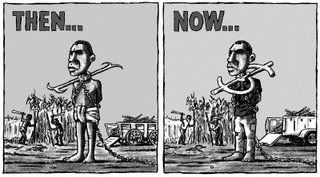

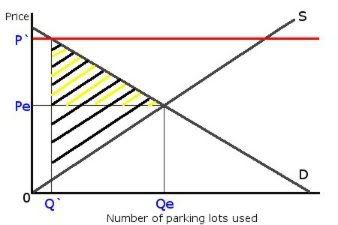

If you want to do business, half the job would be done for you if you appeal to what people want. Does this mean, however, that consumer choice is paramount in production and marketing decisions? In fact, the very nature of marketing is antithetical to consumer choice. But the power of capital is not so much in forcing you to consume what you do not want, but in making you consume what you want all the time and, in the process, making you want to consume associated products as well.

Thus, the companies appeal to the lowest common denominator in order to increase sales. And they do not let your attention wander, for the sales of other cultural products and physical goods, upon which billions of units of exchange value ride, depend upon your near-undivided attention.

This is how capital imposes a near-monolithic culture on our tastes, by giving us what we want, but on their own terms and hindering our ability to emancipate ourselves from the pre-determined choices that we as consumers and members of modern society are expected to make.

But the burden of creating these circumstances does not lie on inhuman capital alone. In continuing to make the same kind of choices, we are also guilty of imposing on society a narrow range of tastes as the determinant of the cultural products that are available. Hence, our subjective choices are invasive in that, collectively, they deny other people and society at large choices that are emancipated from the dominant cultural milieu, while at the same time bulldozing through any question of quality in favour of focusing on the levels of pleasure obtained from cultural products.

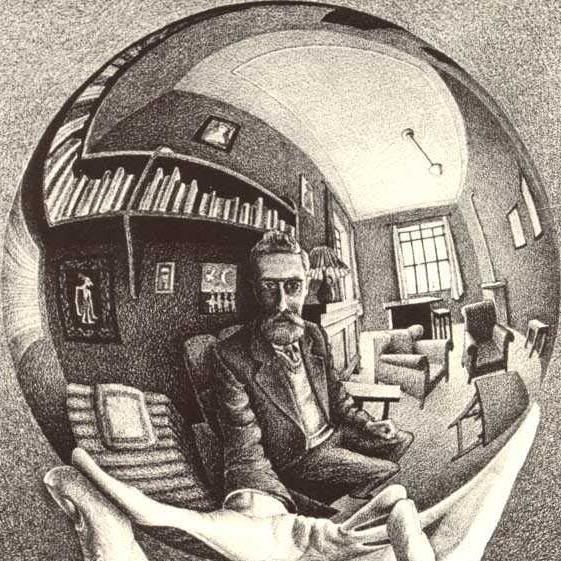

Hence, like slaves who have never apprehended the notion of freedom or like the benighted denizens of Plato’s cave, we perpetually choose to live within the same kind of paradigm, not knowing what else lies outside of it, including things that convincingly possess qualitative value. The market may give us choices, but as long as we are unable to escape the paradigm of pleasure, we know that we are still fundamentally unfree.