Wow, I can hardly believe this. Check out what Prime Minister Lee had to say to students: It is not all about grades, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong told undergraduates at the end of a dialogue on Tuesday. They should also be charged up about other issues and causes, like their counterparts in the United States, India or China, he added.

'If you look at the best students in dynamic societies such as the US, India or China, they are not just bright, they are passionate, idealistic, driven, out to change the world for the better and to make a mark for themselves.'

However, what will make the difference is when Singaporeans live overseas and are exposed to a different environment, he said. 'You see how other people live, and you cope with the different circumstances, and from that we hope you get new tools in your toolbox to solve problems.'

Somehow I really doubt they'd like protests and rallies much. A half-hearted attempt at change as usual? I guess so.

But, hey, why not try, right? So let's look at the ways through which we can participate, starting from the running of our daily lives.

I'm just going to focus on one aspect (but lessons for some others can be drawn from it), since a related issue has been around for some time: How to exercise some rights in the face of a private company's monopoly on a public service.

Consumers don't like monopolies for obvious reasons. They are price setters and might severely reduce the consumer surplus and create deadweight loss since they are producing at far below the Pareto Optimum in order to maximise profits. Economic jargon aside, I think all of us can at least intuit that monopolies can get away with doing things like setting much higher prices due to the lack of competitors.

So what happens in the case of a natural monopoly, where the set-up costs or any other barrier to entering the market is so high that there can only be one effective provider of a service? The government should then step in by nationalising the company, subsidising it or setting price controls to safeguard the interests of the public. Which measure is taken might depend on how vital the service is.

Unfortunately, the price isn't the only aspect where the public stands to lose when a vital service is run by a monopoly.

The private sector can get away with many things the public sector can't. Racial discrimination, for example, is not nice, but private companies reserve the right to not serve anyone for any reason. Your influence as a consumer in a free country lies in your ability to take your custom somewhere else. If a company is given to bad practices, they lose business. Simple as that.

This understanding is probably as entrenched in Singapore as in the USA. Some countries favour regulations to restrict bad practices, but Singapore has a 'one of the freest places to do business in' reputation to maintain, right?

But what happens when it's a monopoly? You can't take your custom anywhere else. You can simply not buy the service at all, but you don't really have a choice if it's a vital service. And – I'm getting to the issue itself – public transport is vital service.

SMRT has seen fit to enforce absurd restrictions on the consumption of food and drink within its vehicles and premises. Fair enough, many people might think. But as I've mentioned before, they've gone to such lengths as to fine someone for having a sweet in her mouth.

I've personally been told that even drinking plain water is not allowed. So they're saying that if someone feels dehydrated, she is not allowed to hydrate herself with good ol' H2O on their property? Even if the water spills, how much trouble would it be to clean up a small puddle of water, if needs cleaning up at all? Can you imagine telling your guest that he is not allowed to drink even plain water in your house?

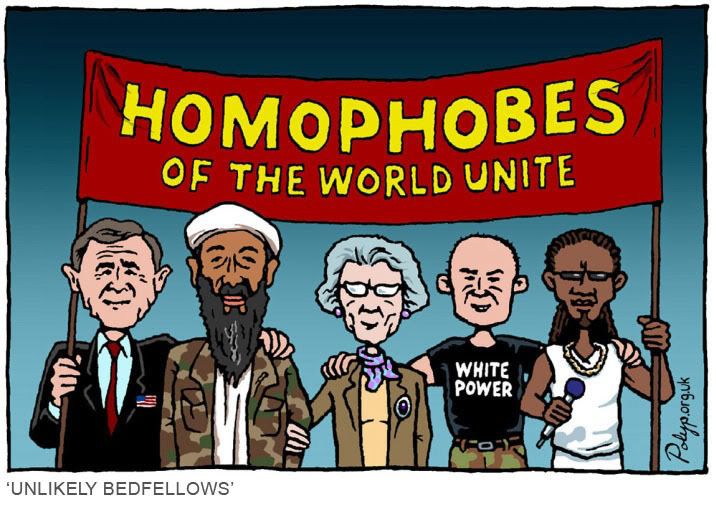

Here's a tip: There are rules, and there is crazy enforcement.Some things just aren't worth enforcing to such an extent if you don't want to be a major jackass. The government seems to know this sometimes, as shown by its present stance on 377A. SMRT doesn't.

Maybe it's not that big a deal, but its attitude constitutes giving bad service, especially since they can charge you a significant amount of money for a trivial thing. Money-making scheme much?

And despite public criticism, it has persisted with the practice. This is good evidence that it knows it's in a position to not have to back down on things, unless the government intervenes, which it probably won't do because again Singapore needs to promote business freedom.

And SMRT can do this because it's a monopoly facing an inelastic demand curve as a vital service provider. You still have to take its trains even if you don't like its policies.

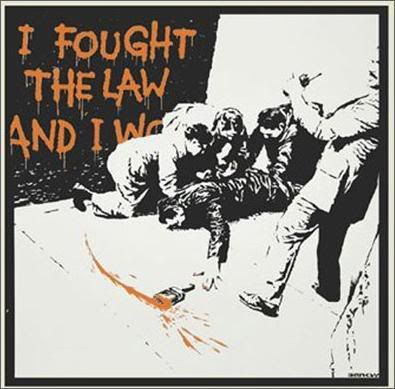

I really dislike the idea of bending over for such companies. Many people don't either. So this is how you can exercise some rights: Flout the rule.

Oh, no, but that's bad or illegal!But in what other way can we resist? When Rosa Parks flouted the rules, was she wrong? This is the concept of civil disobedience – when you have no say, you refuse to obey.However, although civil disobedience is meant to be visible as a political statement, I'm not suggesting we make martyrs of ourselves. It's not worth it to have to pay fines for stupid reasons just to make a statement that might not change anything, given the way things work here. Instead, we disobey quietly. Go on with eating and drinking simple things when the staff isn’t watching. It's not that difficult.

We make our actions visible as anonymous individuals acting in concert. They'd probably know that they can't stop people from doing it when they're not looking. Maybe they will let it go. Maybe they will continue and look like idiots. Maybe they will attempt to stop it with more ridiculous measures that would make the issue more manifestly absurd in the eyes of the public and draw increasing and harsher criticism. It's a lose-lose situation for the company.

But maybe the best thing is for their measures to actually be counter-productive. Instead of helping to maintain cleanliness and reduce costs, their anal-retentive policies should actually make their property dirtier. It would probably make them rethink their position.

To that effect, let's surreptitiously but intentionally spill stuff like soft drinks and create all sorts of mess when we can. It's time to punk a company that thinks it has free rein.

This is how we resist. This is how we learn not to take it up the ass because we have no say.