Is all fair in love and work? I think many would say no, and that is partly because of a difference in attitudes that is entrenched in our culture and in our discourses on love and work.

Consider this: Well-known columnist David Brooks wrote in an article for the New York Times that young people should not "pursue happiness and joy" when deciding on their career paths, focusing instead on solving the problems they come across and seeking fulfillment through "[engaging] their tasks". On the other hand, Brooks wrote in his book The Social Animal that "The relationship between money and happiness is very tenuous; the relationship between personal bonds and happiness is incredibly strong". So we are told that happiness matters in our personal relationships but not in our jobs.

But why this difference in attitudes? How much time do we spend at our workplaces every day versus the time we spend socialising? How many friends do we see every day for durations that come anywhere close to the amount of time we spend at work? Why does happiness not matter in something that forms a significantly larger proportion of our everyday lives?

The only relationship we have with people that can come close in terms of the time and commitment that we have to invest in it is a serious romantic relationship. We might say that it's difficult or even unbearable to be in a serious relationship with someone you don't love, having to see the person daily and to pretend that, deep down, you care about him/her first and foremost. So why do some us think we can do it when it comes to our jobs?

As we are probably well aware, it comes down to a difference in motivation. It's not that happiness matters in our personal relationships and not in our jobs to begin with, it's that a lot of the time we look for happiness in our personal relationships but not in our jobs. That is quite understandable. Work occupies that space between our public and private spheres of life where necessity and practical considerations are dominant. In other words, the primary reason we work is to earn a living, and we don't often have much of a choice in that.

But, that said, we can still ask why we voluntarily set up a teleological barrier between work and personal relationships. Why do we judge people who enter into personal relationships out of purely material concerns? Why are people who work purely for money normal but those who seek partners for material reasons deplorable?

You might put this difference in attitudes down to a matter of frequency and significance. Serious relationships are more significant because they are harder to come by, whereas one can switch jobs relatively easily. But what difference would there be if we keep looking for jobs without putting much weight on how much we love them? Working for purely practical reasons wouldn't therefore be a temporary arrangement.

Or you might put it down to a matter bad faith. Normally, people enter into personal relationships on the understanding that it is mostly, in a strict sense of the word, personal. In other words, as we see it, personal relationships concern our persons and not so much external and material things. So in letting the latter take precedence, you would often be breaking a tacitly made contract.

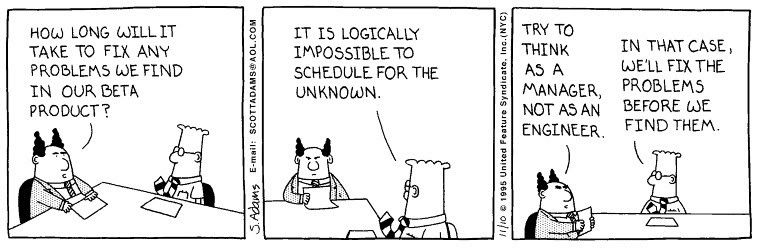

Yet these days many jobs ask for passion and a degree of personal commitment that justifies the personal sacrifices that we have to make for them, often for no tangible compensation. We can no longer be assembly line workers who perform mechanical tasks while waiting for the working day to end so that we can be free to live our own lives after that. The discourse on work-life balance is increasingly making way for the discourse on work-life integration. The job is no longer something that you have to get over and done with out of necessity; it's very much a part of you as a person. Indeed, it demands to be so. Hence, if we put on a front in our jobs, aren't we similarly lying to our employers and maybe to ourselves?

So, in light of the changes in the way we live and work, is the sacred teleological divide between jobs and personal relationships defensible? Can we condemn people who treat love as labour, as an exchange to be understood in material terms? If we can lie and pretend that love or passion for our jobs is integral to our work ethic, why should we disapprove of people who pretend that love or passion is integral to their relationships? Are we just being hopeless romantics who wish to use moral indignation to protect one of the last aspects of our lives that is not touched by the paradigm of commodity exchange?

Ma Nuo, a Chinese reality show contestant, was famously blasted by the public for stating on the topic of life partners that she "would rather cry in the back of a BMW than laugh on the back of a bicycle". But wouldn't many of us rather cry in the back office of Goldman Sachs than laugh behind the counter of a café? What makes us sure that that is a morally superior sentiment?

So perhaps we can't judge people who enter into personal relationships for material or tangible gains any more than we can judge people who work purely for money. At this point, that seems to be the most logically consistent position we can have.

Can an immutable law be, at the same time, constrained by context and dependent upon particular circumstances for its construction and application? I think so. To put it simply, a law is made real insofar as it is known and obeyed, and its construction and application is dependent on the societies (and on the particular moments in their history) that institute it and that are governed by it. Yet the same law may have the gravity and the force of an immutable law.

But it is not my intention here to discuss the metaphysical implications of this line of reasoning. Instead, I want to take a brief look at a pillar of Kantian ethics, which is the notion of autonomous will. As my memory of Kant's first two Critiques is sketchy, I am indebted to the SEP in writing this quick recap of Kant's moral philosophy.

Unlike the utilitarians and many other ethical systems, Kantian ethics holds that moral law is constituted not by instrumental principles that rational agents must adhere to in order to attain some form of ultimate good. Rather, moral law is founded upon the categorical imperative, which is a non-instrumental principle and which is not predicated on the existence of an abstract notion of ultimate good.

Nor is morality the product of our physiology. Unlike the central principle of, for example, an ethic that is based on empathy for others, the categorical imperative does not command us to act by virtue of what we feel (although emotions may play an important part in motivating us)—it commands us unconditionally.

Hence, we have a duty to obey the categorical imperative. But not all duties are absolutely binding—the law of the land, for example, is only binding insofar as we fall under its jurisdiction, a status we can often opt out of by leaving. The duty to obey the categorical imperative is, on the other hand, absolute because it is binding for all rational agents who are by definition "capable of guiding their own behaviour on the basis of directives, principles and laws of rationality". And we cannot opt out of our membership in the category of rational agents.

We can therefore see the connection between the categorical imperative and our status as rational agents. But the notion of autonomous will has not yet entered the picture. What role does it play in Kantian ethics? We are tempted to assume that rational agents possess autonomous will, which is a point that Kant does argue for. But how does he do so? And how is this important to the categorical imperative?

As rational agents, human beings possess rational wills, which is a will that "operates by responding to reasons". Hence, for it to be rational, it should not be entirely constrained in its operation by, for example, "being determined through the operation of natural laws, such as those of biology or psychology". To some, this might seem like an attempt to divorce reason from our biological make up, which they would regard as labouring in vain under the idealist illusion. However, Kant does not seem to go so far. He argues only that what is necessary for a will to exercise itself freely is "the Idea of its freedom", holding that having free will means not strictly operating under the constraints of immediate practical considerations when "trying to decide what to do" and "what to hold oneself and others responsible for". In other words, as I understand it, we can be said to have free will because in our practical endeavours we are capable of engaging in "self-directed rational behaviour and to adopt and pursue our own ends"; we are capable of making choices and not just of doing as the physical or material circumstances dictate.

Thus, Kant asserts that rational wills are also necessarily autonomous wills. And the significance in his ethics of the autonomy of a rational will can be found in the Kingdom of Ends and humanity formulations of the categorical imperative. Under the Kingdom of Ends formulation, a will that regards itself as a member of the category of rational wills must "regard itself as enacting laws binding to all rational wills" and thereby as a member of a “systematic union of different rational beings under common laws”—a “Kingdom of Ends” whose members "equally possesses this status as legislator of universal laws". Hence, not only must we acknowledge other people as fellow rational, autonomous beings, we must also recognise that they possess the same responsibilities as we do because they are similarly, in their capacity as rational and autonomous beings, capable of enacting universal moral laws. This is a strong basis for the concept of human dignity, a concept that is articulated in the Humanity formulation of the categorical imperative, which demands that we treat others' humanity not as a mere means to our own ends but as an end in itself.

What this means, in plain language, is that we must respect fellow human beings as equals who, like us, possess a significant basic level of dignity. This is a law that should appear immutable to us as both its legislators and its subjects; it should not be modified depending on who we're talking about or on the prevailing circumstances. Even those who are guilty of heinous crimes retain their humanity and therefore their human dignity, and the punishment meted out to them should not fail to recognise this.

All this might seem quite obvious when we think about it, but when we feel antipathy towards others for the smallest of reasons, we clearly need to remind ourselves why we shouldn't our feelings cloud our reason.

Singapore 21

Posted by

moses

@

06:44

•

#occupyrafflesplace,

Asian values,

big business,

consumerism,

economics,

education,

freedom,

GINI,

politics,

Singapore,

socialism,

society

•

2

comments

![]()

Singapore is a bit like a child who was bullied and looked down on by its peers—it grew up having something to prove.

The insecurities of Singaporean society are a reflection of the insecurities of its founding fathers. And as all deep psychological traumas go, the result is a pathological pattern of behaviour—in this case, the perpetual post-Separation obsession with proving that it can prosper without natural resources and an initial industrial base.

To this end, Singapore has transformed itself into a rentier state in all but name. And the resource that is rented: Human labour. Factories and offices in Singapore are in principle no different from the sweatshops of the Third World, riding on loose or non-existent labour laws and wage legislation that help make the country competitive as a magnet for foreign investment. Politically, in order to facilitate this path of economic development, security and stability have been prioritised over other goals such as democracy and social justice—again, much in the manner of the archetypal rentier state.

What sets Singapore apart from other rentier states that rely on renting its workforce to foreign investors is the kind of industries it seeks to attract. Thus, a significant part of the workforce has to be trained and educated enough to do the kind of work that those industries require, but not in a manner that is enough to enable them to challenge the country's socio-economic trajectory.

That is the essence of Singapore's famous economic and political pragmatism.

However, popular dissatisfaction with its immigration policy and with falling standards in the provision of public services point to a parallel but related trend in the country's political and economic stance.

Even the most diligent of workers may not be able to stomach the fate of forever being a mere cog in the economic machine. Hence, as a form of compensation for their dedication to the government's vision, citizens were promised comfortable middle class lifestyles that were ensured by the provision of subsidised high-quality public services. This is one of the reasons why the government has invested heavily in the country's healthcare and transportation infrastructures—things that are, incidentally, important in maintaining the productivity of the workforce.

This social compact has held until fairly recently. As Singapore increasingly aligned itself with the neoliberal paradigm, however, the old wisdom of labour market liberalisation—which also happens to be a core tenet of neoliberalism—was eventually joined by the move towards the privatisation of state-owned enterprises.

With this move, naturally, came an increased emphasis on profitability, which has been blamed for the fall in service standards in the country's public transportation system, as demonstrated by the recent and unprecedented major disruptions to urban rail services. At the same time, fares continue to increase, which only helps to lend credence to the notion that the privatisation of public transport has not been in the public's interest.

In addition, as an extension of its stance towards the labour market, Singapore is importing large numbers of cheap workers in its continuing effort to keep labour costs low, thereby contributing to overcrowding and adding to the stress on the country's infrastructure.

Thus, Singaporeans can no longer expect the nanny state to take care of them. Now, all we get in return for our hard work and dedication are promises that are no longer backed by concrete socio-economic support structures. We may have been a first-class rentier state before, but now, with increasing income inequality and decreasing welfare, there is less and less to separate us from the neighbouring states we so enjoy looking down on.

Can things change? Perhaps with the aid of the vast sums of public money that is currently given to the government's investment bankers with little or no public oversight. Will things change? Probably not if we are counting on the old guard to make it happen.

Unfortunately, at the rate we are going, change probably won't come soon enough. Add in the uncertainty in the global economy and the prospect of slower growth, and you know we're in for a rough ride.

So, in light of our predicament, let me say this: Welcome to the 21st century, ladies and gentlemen. The worst is yet to be.

So, in light of our predicament, let me say this: Welcome to the 21st century, ladies and gentlemen. The worst is yet to be.

You vs. the world

Posted by

moses

@

09:26

•

adulthood,

optimism,

personal,

pessimism,

self help

•

0

comments

![]()

When cornered, many animals fight back. We should probably do the same. Compromise becomes impossible when there is no middle ground. The only options are capitulation and confrontation, and at times only the latter offers a chance at survival.

When people talk about confronting an issue or a problem, they sometimes mean capitulating to it. Catchphrases like "change your mindset" or "adapt to the situation" may conceal a sense of helplessness that has prompted the speaker to give up without actually admitting as much.

Indeed, surrendering may often seem the easier option. Sometimes, the world seems hostile to our ideas and our aspirations; sometimes, it defeats us. However, even if we haven't lost, it's so much easier to give up without a fight. Let the world consume us rather than resist it. After all, isn't defeat inevitable?

It's true that, chances are, going against the world will be a tough long slog. And you're often alone in that struggle. But it may be your only chance at achieving freedom when everything conspires to bind you. The more remote the possibility of compromise, the more you have to fight.

If we do choose to fight, we shouldn't expect to survive, much less to win. But perhaps, by the time we are done fighting, a path towards compromise would have opened. Or perhaps we would indeed have to surrender in the end. But you will certainly never find out for yourself if you give up from the start.

And that I think is a fitting message to think on as the new year rolls around.

Simplicity/sophistication

Posted by

moses

@

21:50

•

consumerism,

culture,

identity,

media,

psychology,

society

•

0

comments

![]()

What is the simple life? Traditionally, it is understood as a thrifty life lived without pretensions. But what exactly does that entail? Are you thrifty as long as you don't buy yachts or mansions or don't live a jet setting lifestyle? Can you be free of pretensions even when you chase the latest trends and fashions?

Of course, the simple life, in the traditional sense of it, still exists. But in the developed part of the modern world, it is increasingly rare. In everyday life, the urge to consume—to spend and to be wealthy enough to spend—is overwhelming. Through constant exposure to various media whose function is to encourage consumption, we have been conditioned to desire and even need extensive material comforts.

Consumption is also about status and a social-psychological need to earn one's place in modern society. Simply being able to consume and being 'sophisticated' enough to know how to consume confers upon us identities that are compatible with the self image of modern society. And what falls outside of the latter is at best unconventional.

Thus, society exerts a pressure on individuals to conform to a consumerist lifestyle, and this pressure increases as more and more people embrace that way of life. Mass exerts its own gravity; popularity may well correlate with conformity.

One result of this trend is the engendering of a pervasive inertia among the expanding middle class—we have become much more productive over the past century, but most of our time and energy goes into the furious cycle of production and consumption, leaving us perpetually exhausted and, in our spare time, desiring only to enjoy the material comforts that our labours have bought. So despite the great degree of empowerment that human beings have enjoyed over the past century, most of us remain content to let the world take shape around us, to let the powerful and influential push society in whatever direction they desire.

Hence, while the simple life would help bring us out of the passivity induced by the consumerist lifestyle, the simple life is by no means simple to live. And so we drift.

How much to consume education?

Posted by

moses

@

15:44

•

economics,

education,

society,

United Kingdom

•

0

comments

![]()

Let's face it, adults as a group are pretty bad at giving advice to young people. For example, if young people aim low, adults tell them to aim higher and have more ambition; on the other hand, if young people aim high, adults tell them to be realistic and to pay their dues first. Basically, a lot of advice actually boils down to "do/don't do what I did" or "be/don't be like me".

Then there are those who assume that people think or should think they way they do, and this group certainly includes young people as well.

In times of great uncertainty, the advice and words of wisdom become especially loud and numerous, as everyone chimes in on what they think people should or will do. And I dare say that most of them haven't got a clue.

Now, on the Guardian's question of whether the tripling of tuition fees to £9,000 will inevitably turn students into consumers –this is a silly question and those who are happy with it are quite inevitably going to come up with silly answers. I mean, it implies that students haven't always been consumers. Does the price of a good determine whether you are a consumer? Or is there some kind of a consumer continuum? Shoppers at cheap Tesco are not as much consumers as shoppers at Waitrose?

Of course, this doesn't matter to those who wish to use the question as an excuse to air their self-righteous opinions and advice. In particular, I'm thinking of those who would take this opportunity to remind young people of the value of education, of which they are themselves naturally and keenly aware.

But instead of rushing to tell people what they should or will do, let's address the question carefully. Aside from the fact that it seems to be predicated on the strange idea that students aren't already consumers of education, there is a related question that we must first ask: What qualities can we objectively attach to consumers as a group? Certainly, there are examples of consumers behaving both rationally and irrationally. At times, they are able to make pretty good cost/benefit calculations and drive the market in a way that benefits them; at other times, they consume almost mindlessly. The diversity of consumer behaviour means we cannot assign any particular quality to consumers in their capacity as consumers and argue whether students will be more or less like them.

It also suggests that it is difficult, if not impossible, to predict how students will generally behave due to the fee increase, beyond invoking a basic economic maxim and saying that demand for higher education will almost certainly go down to some extent.

So there really isn't a good answer to the question of whether university students will become consumers, not even if we interpret it as one that is concerned with the value that future students will place on university education.

Is that a boring answer? Well, I think it certainly beats the millionth musing on how students don't value the education they are receiving enough.

It is often said that knowledge is power. Is it? Or does knowledge simply avail us to the means of power, if that?

There are criticisms to be made of the naive view that knowledge can automatically solve the world's ills, but we do not even have to venture there. In the first place, we should ask what kind of knowledge is regarded as power.

It stands to reason that not all kinds of knowledge can be associated with power. But aside from the fact that some knowledge is obviously of limited use, there's a particular kind that is foremost in the hierarchy of knowledge, being perhaps the only kind that is really recognised as empowering in the minds of many: Actionable knowledge.

In a way, this is apt when we consider the naive belief that knowledge is automatically empowering. Obviously, actionable knowledge is valuable because it allows us to take actions that would otherwise not have been possible or as effective without it. On the other hand, the notion that only actionable knowledge is empowering leads to the idea that only knowledge that is actionable is worth pursuing. That is why we hear rants, such as the one in New York Times recently, about the amount of time and money spent pursuing 'useless' knowledge.

Such complaints do have their points, but they often leave us with the distinct impression that people expect a lot from the knowledge they pursue. They expect it to pave the way to good jobs, to yield financial profit, to save time—in short, knowledge is expected to have tangible benefits, measured in terms that people are already familiar with and fully expect.

There are two criticisms that can be made. Firstly, such expectations are contrary to the nature of discovery. Whether the discovery is unprecedented or personal, whether the knowledge gained is completely new or already known to others, gaining knowledge entails learning something you didn't know before. It is therefore strange that we think we know what we can expect out of gaining some knowledge. While we can perhaps guess at or imagine its possible outcomes, the process of learning is likely to entail learning more than just actionable knowledge. In any particular body of knowledge learned, perhaps only a small part of it is actionable knowledge. Yet such 'wastage' is an unavoidable part of the learning process, a consequence of not knowing what exactly to expect, and this is especially true when engaging in cutting-edge research that seeks to break new ground.

This brings us to the second point, which is what the New York Times article seems to overlook when it rehashes old complaints about the academic ivory tower: A lot of the knowledge gained through research in institutes of higher learning is 'useless' because research is not an entirely predictable process. Important discoveries are often unexpected and made when pursuing lines of inquiry that might initially seem esoteric and of limited practical consequence. Even if a body knowledge seems to be full of information that is of little use outside of academia, the discourse it generates may have a cumulative effect that could be instrumental to making important discoveries within that body or outside of it. Thus, research is not made up self-contained projects that either yield useful results or not—research can be seen as consisting of discourses that together form the ground from which new knowledge germinates, not necessarily as a result of any single effort.

That is not to say that research need not be directed by practical goals. However, we should not be surprised that only "around 40 percent" or whatever proportion of academic research proves to be immediately useful in practical contexts. These circumstances are part and parcel of the process of research, and perhaps it is a gross misunderstanding of the way knowledge is gained that leads to the kind of cynicism that demands that knowledge yield tangible rewards or be deemed not worthwhile.